Failure to act Manitoba COVID woes can be traced to government's 'incompetent reaction': experts

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 30/10/2020 (1865 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The excitement was palpable when Premier Brian Pallister, in mid-July, announced Manitobans had listened and learned during the pandemic lockdown. Now, it was time to reopen; it was time for business.

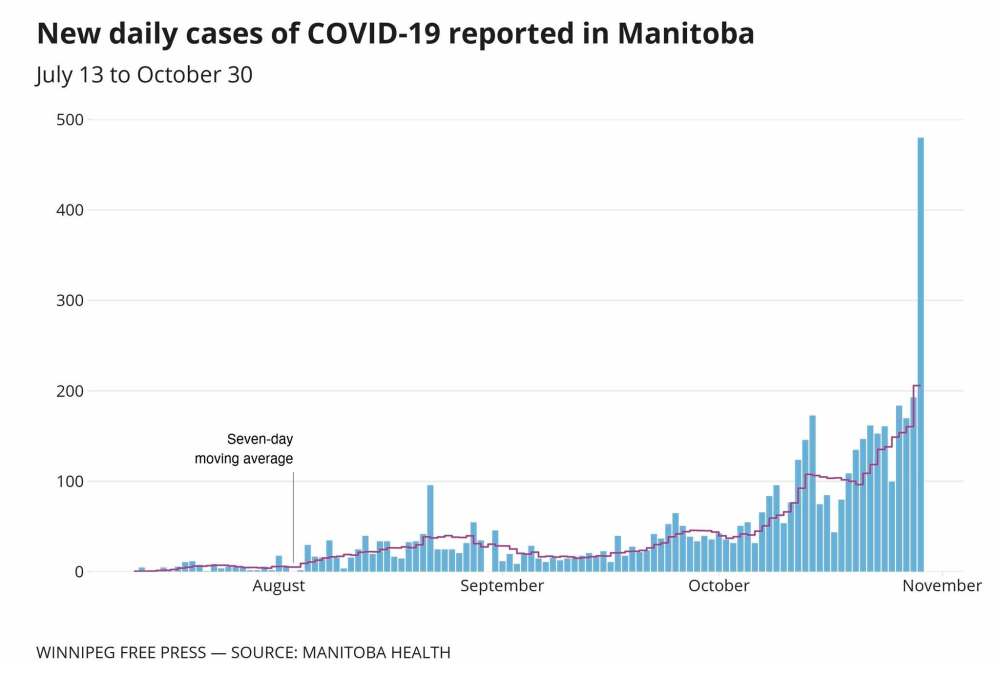

On July 13, Manitoba had one active case of the novel coronavirus, and it had been 13 consecutive days of no new cases. There had been fewer than 10 deaths, and the total case count was lower than in any other province in Canada.

Fast-forward 109 days.

Not only does Manitoba have the worst case count per capita in the country, but its largest city is on the verge of a shutdown. Fires have sparked: outbreaks in hospitals and personal care homes, critical care resources on the brink, and record numbers of positive cases on a near-daily basis.

On Friday, Manitoba announced 480 more people had been infected with COVID-19. The virus has claimed 65 lives, with most being residents of personal care homes.

Beginning Monday, the provincial capital is being downgraded to “red” on Manitoba’s pandemic response system; tighter restrictions are coming into effect.

What happened during those 109 days, according to multiple public health experts interviewed by the Free Press, is built on government hubris, ambivalence and failure to act responsibly with the interest of all Manitobans in mind.

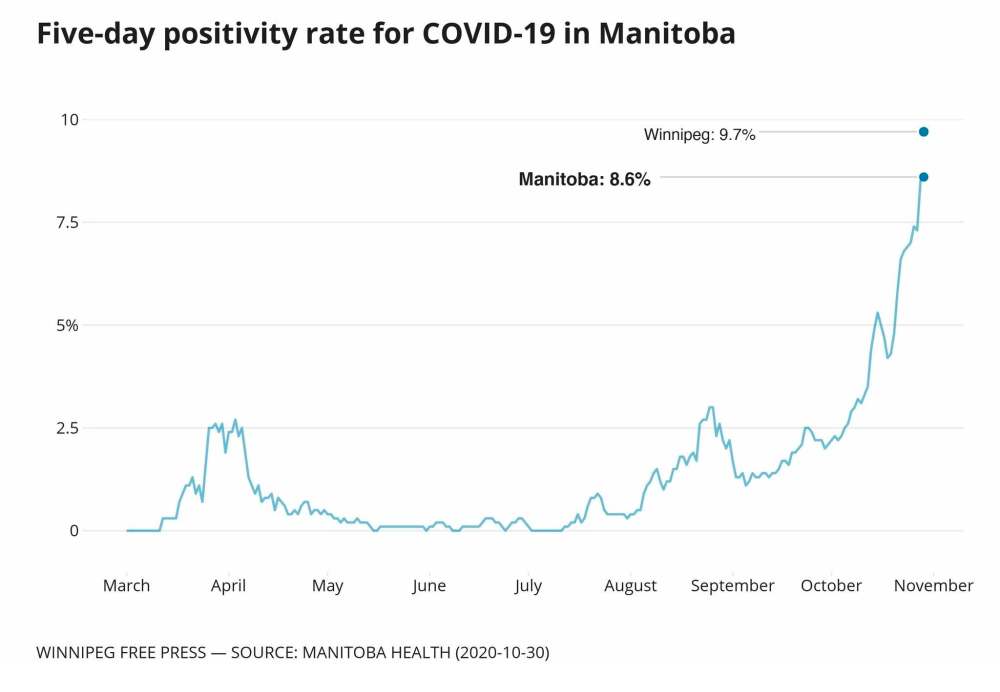

Community spread of the virus is high, the test-positivity rate in Winnipeg sits at 9.7 per cent, and the hospital system— according to a dozen doctors who have come forward publicly to sound the alarm — is on the verge of being overwhelmed.

During a news conference Friday, Dr. Brent Roussin, Manitoba chief provincial public health officer, was asked point-blank how the province had failed so badly. In response, he pivoted, saying: “We’re going to get through this.”

“We’ve seen, certainly, a lot more cases than we wanted to. There is no surprise with this virus. It’s being transmitted exactly the way we thought it would and the manner in which we thought it would,” Roussin said.

“We’ve seen, certainly, a lot more cases than we wanted to. There is no surprise with this virus. It’s being transmitted exactly the way we thought it would and the manner in which we thought it would.”

– Dr. Brent Roussin

The response raised an important question: if the virus is spreading as government officials knew it would, how did we end up here?

Dr. Amir Attaran, a professor of public health at the University of Ottawa, said the provincial government has seriously mismanaged its response to the pandemic. As a result, he said Manitobans needs to brace themselves for an “extreme crisis” in the coming weeks.

“This sounds like the most incompetent reaction I’ve seen in Canada since the pandemic started… When you’ve got a test-positivity rate nearing 10 per cent, you’re on par with some of the worst places in (President) Donald Trump’s United States,” Attaran said.

New restrictions not enough: ICU doctor

Posted:

The author of an open letter signed by 11 doctors, arguing government should shut down the province before COVID-19 numbers overwhelm the medical system, doesn’t think Manitoba went far enough Friday.

Attaran argues while there are many “scientific unknowns” about the novel coronavirus, it’s well-known what must be done to mitigate worst-possible outcomes: enforce social distancing and the wearing of face masks, limit mass indoor gatherings, shut down the riskiest potential sites of transmission, and implement severe restrictions at venues allowed to remain open.

That Manitoba now finds itself in the situation it does, Attaran said, indicates the provincial government failed to act.

He further claims Manitoba ignored important warning signs, such as a growing test-positivity rate in Winnipeg. The tighter restrictions announced by the province Friday may be too little, too late.

“It will require measures very much harder than even what was on the table at the end of March and beginning of April. You’re starting from a much higher place right now. You’ve got hundreds of cases per day. You’re now an order of magnitude higher,” Attaran said.

“The higher you climb the mountain, the longer it takes to get down the other side. And Manitoba has climbed an awfully big mountain right now… Test-positivity is nearly 10 per cent. That is just, wow, I don’t have words for that.”

On Friday, Lanette Siragusa, chief provincial nursing officer, said Winnipeg hospitals will start moving less-sick patients without COVID-19 into home care or other buildings, to ease the anticipated strain on the system. She said staffing levels will be a concern moving forward.

For months, advocates have been pushing the provincial government to do more to improve its surge capacity, including the Manitoba Nurses Union.

In April, Shared Health and regional authorities established a provincial recruitment and redeployment team, which started by assigning the medical staff freed-up when surgeries were postponed to pandemic-related work.

The province quietly launched a recruitment campaign over the summer, taking in 320 employees for everything from contact tracing and testing sites to screening care home visitors. Yet, it wasn’t until Oct. 19, as high community spread had officials restrict gatherings in Winnipeg, that Manitoba stepped up recruitment efforts and advertised postings for medical staff.

“The Pallister government basically had all summer to really get out there and start recruiting nurses and deal with retention issues.”

– Darlene Jackson, MNU president

“The Pallister government basically had all summer to really get out there and start recruiting nurses and deal with retention issues,” said Darlene Jackson, MNU president, adding nurses who have applied in recent months faced weeks of administrative delays in trying to get to the front line, even after undertaking training to update their credentials.

Dr. David Fisman, an epidemiologist, practicing physician in Toronto, and professor at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, said the success Manitoba had this summer in clamping down on the spread of the virus in the Prairie Mountain Health region may have lulled it into a false sense of security.

On Aug. 24, in the midst of rising case counts in Brandon, which included an outbreak at a Maple Leaf slaughterhouse, as well as clusters of cases on Hutterite colonies, the province downgraded Prairie Mountain to “orange” on the pandemic response system. By early September, daily case counts were down to single digits, and the tighter restrictions were soon lifted.

“I think Manitoba may have been led a bit astray by the success in Prairie Mountain in the summer, where a light touch with masking orders did seem to be enough to bring things under control. Winnipeg seems to be a different story,” Fisman said.

Comments from Dr. Anne Huang, a former deputy medical officer in Saskatchewan, and Dr. Nathan Stall, a member of the University of Toronto’s division of medicine, were of a similar vein, saying, respectively, the situation in Manitoba was “frightening” and “alarming.”

“This may be the most dramatic rise that we have witnessed in Canada to date; that’s my sense, given how fast it’s rising,” Huang said.

“We have witnessed (this) elsewhere in the world, for example Italy or initially in Wuhan (China), but it’s not something Canadians have seen much, other than perhaps in the long-term care setting in Ontario and Quebec… There must have been some gaps in the (Manitoba) defence system.”

Jack Lindsay, chair of emergency studies at Brandon University, said there are serious questions about how well Manitoba prepared for a second wave.

Ahead of anticipated flooding events, Lindsay said, the Medical Transportation Co-ordination Centre in Brandon often hires his undergraduate students. They are then trained to help rural Manitoba paramedics navigate closed or flooded roads, which means there is extra staff ready to deploy, even if floods are less severe than forecasted.

“We have witnessed (this) elsewhere in the world, for example Italy or initially in Wuhan (China), but it’s not something Canadians have seen much, other than perhaps in the long-term care setting in Ontario and Quebec… There must have been some gaps in the (Manitoba) defence system.”

– Dr. Anne Huang

It appears the province took no similar effort for contact tracing.

Unlike other provinces, Manitoba job postings require a year of medical experience, even for making rote follow-up calls. The province cannot say if any of the 1,153 Manitobans who volunteered this spring to help with contact tracing were ever hired.

During floods, the provincial government establishes an incident command centre to co-ordinate its response.

Manitoba established such a COVID-19 command centre in February, according to a statement sent June 30 to the Free Press. However, as Manitoba “pursued a reopening strategy,” it was deactivated. The province said if case counts spiked in the future, “the incident command structure would be reactivated.”

On Friday, the provincial government did not respond, by deadline, to a request for comment on if the COVID-19 incident command centre had been reactivated — and if so, when.

Told Manitoba had shut down its incident command centre in the midst of the pandemic, Attaran responded succinctly: “It’s stunning.”

— with files from Dylan Robertson

ryan.thorpe@freepress.mb.ca

Ryan Thorpe likes the pace of daily news, the feeling of a broadsheet in his hands and the stress of never-ending deadlines hanging over his head.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.