Suffering in the dark Manitoba collecting race-based COVID-19 infection data but hasn't made it public; critics say that leaves already-marginalized, minority populations at greater risk

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 13/11/2020 (1849 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

As jurisdictions across the globe report disproportionate impacts of COVID-19 on marginalized and minority populations, Manitobans remain in the dark about whether those trends are unfolding here.

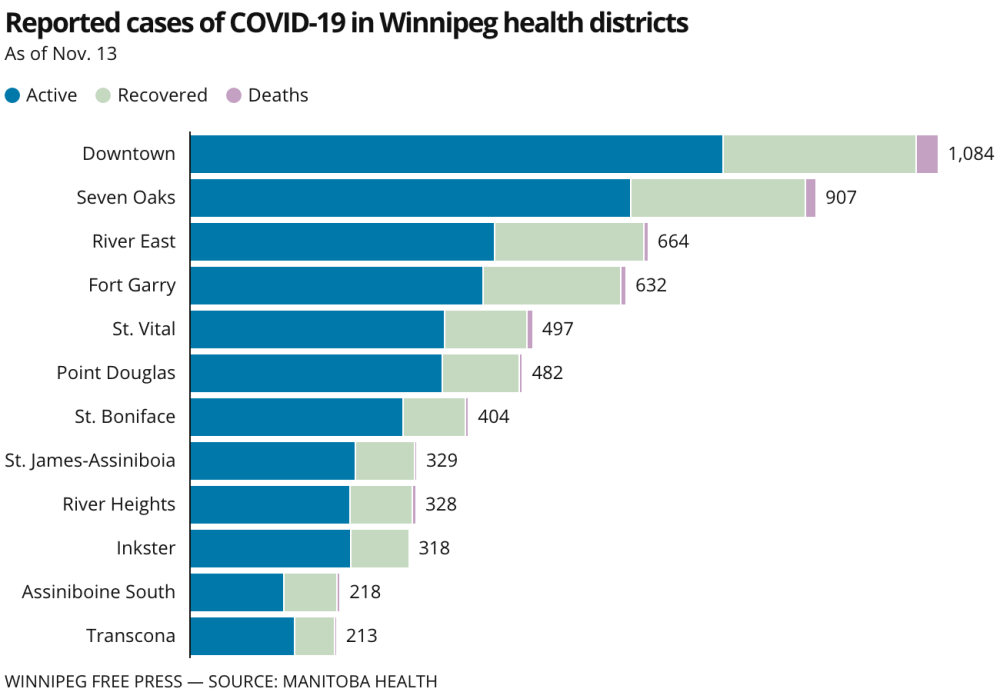

In Winnipeg, the downtown core and Seven Oaks have been hardest hit.

As of Thursday, 1,084 people had been infected with the virus downtown, including 771 active cases and 32 deaths. Just behind was Seven Oaks, with a total of 907 people infected, including 639 active cases and 16 deaths. More than 100 cases in each area were linked to outbreaks at nursing homes.

As case counts continue to climb and community transmission spirals further out of control, higher infection rates in those areas raise questions.

Dorota Blumczynska, executive director of the Immigrant and Refugee Community Organization of Manitoba, said the lack of public data on which populations are being hit hardest represents a “failure of public policy.”

“We know anecdotally that racialized Black and Indigenous people of colour, immigrants or non-status, they’re overexposed and overrepresented in every aspect of the ways in which our systems fail human beings,” she said.

Collection of race-based data, or the failure to do so, has been the subject of much discussion during the pandemic. Such data can show policy-makers and the public the disparate impacts health crises can have.

Early evidence from the United States has indicated the Black population has been disproportionately affected by the pandemic. In Chicago, for example, a study found that Black residents represented 72 per cent of COVID-19 deaths, despite making up only one-third of the city’s population.

In England, studies have shown Black and Asian Britons are dying in disproportionate numbers.

But without the robust collection and publication of data, it’s difficult to say whether the same thing is happening here.

In May, Manitoba became one of the first provinces to announce it would begin collecting race-based data related to COVID-19. But at the time, chief public health officer Dr. Brent Roussin wouldn’t commit to its release. Seven months later, Manitobans still do not have access to the data.

“We know anecdotally that racialized Black and Indigenous people of colour, immigrants or non-status, they’re overexposed and overrepresented in every aspect of the ways in which our systems fail human beings.” – Dorota Blumczynska, IRCOM’s executive director

The Free Press submitted multiple requests this week to the provincial government asking for an update on its collection of race-based data, including if and when it would be publicly released, but did not receive a response.

“The fact this pandemic started and no one within the health-care system said from Day 1 there should be something on this form that gathers race data, economic data, geographical data, immigration data, to the extent it is possible under the law, is appalling,” Blumczynska said.

In addition, Blumczynska said she feels the province has an obligation to publish socio-economic, gender and immigration data to whatever extent possible. She wasn’t surprised to see a concentration of cases in the downtown core, given the circumstances many residents live in.

“In the inner-city it is very difficult to get food. There’s a vacuum of fresh food and fresh produce. People often live in close quarters, often with multiple families in one household,” she said.

“But people also have to go to greater lengths, they have to travel further, they have to go to multiple locations, just to source basic staples and basic necessities. At every single corner, we’re increasing the exposure.”

Blumczynska also pointed to the economic realities many refugees and new immigrants face, including the sorts of jobs they are able to get, as factors that can increase their virus risk.

The only publicly available race-based data in the province comes from the Manitoba First Nations COVID-19 Pandemic Response Co-ordination Team, which has been publishing details on the impact of the virus.

As of Thursday, Indigenous peoples accounted for 35 per cent of all patients battling COVID-19 in intensive-care units in Manitoba, as well as 24 per cent of hospitalizations. Eighteen per cent of all people currently infected with the virus in Manitoba are Indigenous. Numerically it breaks down to 12 in ICU, 16 deaths, 54 in hospital and 1,086 total cases.

Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs Grand Chief Arlen Dumas said it has been important to collect data on how the virus impacts Indigenous peoples. He said that’s helped them better advocate for the communities they represent.

“Today, we’re at 35 per cent of ICU, but… yesterday we were at 45 per cent and last Thursday we were at almost 70 per cent,” he said Thursday.

“At the moment, our death rate is at 12 per cent, which is really unfortunate because we’re just under 10 per cent of the overall population…. But our ability to monitor and take a look at these numbers in a live way helps with our advocacy.”

Dumas said that because of the structural disadvantages Indigenous peoples face the statistics they’ve been tracking are “not surprising.”

Prior to becoming a chief, Dumas said he worked as a health director during the H1N1 pandemic of 2009, and the saw the ways in which health crises such as COVID-19 can devastate Indigenous communities.

And given where Manitoba is trending — with the highest infection rate in the country and a hospital system on the brink — he said the disproportionate impact on Indigenous peoples here is “quite concerning.”

“I think the proactive measures we’ve been taking is a testament to the fact we’re very attuned to the vulnerabilities of our population. We have an unfortunately very terrible history with these types of illnesses right back to the Spanish flu.” – Grand Chief Arlen Dumas

“I think the proactive measures we’ve been taking is a testament to the fact we’re very attuned to the vulnerabilities of our population. We have an unfortunately very terrible history with these types of illnesses right back to the Spanish flu,” he said.

“Because of socio-economic issues, systemic issues, housing shortages, it adds additional vulnerabilities to our populations…. It’s very alarming.”

Like Blumczynska, Dumas said he would like to see the province proactively publish data on traditionally marginalized, higher-risk populations.

“It’s incumbent upon the provincial government to be responsible and accountable and actually show the investments they make in Manitobans — in all Manitobans, regardless of which community they come from or which population they are,” he said.

“If they want to actually be transparent, then do so. Open the books so we can see. The province does have this information…. The facts and numbers don’t lie.”

Roussin was asked Thursday for his thoughts on the statistics published by the First Nations pandemic response team.

“It’s very concerning to see that disproportionate effect on Indigenous people and on First Nations. We knew in the first wave, just like we’ve seen with other pandemics… there can be a disproportionate effect in numbers of cases and in severity,” he said.

While official race-based data has been scant across the country — Toronto might be the lone exception, with monthly reporting of cases broken down by ethno-racial groups — a research team at Western University recently published findings that suggest patterns seen elsewhere are also happening in Canada.

The research team combined COVID-19 data from the Public Health Agency of Canada with census data that showed the racial and socio-economic breakdown of health regions in an effort to see if certain populations were being harder hit.

The findings showed higher infection rates in health regions with higher concentrations of Black and foreign-born residents. A one percentage point increase in Black residents within a health region doubled the COVID-19 infection rate, researchers said.

Likewise, data released from the municipal government in Toronto has shown Black residents significantly overrepresented among COVID-19 patients.

“These are system issues related to employment security, poverty, gender, that are creating conditions where people are making impossible decisions.” – Dorota Blumczynska

Some critics have pushed back against calls for the publication of race-based data, suggesting it could lead to further stigmatization of traditionally marginalized communities.

But Blumczynska said the benefits outweigh the potential harms.

“I understand that thought, but the stigmatization stems from racism. The reality is these communities are not voluntarily putting themselves at risk to fall ill or cause illness in their families. These are system issues related to employment security, poverty, gender, that are creating conditions where people are making impossible decisions,” she said.

“We can’t pretend this isn’t the case. We can’t say, ‘Let’s not reveal the data because there’s going to be a racist backlash.’ The racism is going to be there either way.”

ryan.thorpe@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @rk_thorpe

Ryan Thorpe likes the pace of daily news, the feeling of a broadsheet in his hands and the stress of never-ending deadlines hanging over his head.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, November 13, 2020 5:37 PM CST: Replaces sidebar with graphic