Lessons learned as leaves turn Health experts continue to unravel COVID-19 mystery as autumn chill sends social distancing-weary Canadians indoors

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 03/10/2020 (1895 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

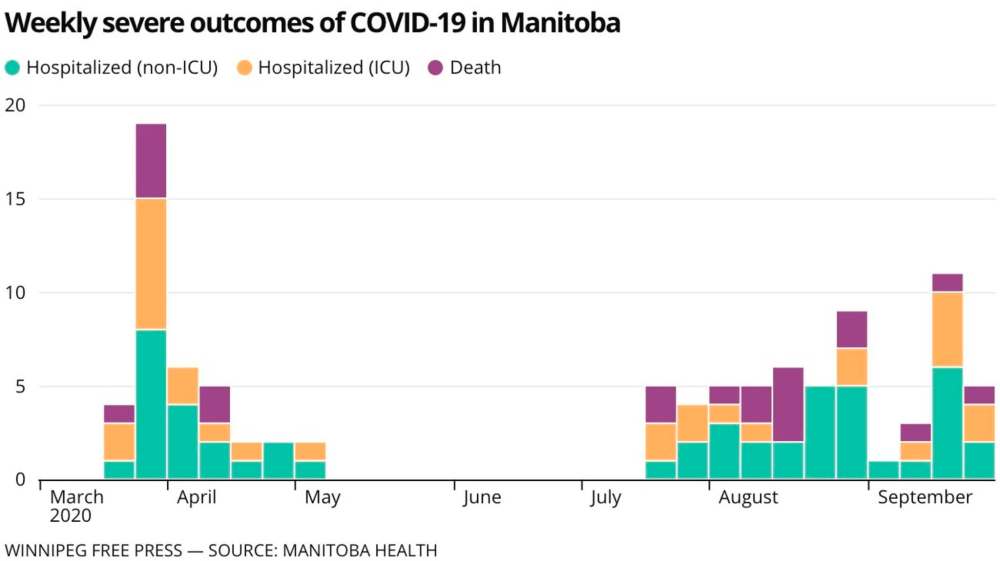

Of the more than one million COVID-19 deaths worldwide, about 9,200 have occurred in Canada.

Sadly, there will be more in the coming weeks.

Manitoba’s capital region is in code orange, and Montreal this week shut down restaurants and banned private gatherings.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has said most Thanksgiving gatherings can’t go ahead this year. Doctors worry that the approaching flu season will clog ICU wards and COVID-19 testing centres.

Unless Canadians cut down person-to-person contact, hospital capacity will be strained across the country, chief public health officer Theresa Tam says.

“The time is now; we’re at a bit of a crossroads,” she said on Sept. 22. “The challenge we face now is to stay the course, no matter how weary we may feel.”

But there is hope. Seven months ago, Canadians were wiping down their groceries, debating the merits of face masks and hoarding toilet paper.

“In March, when this first hit, what we didn’t know could fill books, and it was terrifying,” said Colin Furness, an epidemiologist and information-management professor at the University of Toronto.

“Since then, we have learned a lot around COVID: how it spreads, how it doesn’t spread, what it does to the body and how to treat it.”

The Free Press surveyed experts from across Canada on what we’ve learned from evolving research, to help Winnipeggers get through the fall and winter.

As Dr. Tam says, Canada can stilshl flatten the curve.

“We know what works, and we know we can work together to get this done,” she says.

Wear a mask indoors — and do it properly

Scientists have known for months COVID-19 is transmitted through respiratory droplets. Mouths and noses release these small particles, which generally fall to the floor within two metres.

It’s easy to inhale someone’s droplets. If they’re carrying the coronavirus, the pathogen enters your lungs, where it’s prepared to wreak havoc.

When two people wear masks, the number of droplets they exchange is drastically cut down.

“For sure, your greatest risk, outside of the health system, is a face-to-face conversation (without a mask) of 15 minutes or more, within two metres,” says Cynthia Carr, a Winnipeg epidemiologist.

Outdoors, the droplets dissipate into the open air, are blown away or have virus particles deactivated by sunlight.

That’s why outdoor activities are so much safer.

Very few infections have been traced to racial-justice protests during the summer. A panting jogger who passes someone on the sidewalk could be expelling viral particles, but Furness said it’s nearly impossible for a passerby to catch COVID-19 from them.

Meanwhile, almost every super-spreader event has occurred in enclosed spaces.

Singing and yelling propel droplets farther than simply speaking, which helps explain outbreaks in church choirs and karaoke bars.

“Being in situations where air is being circulated, instead of ventilated, is a key risk factor,” says Carr, whose firm EPI Research Inc. helps First Nations prevent and identify diseases.

When the pandemic reached Canada in March, public-health experts were hesitant to recommend cloth masks. Many suspected this was to prevent the hoarding of professional medical masks, but officials insist they didn’t want the public putting their energy into practices that might not be effective.

Initially, some felt that masks can give a false sense of security, encouraging people to get dangerously close, especially if the masks aren’t worn correctly. And officials still say it’s dangerous to be touching the front of a mask without washing your hands right after.

Yet since May, experts have encouraged people to wear cloth masks when indoors, or in any situation where it’s hard to keep two metres apart. The masks reduce the number of virus particles a person expels.

Officials continue to ask the public not to use professional medical masks, such as N-95 respirators. Those masks prevent inhalation of particles, but only when properly worn, and used by medical professionals in high-risk jobs.

A cloth mask works only when it covers your nose and mouth and, ideally, chin, experts say.

“You’ve got to wear the mask properly. If schoolchildren are learning how to do it, the rest of us can do it as well,” says Maureen Taylor, a physician assistant who specializes in infectious diseases at Michael Garron Hospital in Toronto.

“It’s a virus that is transmitted by breathing it in, and that’s why masks work pretty well.”

Meanwhile, microscopic particles on hands can enter the body after touching your eyes, nose or mouth.

The good news is that the coronavirus is covered by a fat-like structure that just about any soap will break up when washing your hands, including under fingernails and the back of one’s thumbs. Hand sanitizer is effective, but to a lesser extent.

Without the fat structure, the genetic code can no longer take host in living cells, and eventually breaks up on its own.

Finally, limiting one’s contacts with others means a much lower risk of transmission.

Ontario officials initially suggested people form “bubbles” of no more than 10 contacts to gather in enclosed spaces; for the most part that meant mostly families, close friends and dating partners.

However, contact tracers say many people have instead formed chains of interlocking bubbles. That defeats the purpose of trying to limit contacts, says Dr. Anna Banerji, one of the faculty heads at the University of Toronto’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health.

“The bubbling phenomena only works if it’s a small group of people and it’s exclusive,” she said. “It has to be a closed circuit.”

Your groceries probably won’t infect you

Early in the pandemic, studies in temperature-controlled labs found the virus can live on metal surfaces for up to three days, and approximately a day on cardboard.

However, newer research suggests viruses sitting on those surfaces are a lot less infectious than originally thought.

U.S. infectious disease specialist Dr. Anthony Fauci says he leaves his groceries on a shelf and washes his hands, letting the food sit for a day (presumably on a kitchen counter and a clear fridge shelf).

Taylor says she avoids frequently touched surfaces, such as on public transit, but focuses her energy on masks and distancing.

“If I can use my shirt sleeve to open a door, I will — and if I can’t then I’ll wash my hands as soon as I can. But I’m not obsessing over that kind of thing anymore,” she says.

Carr said there are no widely known, documented cases of the virus spreading via touching things at the supermarket.

That doesn’t mean it’s not happening — about a fifth of current COVID-19 infections in Manitoba could not be traced to a specific person, which in theory, could include getting the virus from groceries, Carr says.

“Would I wash my groceries now? I would leave that up to the average person, but I would focus more on the other things that we know about,” Carr says pointing to avoiding close, indoor contacts.

The virus has many symptoms, but it’s rarely deadly

Most patients are infectious two days before their symptoms appear, and 10 days after that point, Taylor says.

The coronavirus presents with numerous symptoms; one of the few distinctive indicators is a diminished sense of smell and taste.

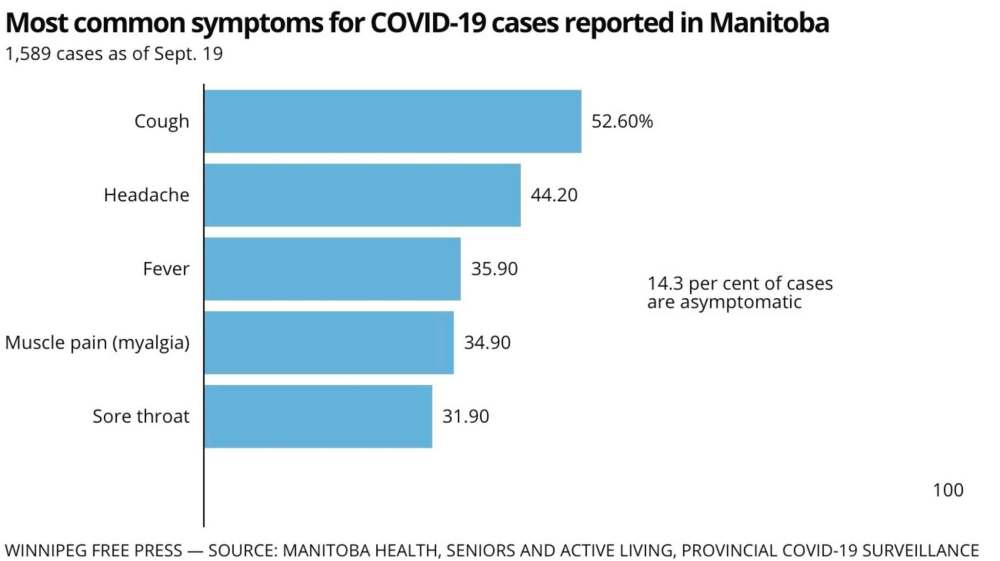

A dry cough and shortness of breath are among the most common symptoms, as is fever and, sometimes, headaches. In rare cases, there is a runny nose.

“Often this is something that comes out of the blue. At first you feel a little unwell; you might have a sore throat, you might have a mild cough. But in the second week you might get short of breath,” says Taylor.

“It’s about your third week when you’re so unwell and gasping for air that you finally come to the emergency department and get admitted to hospital.”

Even diarrhea and rashes have been linked to the coronavirus, says Banerji.

“COVID is the new great imitator,” she says. “It can present as any symptom.”

Healthy people can get COVID-19 and pass it along without even noticing — perhaps as a result of contracting a smaller dose of the virus.

Since the start of the pandemic, experts have known that immunocompromised people and those over 70 years old are most at risk at dying from COVID-19.

People with chronic conditions such as diabetes, high blood pressure and obesity tend to mount a weaker immune response to the disease. And the body can sometimes go into overdrive, attacking internal systems and creating a domino effect of organ failure.

In August, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention revealed 94 per cent of people who died from COVID-19 had other, pre-existing and often chronic conditions.

“The majority of people who are healthy are not at high risk of dying of COVID,” Banerji says. “Before we knew much about COVID we thought there’d be mass-casualty among the general population.”

In Canada, about six per cent of COVID-19 cases have resulted in deaths. That falls in line with Western European countries, though the death rate is always contingent on the number of people who’ve been tested.

We don’t know how much the virus mutates

The novel coronavirus is a round particle that contains genetic material known as RNA. The outer spikes of the virus latch onto cells, injecting the RNA, which contains instructions on how to turn more of the host’s cells into virus-making factories.

The immune system responds by deploying cells to kill the pathogen. That’s normally when symptoms appear.

Fever is a common response to many viruses, as the immune system raises the body’s temperature in an effort to cook a pathogen. Inflammation and pneumonia, caused by fluid on the lungs, are other byproducts of the body’s attempts to tackle an infection.

Since COVID-19 emerged late last year, both the RNA and the spike proteins have changed slightly. Mutations emerge when cells copy the virus, and some of these changes have become more prominent in certain regions of the world.

“What we do know so far is that this virus is not acting like any of the other coronaviruses before”– Cynthia Carr, Winnipeg epidemiologist who runs EPI Research Inc.

Tom Koch, a medical geographer at the University of British Columbia, says the strains in Canada suggest COVID-19 entered B.C. and Quebec from China through the United States — but that wasn’t the main source.

“A lot of the real growth of this pandemic in North America really came from the infection being introduced from Europe, and we know this because it’s a slightly different genome,” he says.

“We were looking towards China and it was coming through the back door.”

Initial studies suggest some of these strains vary in their ability to spread, such as by having spikes that more easily latch onto cells.

Quebec’s top doctor claimed in late September that the province’s higher mortality rate is due to a more-lethal strain of the virus than has been experienced elsewhere.

Other researchers, however, say the same strain is circulating in the rest of Canada and it does not seem particularly lethal, though it might be more easily transmittable than other variants.

Scientists are studying whether mutations will have implications on the effectiveness of vaccines currently undergoing testing; they want to know whether one vaccine will work against multiple types of the virus.

“What we do know so far is that this virus is not acting like any of the other coronaviruses before,” Carr says.

The two main coronaviruses that appeared before COVID-19 had less documented mutation.

The SARS virus that plagued Toronto and Hong Kong hospitals disappeared by the time a potential vaccine was ready for testing in 2004. The MERS virus has infected only about 2,500 people in the Middle East and South Korea since 2012, and is much more difficult to transmit than COVID-19.

Some researchers believe those two viruses haven’t mutated to the same extent because they haven’t passed through nearly as many people.

We don’t know how this impacts kids

Initial studies suggest children, particularly those under the age of 10, don’t contract or spread COVID-19 as easily as adults do. That has left researchers perplexed, given how easily children spread colds and flu.

One study in Iceland found that while parents tended to transmit COVID-19 to their children, there didn’t seem to be transmissions going the other way.

European countries resumed classes a few weeks earlier than Canadian provinces, and school outbreaks so far appear to be rare, though there have been some large, isolated flare-ups.

Belgian authorities have pondered whether schools actually help enforce kids distancing from each other, rather than hanging out between online classes.

A popular hypothesis is that children have underdeveloped genetic receptors known as ACE-2, the part of cells that COVID-19 attaches to, and so they contract the virus less easily.

Another is that children are, generally, shorter than adults, so their droplets spend less time in the air.

However, children are also showing up in ERs with undetected hypoxia — low blood-oxygen levels — and tissue damage despite being asymptomatic.

Furness says this appears somewhat similar to carbon-monoxide poisoning, in that the body isn’t sending signals such as shortness of breath despite being deprived of oxygen.

Experts such as Banerji warn that there have been few studies on how children contract or spread the disease, and that it’s unclear how reliable children’s swab tests are.

“I think it’s better to be cautious, rather than saying, ‘Well, kids don’t spread it,’” she says.

“We’re not going to get this under control in schools until most people are infected, or we get a vaccine.”

Taylor notes that contacts with children have been linked to influenza spreading in retirement homes in past years, and her top worry is school outbreaks indirectly resulting in elderly people getting very sick.

“Who are your children seeing on weekends and after school? If you do have grandparents in your life, I think you do have to start thinking about isolating from them for the next little while, until we get this back under better control, or do distancing outside,” she says.

“We really have to careful of kids as drivers of COVID spread.”

Meanwhile, a very small number of children have fallen quite ill as a result of a secondary condition where their immune system has conquered COVID-19 and then goes into overdrive.

Known as multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), immune systems have attacked their own organs, usually two to four weeks after a COVID-19 infection, but most children recover.

A study of New York state cases, until outbreaks stabilized in mid-May, found 0.00002 per cent of kids testing positive for COVID-19 got MIS-C. The United States logged 186 cases between March 15 and May 20.

Carr’s own child suffered from Kawasaki syndrome, which is linked to MIS-C, after an unrelated pneumonia infection, before the existence of COVID-19.

“It is scary, but it’s rare. And it’s very easily identifiable: it’s red eye, it’s a rash,” she says, adding that it would be obvious to everyone if MIS-C was commonplace. “It’s not something you would miss.”

Carr says public-health officials have had to balance controlling the spread of the virus against the impact that keeping schools closed would have on children’s social development.

“When you think about it, we shut down those schools pretty quickly around the world once this started. So we’re still learning now about kids congregating.”

The virus appears to be airborne

Medical experts are increasingly focused on figuring out how effectively COVID-19 spreads in the air. The extent of airborne spread could determine how gyms, restaurants and hospitals are laid out in the future.

Last month, the CDC created confusion by releasing a statement confirming the virus easily spreads through the air, then retracted it, saying it was still being reviewed.

It’s clear that COVID-19 spreads via droplets, and that the largest droplets contain the most virus, but also tend to fall to the floor within two metres. Coughing without a mask likely projects droplets farther.

What’s unclear is whether the virus can hang in the air and drift over an extended distance.

When medical staff intubate someone, tiny particles called aerosols are released from the throat, and they likely contain the virus.

But scientists are looking into whether people also release the virus in aerosols simply through the course of breathing.

That would help to explain situations such as occurred in a restaurant in China, where the virus spread from one part of the room to a corner near an air conditioner, but did not infect people in the centre.

“The viral dose is small, they’re easily dissipated,” Furness says. “But if you’re in a confined space with poor ventilation for long enough, those aerosols are going to have a cumulative effect,” he says. “That is what we think.

“If you end up with enough of a viral dose, and perhaps your immune system is a bit weaker, then you can catch it.”

During the SARS pandemic in 2003, Toronto hospitals built negative-pressure rooms to suck air upwards into filters that capture microscopic pathogens.

If COVID-19 spreads through the air, hospital wards and entire care homes might need to be retrofitted to prevent the spread.

This might be a vascular illness

Scientists know that COVID-19 is a respiratory virus because it attacks the lungs, which also produce droplets.

But it might also be a vascular illness, which is one that creates abnormalities in blood vessels.

“It can probably be both,” Tam said last month.

“Every day you read the scientific literature, this virus seems to have an impact on multiple systems in your body.”

Doctors have documented inflammation in patients’ veins, damaged blood-vessel linings and thickened blood, all unexplained in people who have contracted COVID-19.

The moniker “COVID toes” refers to children and young adults who discover purple lesions or bright-red spots on their feet and hands, which normally stem from exposure to the cold.

Preliminary research shows that some young adults have suffered severe strokes resulting from blood clots, likely from veins lined with COVID-19. However, doctors can now anticipate this risk and use blood-thinning medication.

This disease is peculiar, Furness says, because most viruses target one type of tissue within one type of species.

“What makes COVID quite insidious is that it likes a whole range of cells,” he says, offering the examples of lungs, blood vessel and organ linings.

“If we don’t know the biological mechanism then we’ve got to be pretty worried about it.”

Testing is still tricky

There are three main methods of testing for COVID-19, each of which have different reliability and purposes.

The gold-standard testing used at Manitoba’s Cadham Provincial Laboratory is a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test, which hunts for the genetic material contained within the virus particle.

PCR tests indicate if someone has the coronavirus genome inside their body — but that doesn’t always mean the virus is still active.

“I’d say if you have symptoms that are consistent with COVID, treat them like COVID”– Dr. Anna Banerji

The test is rated as 97.5 per cent accurate, but only when swabs capture the virus, which brings down what scientists call the test’s sensitivity.

The swab might not touch the right part of the throat; up the nose is a better path, but some patients have difficulty tolerating that test.

A patient’s immune system could have already beat back COVID-19 down into the lungs, or the virus could have moved into their veins, leaving no virus for the swab to pick up.

Those issues can bring down the PCR test’s sensitivity down to between 70 and 90 per cent.

“If it’s no longer present in your nose or throat, you can still be very sick,” Furness says. “But the good thing is that if we can’t find any in your nose or throat, you’re not particularly contagious.”

Manitoba chief provincial health officer Dr. Brent Roussin has repeatedly said that someone with no symptoms can be carrying and spreading the virus and get a negative COVID-19 test result.

Banerji is concerned that only people who show up as positive in testing have their contacts traced and isolated. She’s been lobbying officials to tell anyone with symptoms to stay at home.

“I’d say if you have symptoms that are consistent with COVID, treat them like COVID,” she says. “There are so many reasons why this test is not perfect.”

Meanwhile, some people who’ve recovered can still register positive in PCR testing for weeks. The test could be detecting broken shreds of RNA that are still floating around someone’s body, even if the genetic code now lacks the components needed to become active.

In fact, Taylor’s team in Toronto issues letters to patients who have recovered but still test positive.

“Their boss wants a negative swab before they can come back to work,” she says. “(But) they are no longer infectious, and they are safe to return to work — in fact, they may even have immunity and not be able to get COVID again for at least six months.”

Officials have generally discouraged people without symptoms from getting tested, because the results might not indicate whether they actually have COVID-19.

Manitoba is among provinces doing “sentinel surveillance,” where authorities test a random group of people, such as people who are in hospitals for non-COVID issues, for example. The goal isn’t to catch infectious patients, but rather to track over time whether there’s an unanticipated increase in viral spread.

An at-home screening test could come soon

Public-health experts are increasingly focused on at-home saliva testing that advocates say could act as a referral for proper diagnostic testing.

The test is far less accurate than a proper PCR test. It instead looks for antigens, which occur when the immune system is attacking an active viral infection.

“It doesn’t have as much specificity, but it would identify those people with the highest viral load right now, and that might be the most important in terms of getting on top of stopping spread,” Carr says.

Furness and others have criticized Health Canada for being slower than comparable countries in assessing these tests.

The regulator says it needs companies to submit products for assessment, and that it chose to focus first on PCR testing.

Furness says the rapid test would be a tool like a home thermometer, referring super-spreading people for a PCR test.

“The most contagious people are the most likely to test positive,” he says. “We’d be detecting way more cases.”

Meanwhile, research is also underway on antibody or immunity tests that would indicate when someone has already had COVID-19.

Researchers are still figuring out how to reliably test for what’s known as T-cells, which destroy the cells infected with the coronavirus. It’s unclear how long immunity lasts and whether injecting these cells from a recovered person into a sick patient can help them ward off the virus.

The winter will likely cause more spread

Without a human host, coronavirus particles don’t survive very long, and they often die after contact with sunlight.

“That’s relevant for Winnipeg: cold, dry weather in the winter preserves the virus for a very long time,” Furness says, adding that this could also mean more COVID-19 viability on surfaces.

Researchers suspect those were factors in COVID-19 spreading in meat-packing plants.

An August study by Kansas State University found particles remain viable six to seven times longer on various surfaces in temperature and humidity conditions akin to the American Midwest’s autumn season, compared with the summer.

Everyone’s watching for flu cases

Provinces are ramping up orders of this year’s flu vaccine. Because influenza symptoms are similar to COVID-19, the flu could clog testing labs and hospital wards.

But there is some sign for optimism, with various southern-hemisphere countries reporting historically low flu-case numbers during their peak season, which is just wrapping up.

Epidemiologists such as Carr are wondering if social distancing and increased hand-washing have helped bring down the spread, if more people have been vaccinated or if the most prominent variations of influenza this year just happen to be weaker.

Even in the Australian state of Victoria — which had to re-enter a lockdown in July and imposed a curfew in Melbourne — hardly any influenza tests have come back positive since mid-April, despite a similar amount of testing as previous years.

Vaccination might take a while

Canada and other countries are investing in roughly 200 COVID-19 vaccine candidates, giving researchers and pharmaceutical companies the backing to participate in costly trials in the hopes of at least one vaccine proving safe and effective.

Instead of actually curing viruses, most vaccines coach the immune system to respond to a pathogen; jamming the spike proteins the coronavirus needs to penetrate healthy cells, for example.

The hope is for a single shot that prevents the transmission of all strains of COVID-19. But the vaccine might require two or three shots, which would strain the global supply of vials.

A vaccine that must be stored at cold temperatures would add logistical challenges, and if it mutates like the flu there could be a need for annual vaccinations.

Don’t freak out

Everyone interviewed for this article said Canadians should be cautious, but not panic.

They say that public-health officials focus on the amount of risk in specific communities and regions, so that people can calibrate their daily activities.

That often means not just focusing on case numbers, but also the proportion of tests coming back positive and whether the spread has been localized to specific communities.

“False or misleading information can spread as fast as a virus”– Dr. Theresa Tam, Canada’s chief public health officer

The ongoing rise in cases in Ontario and Quebec primarily involves young people, and officials are concerned about that group spreading the virus to grandparents, who could easily strain hospital resources.

Experts acknowledge the constantly changing risk levels have led to confusion.

Meanwhile, a plethora of unreliable information is circulating online.

Canadians are living in an “infodemic” that includes falsehoods deliberately spread on social media, Tam said recently.

“False or misleading information can spread as fast as a virus,” she said. “I urge everyone to consider the source of the information they share with others. And when we come across new information, we need to think critically about it, check the source and not share it further, if there any doubt about its credibility.”

Carr advises people to focus on what we already know works — wearing masks and washing hands.

“A lot of data can make people feel frantic, scared or even helpless,” she says.

“Empowering people… is the only way we’re going to get on top of this.”

dylan.robertson@freepress.mb.ca

History

Updated on Saturday, October 3, 2020 3:35 PM CDT: Correction: A previous version of this story accredited the wrong person to a pull quote. It was Cynthia Carr, a Winnipeg epidemiologist, who said, "What we do know so far is that this virus is not acting like any of the other coronaviruses before."