Remembering the Forgotten War Three Canadian veterans recall their experiences in the 1950s conflict that split Korea in two and never came to a formal end

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 07/11/2020 (1858 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It began with hundreds of thousands of North Korean troops crossing its southern border on June 25, 1950.

It ended… well, it has never really ended.

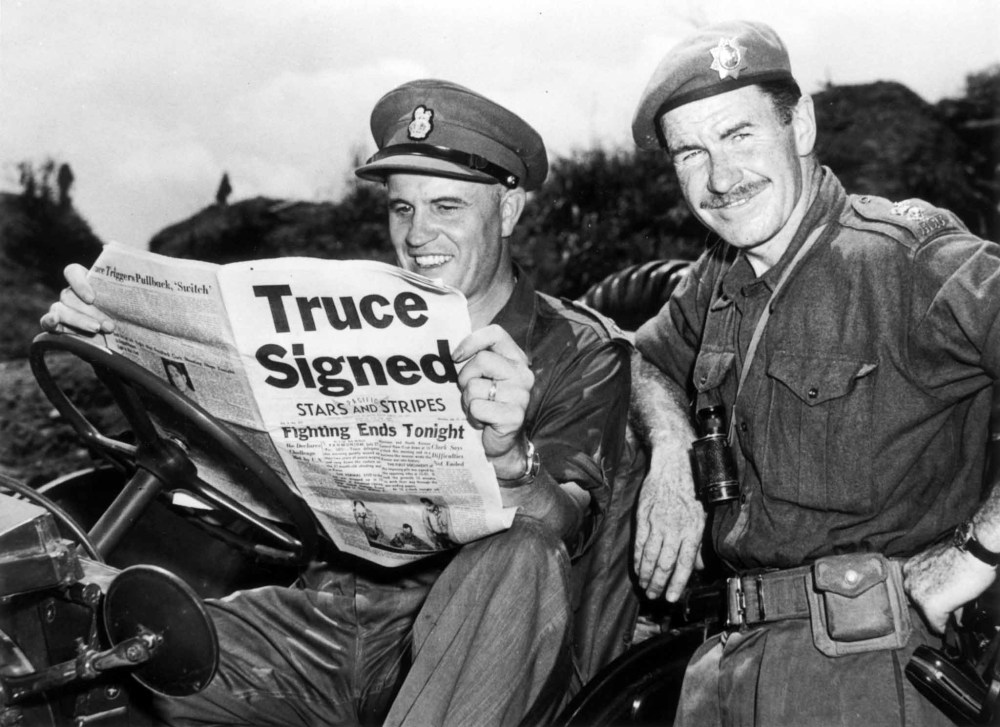

The Korean War began 70 years ago this year and, sure, there was an armistice on July 27, 1953, but there was no formal end to the war. It even took until 2018 for the leaders of the two sides, South Korean president Moon Jae-in and North Korean leader Kim-Jong Un, to sit at a summit and pledge to formally end the war.

But those talks fell apart and, earlier this year, soldiers fired shots at each other across the border. In recent years, North Korea has test fired long-range missiles.

The roots of the conflict started long before the first shots were fired 70 years ago.

Often referred to as the Forgotten War in the United States, where coverage was heavily censored, it was sandwiched between the end of the Second World War five years earlier and the start of the Vietnam War five years later.

The forces of 16 countries joined together under a United Nations Security Council motion to fight against the North Korean army and then the Chinese army. The United States never officially declared war — it has always referred to its presence as a police action.

Many people born in the 1960s and later know about the war only as the setting for both the 1970 film M*A*S*H and the TV series it inspired that ran from 1972 to 1983.

About three million people, including 36,000 American troops, were killed in the three-year conflict.

Canada sent 26,000 troops, losing 516.

It was a war in which Canadian soldiers were internationally recognized for their bravery during the Battle of Kapyong.

Jeong Min Kim, an associate professor in the history department at the University of Manitoba who specializes in modern Korean and East Asian history, said the effects of the war still ripple down through the decades, right up to the brief meeting between U.S. President Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un at the border separating the two Koreas.

“They made kind of a show in public, but I’m not very optimistic about it,” Kim said. “The show doesn’t usually end in a conflict resolution.”

As for whether the two nations could one day become one, Kim says it is possible, but it would take time and hard work.

“It would take a very long time for a unification,” she said.

“It would require a unified government… it is going to be a really large project to work on. I would not be entirely pessimistic about the possibility… but lots of things would have to be resolved first, like divided families.”

That’s because the of way the war didn’t just leave a permanent border. It split families, including children from parents, some of whom never again laid eyes on each other.

“My family is from South Korea and it didn’t leave a divided family with us,” Kim said. “But many of my friends do have that history. Before the Korean War, people could cross the border no problem. They didn’t believe it could become permanent. Some people thought they could go home in a few weeks and then they could never return.”

Kim said the seeds of the conflict were sown by colonialism years before.

After Japan fought in the Russo-Japanese War in 1904 and 1905, and defeated Imperial Russia, Japan turned Korea into its protectorate and then, in 1910, annexed it. It continued to rule the country through to the end of the Second World War.

The country was divided into two occupation zones at the 38th parallel at the end of the Second World War, with the Soviet Union administering the northern section and the United States the south.

Three years later, with the Cold War between the superpowers beginning, the two zones of occupation became countries, with the north headed by Kim Il-sung, the current leader’s grandfather, who ruled as premier and then president until 1994. Both the Soviet and American armies withdrew from the two Koreas.

It was Kim Il-sung who gave the green light to the invasion by the Korean People’s Army, with the United Nations Security Council responding by authorizing the creation of armed forces to fight back.

In total, 21 countries joined the United Nations’ effort, but the United States led the bulk of the response with almost 90 per cent of the combined armed forces. At first, the UN-led forces pushed back the North Korean army but, when it came close to the Chinese border, the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army entered the war, quickly gaining the upper hand.

The two sides went back and forth until there was a stalemate and an armistice was signed on July 27, 1953, creating a Demilitarized Zone to separate the two countries.

Sixty-seven years later, little has changed.

“The war isn’t officially ended yet,” Kim says.

“In South Korea it is called a war, but in every UN document it is called the Korean conflict. (U.S. president Harry) Truman said it was a police action.”

● ● ●

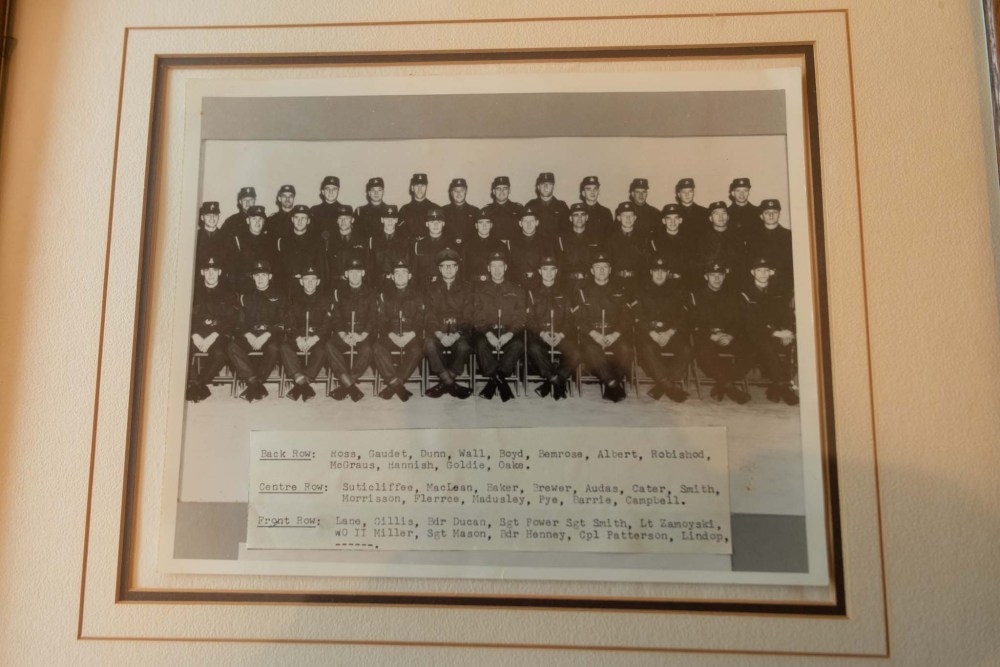

Just like there are two Koreas, you could almost say there were two Canadian armies that fought there. The first troops were a bunch of contracted volunteers known as the Special Service Force. The regular Canadian forces followed.

The Special Service Force was made up of a mix of veterans of the Second World War and Canadians who were out of work and saw the war as a way of gaining experience they could use to get a job once they returned home — and to make some money and get free food and accommodation.

Just two months after the war began, in August 1950 the Special Service Force became the 2nd Battalion of the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry.

It was this hastily put-together battalion that faced troops in the Chinese army at the Battle of Kapyong April 22-25, 1951.

After watching South Korean troops ahead of them suddenly retreating past them in the Kapyong Valley, Canadian troops were ordered to stop the Chinese forces. At one point, the battalion was completely surrounded by the enemy. Soldiers from both sides were so close together that the battalion’s officers had to radio its forces to fire artillery on its own position and received more ammunition and supplies only via parachute drops.

Sacrifice and service

Posted:

More than one million Canadians and Newfoundlanders served in the Second World War. More than 45,000 soldiers were killed and 55,000 wounded.

By April 25, the Chinese attack had been stopped, a road to the Canadian troops was retaken, and fresh soldiers replaced the ones who’d beaten back the enemy. It was a victory, but 10 Canadian soldiers were killed and 23 wounded. The battalion later received the U.S. Presidential Citation for its heroism.

A few months later, members of the battalion were on their way home and, in their place, regular troops with the Canadian forces were sent over for the remainder of the war and, afterwards, stayed as military observers for three years.

No matter which battalion Canadian soldiers fought in, seven decades after the conflict broke out — like the rapidly diminishing number of Second World War veterans — they, too, are disappearing. As of last year, the average age of Canada’s living Korean War veterans was 87 and, of the 26,000 that fought, there are now 6,500.

Three veterans living in Winnipeg recently talked to us about their wartime experiences in the Forgotten War.

● ● ●

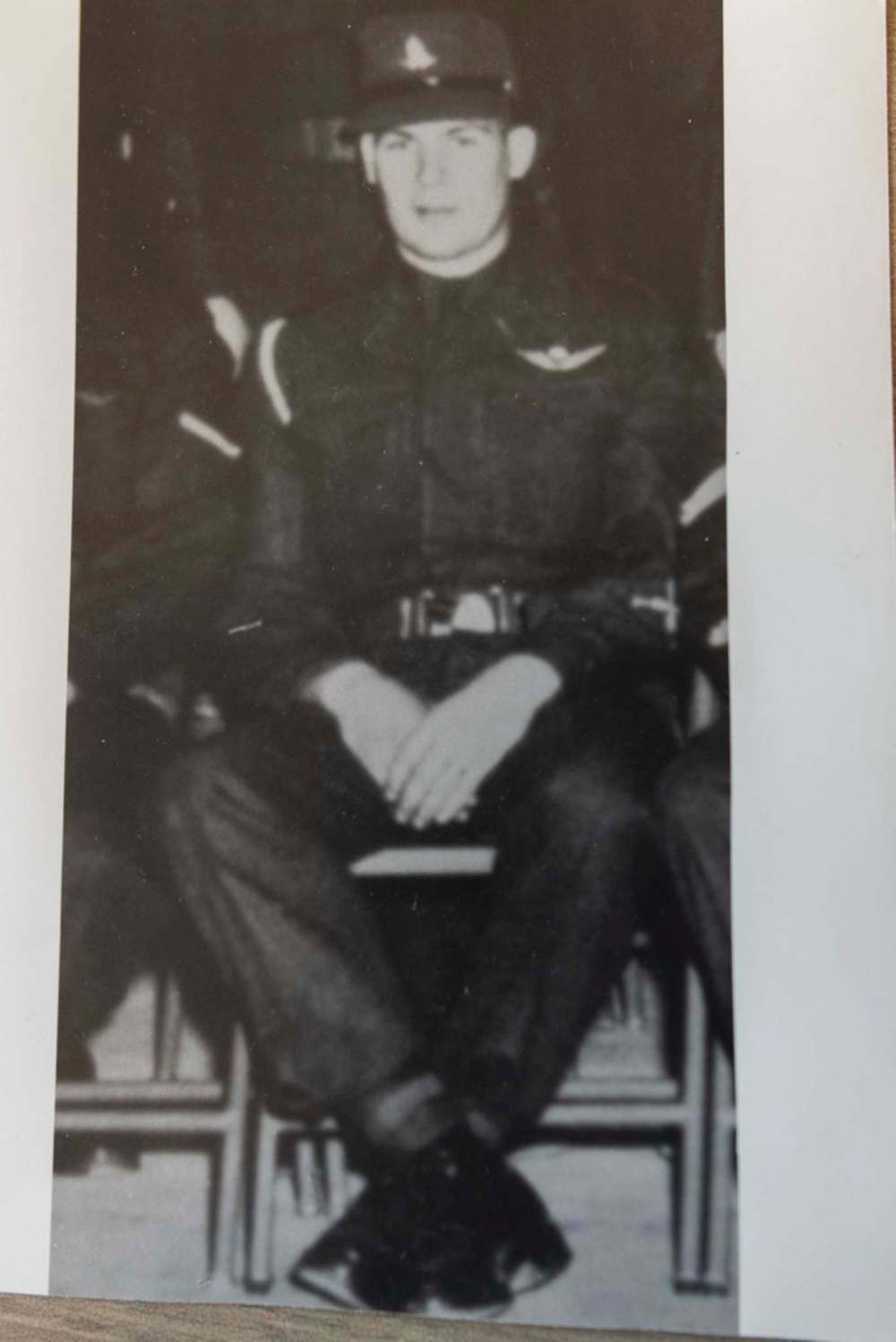

Michael Czuboka is 89 now; he was 18 when the Korean War broke out. And, just a few months after signing up and becoming a private, Czuboka was surrounded by enemy troops and fighting for his life at the Battle of Kapyong.

“It doesn’t feel like 70 years,” Czuboka says. “I had my 19th birthday there.

“One day you wake up and you’re old.”

Mind you, that birthday shows Czuboka shouldn’t even have been in Korea. Back then you had to be 19 to apply for the Special Service Force — he wouldn’t reach that age for a few months — but sign up he did. He says he didn’t lie by much, but he was “troubled” to fib, and he joined the more than 4,000 Canadians who enlisted in just two weeks.

Czuboka’s parents were Ukrainian immigrants, arriving years apart, then meeting and marrying in Canada. His father was interred in Canadian prison camps during the First World War.

Czuboka grew up in Rivers and helped support his family by selling vegetables from their garden and working in the local bakery.

“I had finished Grade 12 and I had no job,” he says. “I had no money to get to university… I thought it was just an adventure. I signed up.”

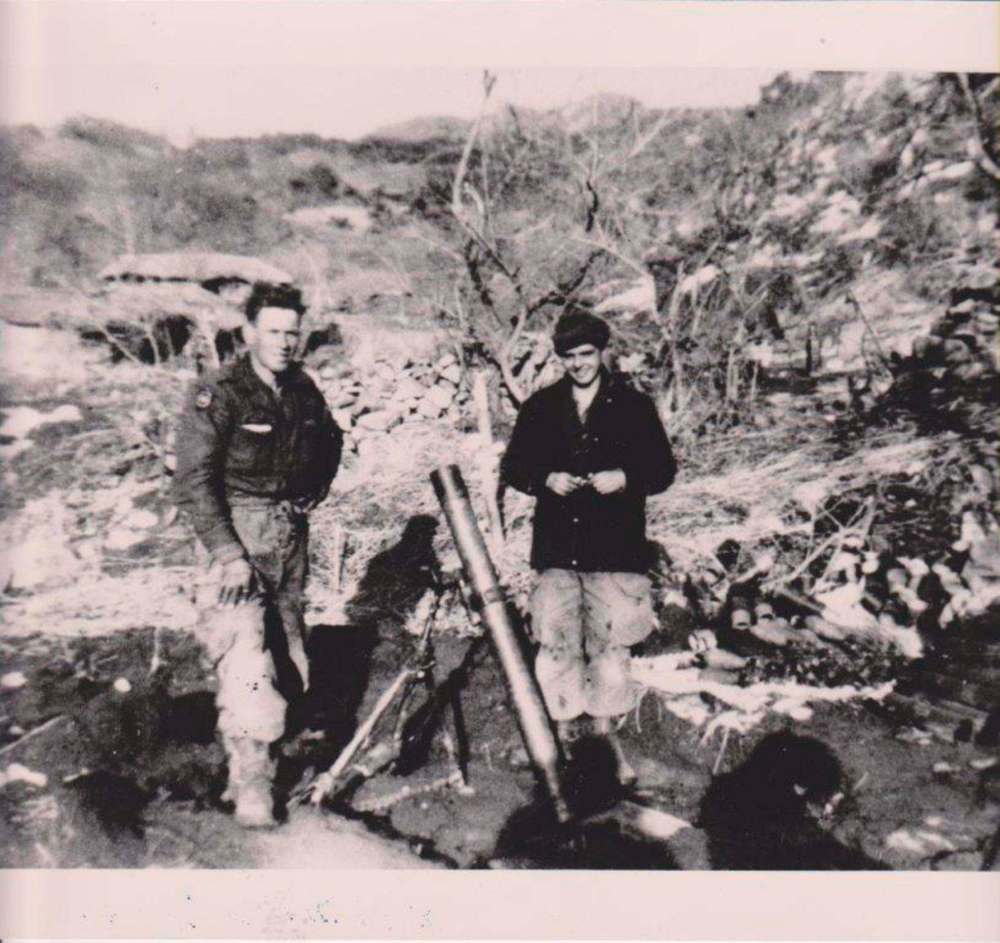

He ended up in the artillery and came back with permanent ear damage from feeding shells into the 81-millimetre mortar tube. He still hears buzzing and hissing sounds.

The Canadian forces who fought first in Korea were volunteers, unlike many of the soldiers from other countries they fought alongside.

.jpg?w=1000)

The Battle of Kapyong is vividly etched into his memory.

“We were surrounded for a couple of days,” he says. “When you’re in this situation you’re just there to survive.

“You’re firing your weapon to survive. The British lost a whole battalion and they were just a few miles to the west.

“We were very lucky.”

The Chinese soldiers were just 100 yards away.

“They were right up to us,” he says. “Other people were on machine guns. We were still firing the big guns, almost straight up.”

Czuboka estimates he helped send more than 1,000 mortar bombs onto the enemy while surrounded, helping prevent the rifle units from being overwhelmed.

He later spent a week being treated for dysentery at an American MASH in March 1951.

“I was delivered to the MASH by two tall, turbaned East Indians in a jeep with canvas stretchers,” he said. “Two wounded Chinese were in cots next to me and they screamed with pain all the way there. The Chinese were unarmed, but I kept my rifle ready just in case… the Americans, unlike the North Koreans, treated wounded prisoners in the same way as their own wounded.

“I was very ill with severe dysentery and my pants were soaked with a horrible liquid that partly froze in about -30C and ran uncontrollably down my legs.”

Czuboka, like many other veterans, blames the cold winter he lived through in Korea for he debilitating osteoarthritis he has now. He uses a walker to stabilize himself.

He served with the 2nd Battalion in 1950-51, and stayed with the army until 1954 when he went to Brandon College. He later became a high school teacher and principal before becoming superintendent of the Agassiz School Division until 1990. Besides being a past president of the Manitoba Association of School Superintendents, and a 16-year councillor for the Town of Beausejour, he is also the author of six books, including Juba, a biography of the former Winnipeg mayor, and Ukrainian Canadian, Eh?, a Canadian bestseller.

And Czuboka has been back to Korea three times over the years, his last visit in 2002.

“It is a modern country now — it was destroyed before,” he says. “Now it is more modern than Canada.”

A few months ago, Czuboka checked himself into a nursing home so that his wife, a critical care nurse at St. Boniface Hospital, didn’t have to worry about him while she was working.

He says the Korean War had many parallels with the First World War.

“We had trenches and barbed wire.”

The founding president of the Korean War Veterans’ Association in Manitoba says time has done what the enemy couldn’t all those years ago.

“There used to be 300 members would come out for a meeting two decades ago,” he says. “Now, only five still show up.”

● ● ●

John Gillis is 87 now and was part of the second wave of Canadian troops that went to Korea and replaced the 2nd Battalion.

“I wasn’t doing much so they created a war to keep us busy,” he says, laughing. “Employment was at a very low point in those days. People couldn’t get a job, that’s why I joined.

“We were so young we didn’t know much about communism. We just wanted a job.”

Gillis was a gunner in the artillery with the Royal Canadian Horse Artillery and trained at Camp Shilo. He worked as a radio operator who called in the targets.

“I was told that I was going to — because I was too young to go to Korea — I was going to go to the Winnipeg Flood,” he says.

“Later on, I guess they changed their mind, and a sergeant major told me (I was) going to Korea. And I said, ‘I’m not old enough,’ and he said, ‘You will be by the time you get there.’

“That was pretty well how it worked.”

A train collision delayed his deployment.

Gillis was being sent to Fort Lewis, in Washington state, for advanced training before being shipped to Korea. Tragically, Gillis and hundreds of others took that train trip twice. He was with 314 men and 23 officers on Nov. 21, 1950, when the train they were on collided head on with another, killing 17 soldiers and both two-person train crews. It was known as the Canoe River train crash and the troop cars were so damaged, rescuers described them at the time as “damaged beyond recognition.” Survivors were in frigid weather for hours until medical crews could arrive.

“I was asleep,” he says. “I woke up very quickly. I had a few stitches, but I was OK.”

Gillis says he ended up returning to Shilo until the soldiers again were transported to Fort Lewis. From there he boarded a ship for Korea in spring 1951.

Gillis said unlike the infantry, which fought on the front lines, the artillery was somewhat disconnected from the fray.

“They… give you a grid reference, and then tell you what to shoot at and you’d shoot at a grid reference,” he says. “You don’t really know, you’re in a vehicle with… radios and what have you and you don’t get to know… what you’re shooting at or why you’re shooting at it, or whatever.

“Find out a lot after, after you come back, than what you knew there, actually… we had 25 pounder guns and the enemy is 25 miles away.”

Gillis initially had enlisted for three years, but he ended up spending 27 years in the military, serving in NATO in Germany and taking part in two peacekeeping operations.

Afterwards, he became a writer, broadcaster and commentator with CJOB. He was also an active member of the Royal Canadian Legion for more than four decades, and was the MC for years at the downtown Remembrance Day ceremony, and has been honoured with numerous awards and medals, including the Queen’s Jubilee Medal, the Meritorious Service Medal and the Governor General’s Certificate of Appreciation.

Now, as Gillis has COPD and arthritis. He used to speak at schools, but is no longer able.

“There’s a lot more interest with the younger people now (about the military). It happened because of Afghanistan, where Canadians were dying once again. They take a lot more interest than they used to and they ask very good questions.

“But now, when I think about it, the war seems like a dream,” he says. “But not a good dream.”

● ● ●

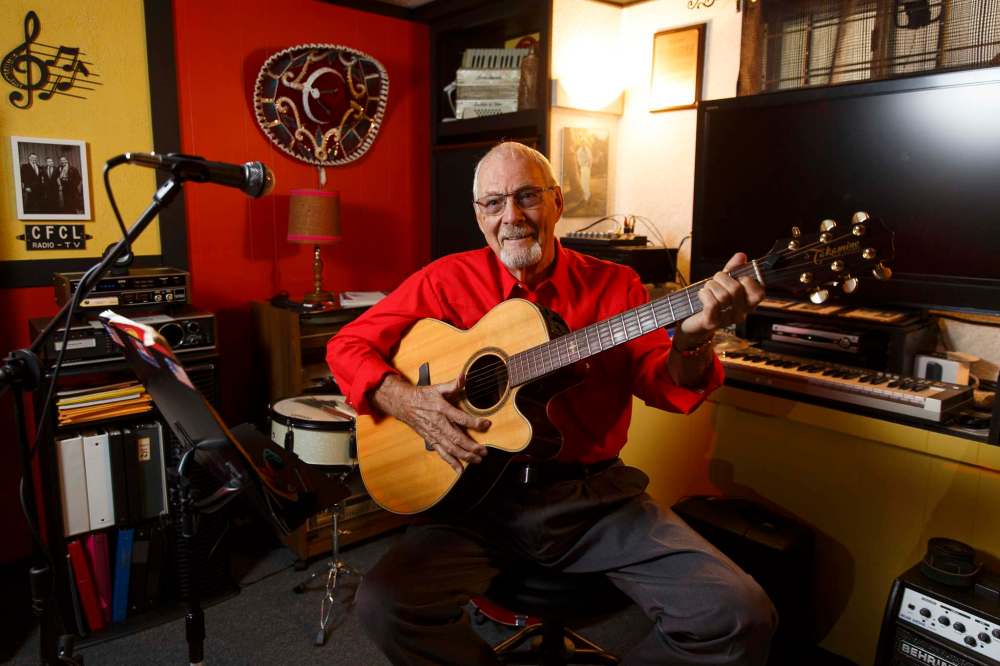

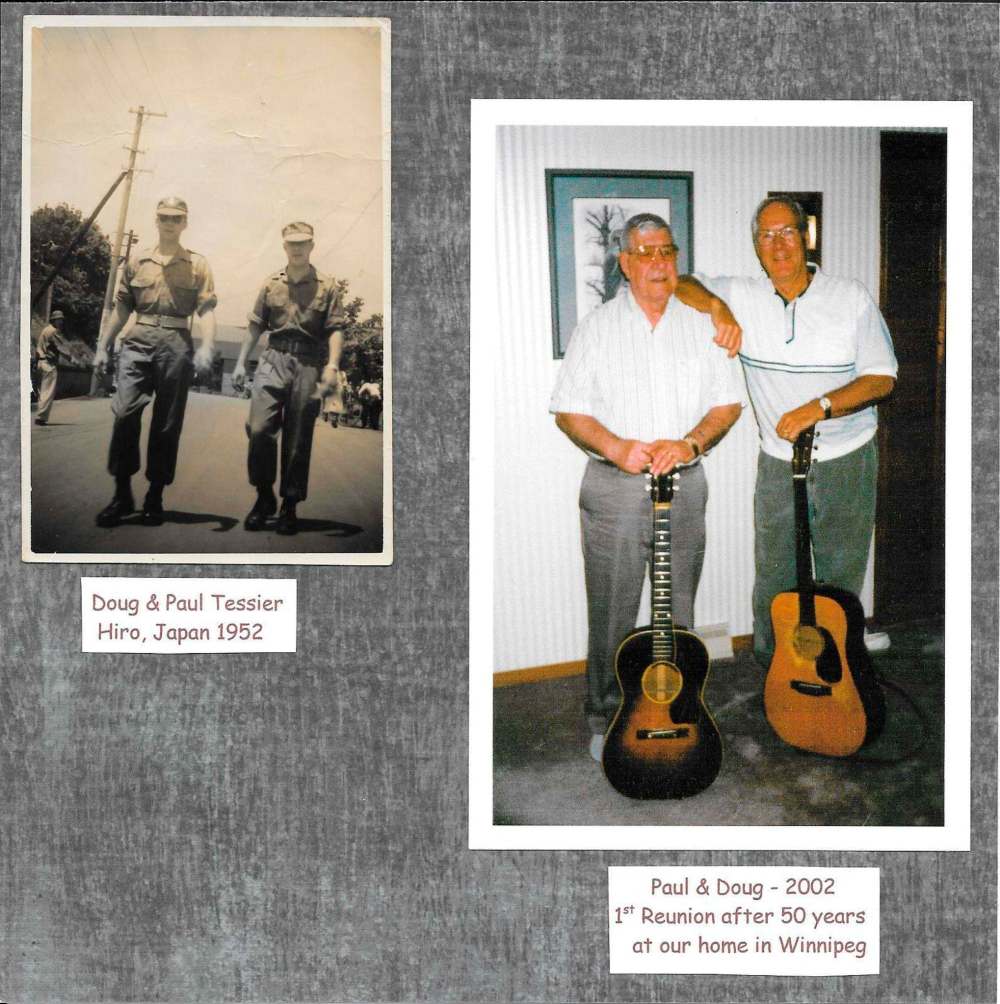

Doug Raynbird’s father served with the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry during the Second World War.

“He just looked at me one day and said, “You know, I think the military life for you would be good,” recalls Raynbird, who celebrated his 88th birthday recently.

“He actually talked me into it.”

Not only did his father talk him into the army, he also had to get him in.

“I was just 17 1/2 in July 1950,” he says. “My dad had to sign for me.”

A few months later, Raynbird was a member of the First Battalion of the PPCLI.

Raynbird and the rest of the battalion were shipped over to Korea and soon were on the front lines in the thick of combat.

“I was in the front lines for five days, that was it,” he says. “The first five days, I was digging a hole in the ground. We had gone to pick up our food in our mess tents. We came back — we had a hole dug four feet deep with logs over it — that was to be our base for the next year.”

Enemy troops were shelling the area, and he had just shown another soldier the knife on his belt — one issued by the U.S. Marines — before putting it back into its sheath.

“Two shells came in over top of us and behind us. I said ‘duck!’ and the knife came out and I fell on top of the knife. It went in just against the top of my hip bone. Half an inch higher and it would have gone right into my kidney. It went through two layers of webbing on my belt, my uniform and my underwear. If not for the knife, I wouldn’t have been wounded at the time.”

“They (enemy troops) could see us and they were shelling us as we went down the road. We just humped it to get off that road. It was about 200 yards.” – Doug Raynbird

Raynbird was so angry at his bad luck that he pulled the knife out of his body, said a “nasty word,” threw it as far as he could and told the other soldier, “I stabbed myself.”

“My hand was all covered with blood. We crawled out and started down the hill.”

The knife wasn’t the problem any longer.

“They (enemy troops) could see us and they were shelling us as we went down the road. We just humped it to get off that road. It was about 200 yards,” he says. “Believe me, I was moving fast.”

He was treated at a military hospital in Incheon and then flown to a British hospital in Japan.

While recovering there, a soldier he’d met while they were training at Camp Borden in Ontario, paid him a visit.

The soldier had also been wounded and, after recovering, had begun participating in an army variety show. Two weeks later, Raynbird met the officer in charge of the show — Lt. Gordon Atkinson, who later joined CBC and, at one point, was program director at CBC Winnipeg.

“I said I’d done a little country singing, I said I could yodel a little bit. I also sang on CJOB and won the King of the Saddle contest. He said, ‘We can use you.’”

Raynbird said he performed in the variety show for a two-week tour in bases in Japan, followed by two more tours of duty in different shows over the next 10 months.

“We set up a stage right at the front lines. We made our own stage with oil drums and planks. Wayne and Shuster later used the stage we built.”

He went on to have a successful career in television and radio, performing on Red River Barn Dance and Red River Jamboree.

“Not too many people know this, but when you sign up for the permanent force, you are never discharged,” he says. “You are subject to recall at any time, but I don’t think they’d want me now.”

Raynbird and his wife went back to Korea a few years ago.

“It’s amazing how the Korean people treat you,” he says. “People bow to you. They have never forgotten. It was almost embarrassing.”

● ● ●

“I don’t think (the war) was really ‘forgotten,’” Czuboka says. “I think that’s inaccurate. It’s really appreciated by the Korean people. We saved them from a dictatorship.”

Gillis says “everyone calls it the Forgotten War, but we were the ones trying to forget.”

And Raynbird says that some people refer to it that way, but “But not by the people who were there.”

kevin.rollason@freepress.mb.ca

Kevin Rollason is one of the more versatile reporters at the Winnipeg Free Press. Whether it is covering city hall, the law courts, or general reporting, Rollason can be counted on to not only answer the 5 Ws — Who, What, When, Where and Why — but to do it in an interesting and accessible way for readers.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.