Manitoba families struggle amid autopsy backlog delays

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 23/09/2020 (1907 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

For 10 days, after her son died of a suspected drug overdose, Margaret Swan waited to see his body and say goodbye.

“I really, really needed to see my son, to confirm that this was reality. Because for a while there, I was thinking all kinds of crazy things and even saying things to family members that maybe it wasn’t really him,” said Swan, a member of Lake Manitoba First Nation.

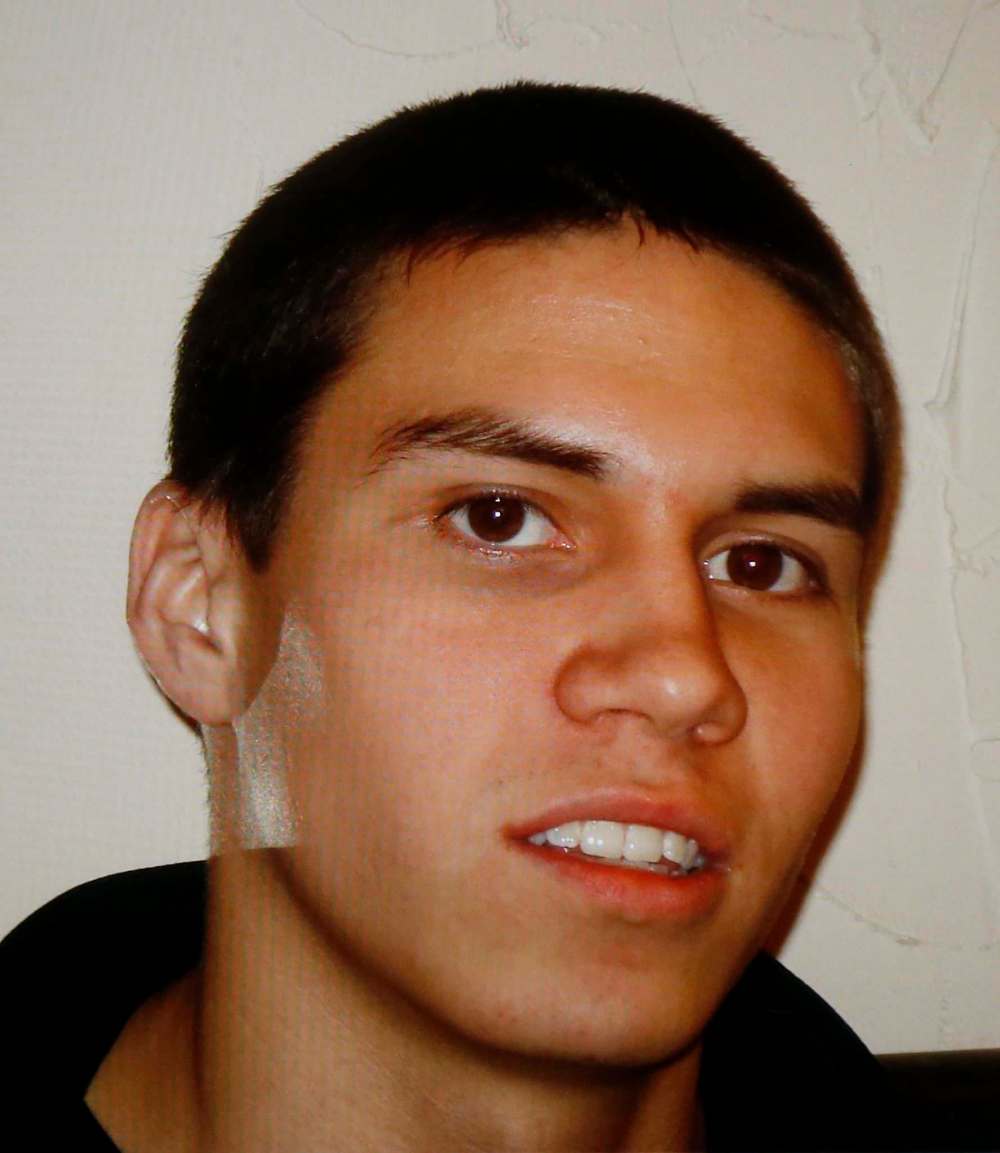

Michael McCartan, 27, died Aug. 15 in Winnipeg. His funeral couldn’t be held until Aug. 26, after his body was released from the hospital to the funeral home.

More than a month later, his mother is still awaiting the autopsy results for what she says police told her appeared to be a fatal fentanyl overdose.

“I really, really did need to see him to help me move forward,” Swan said.

Swan is one of several grieving Manitobans who have experienced lengthy delays in holding funerals for their loved ones because of backlogged autopsies in the province this summer.

Families and funeral directors who spoke to the Free Press said the backlog has been blamed on higher demand for autopsies and a lack of available pathologists to perform them amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Some have been told their loved ones’ bodies had to be stored at a holding facility until an autopsy was ready to be performed in hospital.

Shared Health, the provincial organization that oversees hospitals, said there has been a spike in the number of autopsies conducted during the past several months. During the pandemic, “any death in a personal care home or other facility with a known outbreak (requires) investigation and diagnostic swabs to be taken for the virus,” a spokesman for the agency said.

Timelines for autopsies were “impacted by a surge of cases requiring more complex forensic investigation and COVID-related effects on the workforce,” the spokesman said, adding in a handful of cases, wait times exceeded 10 days.

The agency didn’t make anyone available for an interview, despite repeated requests from the Free Press.

The Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, which investigates deaths and orders autopsies but doesn’t perform them, deferred questions to Shared Health.

On Sept. 8, three men were killed, and another severely injured, when their van was hit by a train east of Strathclair. Among the dead was Phil Houle Jr., whose mother waited nine days to bury her son.

“We were left in limbo. It was very, very heartbreaking… We were left hanging, ‘Where’s the body? Where’s my son?’” Georgina Houle said, breaking into tears.

“Even my grandkids, they kept phoning and asking, ‘What’s the delay?’ I said: ‘I have no answers.’”

The delays have meant disruptions of funeral rituals. In many First Nations communities in Manitoba, Indigenous post-death traditions involve lighting a four-day sacred fire as a symbol of guiding the person’s spirit to the afterlife. Some families start the fire the moment they learn the person has died; others wait till the body has been returned for the funeral.

Joevine Beaulieu, Phil Houle Jr.’s uncle, said relatives lit a sacred fire as soon as they heard about the fatal collision. Two days later, the medical examiner’s office called and said it could take up to two weeks for the autopsy to be done.

“In our Native tradition, we like to bury our loved ones four days after. We have feasts, we have ceremonial traditions that last four days. The ceremonial fire started when we heard of the death… Then I’m getting word it’s going to be a week or two, so we had to go in there and put the fire out,” Beaulieu said.

“We started again on the following Monday. The fire ended the day of his funeral, the embers went out, the flames went out, which is the way it’s supposed to be, but it was almost a week-and-a-half after.”

Brent Buchanan, funeral director at Memories Chapel in Brandon, said there have been lengthy delays with autopsies throughout the summer whenever they are conducted in Winnipeg. He said it has consistently taken one to two weeks for bodies to be released, which has proven hard on families.

“The timeline now is just way beyond what it has ever been. I don’t know what’s going on in Winnipeg and why there’s this big delay, but obviously they’re being overwhelmed,” Buchanan said.

“What is the condition the body is in when we finally do get the human remains? And are we even able to do what we do in our embalming process to give the family a favourable opportunity for visitation?”

As she awaits answers in her son’s death, Swan said she also wants to put a spotlight on Manitoba’s overdose epidemic.

“The police did tell me it was drugs, autopsy will likely confirm that, but for me, either way, I will not get my son back,” she said.

katie.may@freepress.mb.ca

ryan.thorpe@freepress.mb.ca

Katie May is a general-assignment reporter for the Free Press.

Ryan Thorpe likes the pace of daily news, the feeling of a broadsheet in his hands and the stress of never-ending deadlines hanging over his head.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.