Message delivered… but is anyone listening? Communicating about a pandemic is no simple task. As fatigue sets in and as winter nears, it's getting harder to be heard

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 04/09/2020 (1933 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Seven months ago, Dr. Brent Roussin took to the microphone in a lecture hall at the University of Manitoba’s Bannatyne campus in what are now unfathomable conditions for a public health discussion: 50 people, none of whom wore masks, many sitting shoulder to shoulder.

It was a different time, and Roussin, the province’s chief public health officer, was sitting among colleagues in the medical world, trying to execute a gargantuan task: putting into words what he knew — and what he didn’t know — about the novel coronavirus, which had yet to be reported in Manitoba.

Every one sat focused, as Roussin stressed the importance of washing hands, using proper cough etiquette, and not panicking. “We know fear and stigma can often be a pathogen’s greatest ally,” he said. At that point, he said, the risk of the virus spreading in Manitoba was low.

A few weeks later, the first three cases were confirmed in the province, and daily news conferences involving Roussin and Lanette Siragusa, the chief nursing officer of Shared Health, became regular viewing for concerned Manitobans. With thousands of residents at home, the audience was literally captive, hanging on every word.

But as time wears on, risk communications experts and historians say it becomes increasingly difficult to effectively reach the public, even if the risk of infection and transmission continue to be present. Fundamental preventative measures, such as physical distancing and staying home when sick, also can slip from the public consciousness.

“In March, we were dealing with the equivalent of a massive heart attack,” said Robert Steiner, a former health adviser to prime minister Paul Martin during the SARS outbreak in 2003. He now heads the global journalism program at the University of Toronto’s school of public health sciences.

“But we’re in a different world now, and we’re looking at the virus much more like a chronic disease.”

In other words, as Roussin has repeatedly said, we have to learn to live with COVID-19 and its associated trade-offs.

Dr. Sonja Rasmussen worked for 20 years for the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the U.S. and had leadership roles during outbreaks of the 2009 H1N1 influenza, the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, and Zika virus.

She said it’s always more difficult to capture the public’s attention when the threat seems less acute.

“I think the hardest thing about emergency response is that you’re constantly dealing with new information, but you’re also dealing with a population that is in a different place than you are; they aren’t necessarily thinking about (that information) every day,” she said.

“You need to figure out a way to get the messages to them in a way that they’ll hear them.”

“You need to figure out a way to get the messages to them in a way that they’ll hear them.”–Dr. Sonja Rasmussen

● ● ●

Glen Nowak didn’t exactly write the book on communication during a pandemic, but he did co-write the chapter on it in the CDC’s field epidemiology manual, published in 2019.

Nowak’s background made him uniquely positioned to contribute to the chapter, which lays out strategies for public health messages that actually reach the public: he holds a master’s degree in journalism, a PhD in mass communications, and is a professor of advertising. He spent 14 years working at the CDC, including six as the director of media relations. He’s also the director of the University of Georgia’s Center for Health and Risk Communications.

So he knows a thing or two about the challenges of reaching the public.

“One thing is that it’s dangerous to assume that there is a monolith called ‘the general public’” he said. “There are different population groups with different life experiences, different values, and different ways of looking at the world, and that makes it very challenging to do public health communications. There’s rarely an instance where one size, or one message fits all.

“As we’ve seen with COVID-19, there’s no such thing as a single message,” he said during a phone interview with the Free Press.

“As we’ve seen with COVID-19, there’s no such thing as a single message.”–Glen Nowak

The CDC’s guidelines, much like the Canadian federal communications strategy, emphasizes transparency, frequent communications and empathy throughout the pandemic, along with a list of do’s and don’ts.

Do: remain calm. Don’t: let emotions interfere with your ability to communicate a positive message. Do: focus on the facts. Don’t: speculate on hypothetical situations. Do: promise only what you can deliver. Don’t: make promises you cannot keep or fail to follow through on promises made.

Even if those pieces of advice are followed — which is up for debate in Manitoba, where the provincial government’s transparency has been criticized — communication gets more difficult as time goes on, Nowak said.

In the early stages, when the public has less experience with the virus, compliance tends to be relatively high. Over time, Nowak said it’s not uncommon for people to get complacent, which he said happened with HIV-AIDS and takes place every year with seasonal influenza.

“If you’re a relatively healthy person, and you have not seen anybody in your network become seriously ill from COVID-19, you might then surmise that this really isn’t as significant a health threat as it initially appeared to be,” he said.

● ● ●

That could provide a window into Manitobans’ changing psyches as the pandemic moved into the summer. In mid-July, there was only a single active case of the coronavirus in Manitoba, making the province the envy of jurisdictions across North America.

On July 13, after 13 consecutive days with zero cases recorded, Dr. Roussin held to the message that even if the case count dwindled, the threat of the virus hadn’t.

“We can’t let our guards down,” he told reporters. “The low number does set us up for people to think that we’re done with this virus or that this virus is done with us, and I can assure Manitobans that that is not the case.”

For the next few weeks, the province continued to enjoy what some called a pandemic holiday. Then August arrived: from Aug. 4 to 31, the number of active cases rose from 50 to 464 — an increase of 828 per cent.

During a news conference on Aug. 31, Roussin lamented that the average number of contacts per confirmed case had gone up since the start of the pandemic. “To me, that represents stepping back from the fundamentals” of hand-washing and social distancing, he said.

Nowak said that’s somewhat to be expected: the audience hasn’t been able to sustain the same amount of attention as it had in the beginning of the pandemic.

“As this thing evolves, you have to evolve your communications and messaging,” he said. “So really, you end up in a position that looks a lot more like what commercial marketers face every day,” he added.

“Really, you end up in a position that looks a lot more like what commercial marketers face every day.”–Glen Nowak

Steiner of U of T said, “Simply repeating the same mantra over and over again won’t be effective.” So, like Pepsi and Coke, McDonald’s or Popeyes, public health officials have to fight for attention.

Without the capital resources of those behemoths, the message is at risk of being drowned out, Nowak said. In Manitoba, the provincial government has been criticized heavily for running a $425,000 advertising campaign centred on the tagline, “Ready, Safe, Grow.” Its focus shifted to “Know The Facts” once cases began to surge in August.

Reach has always been a challenge for public health officials, said Nancy K. Bristow, the chair of the University of Puget Sound’s history department and the author of American Pandemic: The Lost Worlds of the 1918 Influenza Epidemic.

There are vast parallels between the pandemic of a century ago — in which 20 million to 50 million died globally from the Spanish flu — and COVID-19 when it comes to public response and public health communications.

First, the message was generally to avoid large gatherings and practise proper hygiene.

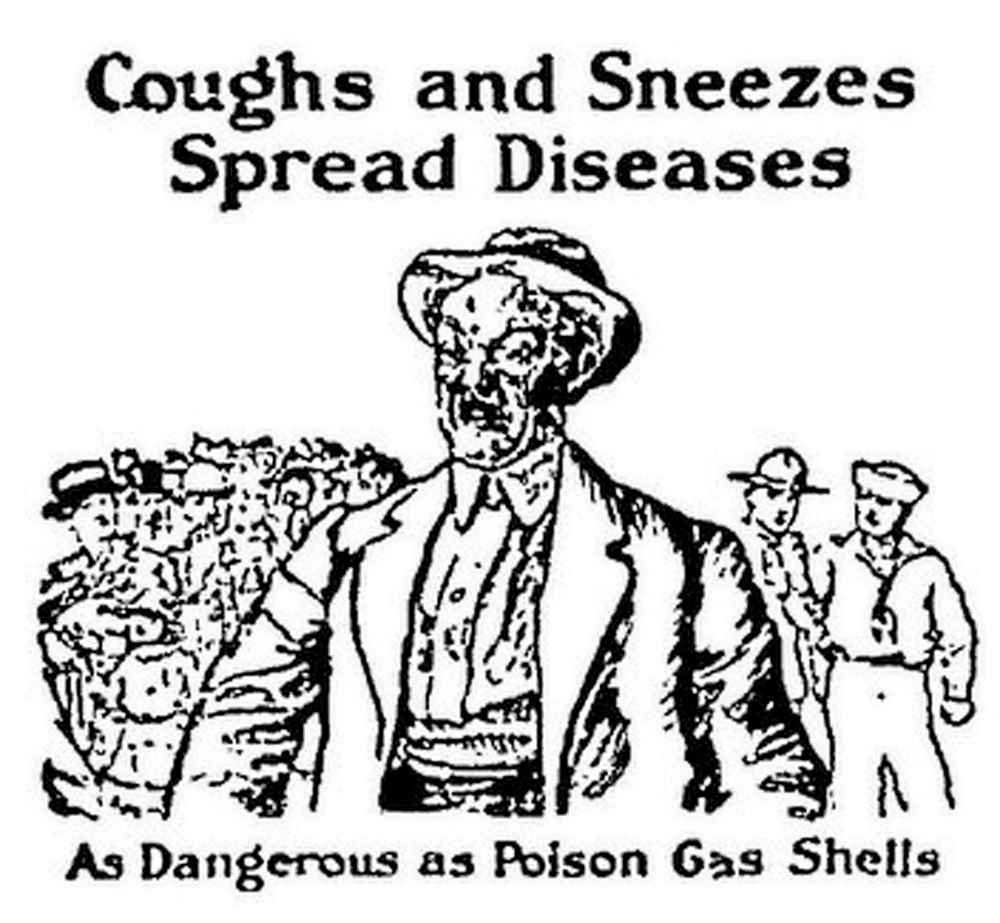

The U.S. surgeon general coined a catchy phrase to prevent the spread of germs: “Cover up each cough and sneeze, if you don’t, you’ll spread disease.”

“As influenza spread, public health leaders called for more significant preventative measures that required Americans to change the patterns of their basic lives,” Bristow writes.

In some locales, common drinking cups were outlawed, overcrowding on public transit was discouraged. Slowly but surely, masks were encouraged for wider use, something 84 per cent of Manitobans would support at all indoor gathering places, according to a recent Probe-EPI poll.

But in 1918, even if citizens followed guidelines at the start of the pandemic, it was often the case that they suffered from the same type of compliance fatigue some people feel today, Bristow said.

“They were, like us, very co-operative at first,” Bristow said, before restrictions were somewhat relaxed and a sense of normalcy returned. “It’s a lot of the same dynamics.”

A good example is San Francisco, where from the relatively early stages of the 1918 influenza, health commissioner William Hassler called for all residents of the city to wear masks on public streets or any place where more than two people assembled, even in their own homes. Anyone who handled or distributed food or clothing had to do the same.

“San Franciscans responded enthusiastically, exhausting the supply of masks as quickly as they were offered,” Bristow writes. Even before it became law on Nov. 1, the vast majority of citizens obliged. The case count dropped significantly, so much so that observers nationwide took notice, and Hassler hoped to keep the masks mandated until the epidemic ended.

Gradually, despite the success of masks to quell the spread of the virus, citizens abandoned wearing them, including the mayor and the chief of the health bureau. By December, with masks in the trash, a new wave started, and infections and deaths surged.

Hassler appealed to the citizens, Bristow writes, reminding them that only a few weeks earlier, a simple change had turned their fortunes around: after that, 90 per cent of the population failed to return to using masks.

“As the epidemic waned, so, too, did Americans’ willingness to accept governmental intervention in their daily lives,” she writes.

One constant message from public health officials has been to remind citizens their own fate is in their hands: measures such as keeping physically distant, while difficult, are much more palatable than infection, illness, or death.

It’s as true today as it was in 1918, and while much of the burden is on public health officials to continue to communicate effectively, public compliance plays an invaluable role in improving the situation in every city, town, or province. As Steiner of U of T said, there are two sides to communication strategies: the people talking, and the people listening.

Historian Alfred Crosby, who wrote a definitive book on the 1918 epidemic, said that even the most extensive public education campaigns would be nothing without the co-operation of the public. “If influenza could have been smothered by paper, many lives would have been saved in 1918.”

ben.waldman@freepress.mb.ca

Ben Waldman covers a little bit of everything for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.