Bound and determined Pandemic, Nova Scotia tragedy powerful reminders that fact-based, responsible journalism matters to readers who matter to us

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 23/04/2020 (1744 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

As the smoke cleared over the wreckage of mass murder, the eyes of a nation turned to Nova Scotia, and to the emerging horror of Canada’s worst spree killing by a lone attacker. On the ground, journalists laboured around the clock to tell the story, to put facts on record, to document the terrible news as it unfolded.

This work, as any sufficiently world-weary reporter knows, is gruelling.

It means ignoring the knot in your gut to make sombre phone calls to suffering families. It means asking sharp questions of tight-lipped authorities. It means contending with the worst of humanity, soothed only a little by the candle-lit flickers of its best.

Yet this work is critical, so it gets done one call, one email or one photograph at a time. Each bit of information so painstakingly collected is given over to public consideration now and saved for its future; someday, historians will turn to what journalists produced in these days to fill in their knowledge of what happened.

To imagine how little we would know about last weekend’s events without those reporters. To think of how they, like everyone else in this industry, had already been under the pressure of pandemic stress. To think of how many were already having to do more work with less.

This is a love letter to newspapers, and to all of their readers. It is also a prayer of sorts for what will come next.

This is a love letter to newspapers, and to all of their readers. It is also a prayer of sorts for what will come next.

Because here is a bitter twist: only four weeks before the killing spree that left 22 dead, SaltWire, a company that owns two dozen daily or weekly newspapers across Atlantic Canada, had issued temporary layoffs to 40 per cent of its staff, amounting to 250 jobs across the company; other staff had their hours (and total pay) cut.

The impacted publications included Halifax’s 146-year-old Chronicle Herald, now doing heroic work to capture Nova Scotia’s trauma and healing. Its newsroom was already shrunk from its peak, buffeted in recent years by layoffs and a gruelling 17-month lockout in 2016-17. And now, in the middle of a pandemic, it was cut closer to the bone.

Although it’s no secret that the newspaper industry has been fragile for years, this was not mere business as usual. SaltWire’s layoffs were yet another casualty of COVID-19. The economic shock of pandemic response has knocked the bottom out of the advertising industry, sending newspaper revenues all over the world into freefall.

Across North America, many papers have issued furloughs and layoffs. Some have simply closed.

Yet the need for journalism has only increased. After the deadly spree last weekend, according to one Chronicle Herald worker, at least two newsroom staff were called back on the job, a testament to the heavy demand their newsroom is under. Newsrooms may shrink, but a community’s stories still need to be told.

Of all the phrases I hope never again to hear or use after the pandemic fades, chief among them is “now more than ever.” It is all too easily said, and yet all too often true; now more than ever do we need strong leadership from government and health authorities. Now more than ever do we need mutual aid and grassroots solidarity.

And now more than ever do we need diligent, comprehensive and reliable reporting.

The pandemic is vast, beyond the actual reach of the virus. There is nothing about our lives or society that its fallout hasn’t touched. Our sports, our entertainment, our business, our recreation, our health care, our education. All of this and more has been left battered and disrupted.

The pandemic is vast, beyond the actual reach of the virus. There is nothing about our lives or society that its fallout hasn’t touched. Our sports, our entertainment, our business, our recreation, our health care, our education.

So journalism must rise to the occasion to document the myriad prismatic facets of change. The work is endless and all-encompassing.

Sports reporters now cover victims of COVID-19. For a while, the Free Press weekend sked, which lays out potential stories for weekend staff, gave simple marching orders: “all virus, all the time.”

We have explored how the pandemic has impacted health-care workers and restaurants and musicians. We have compiled the numbers tracing the spread of the virus and explored how the pandemic has erected new barriers for people who are homeless. And we have kept up with news that changes not just by hour, but by minute.

There is a heavy responsibility to this work. It is a matter of survival. By reporting public-health recommendations, media helps to share the information the public needs to slow the spread of COVID-19; by putting bright lights on government actions, media gives the public the details it needs to scrutinize far-reaching decisions.

Imagine trying to navigate this juncture of history without journalism. Imagine trying to find the light in the darkness with few working reporters left to shine it.

This is a thought exercise for now, but the uncomfortable truth is that one day, it may be more than hypothetical; many journalism institutions are hanging on by a thread.

Imagine trying to navigate this juncture of history without journalism. Imagine trying to find the light in the darkness with few working reporters left to shine it.

At the Free Press, we voted to take a pay cut, knowing that the pain that has rocked so many Canadians would not leave us unscathed. Yet we stand among the lucky, both on the media landscape and the pandemic one as a whole. We still have our jobs. Our work, and all the joy and the pain and the gravity it holds, goes on.

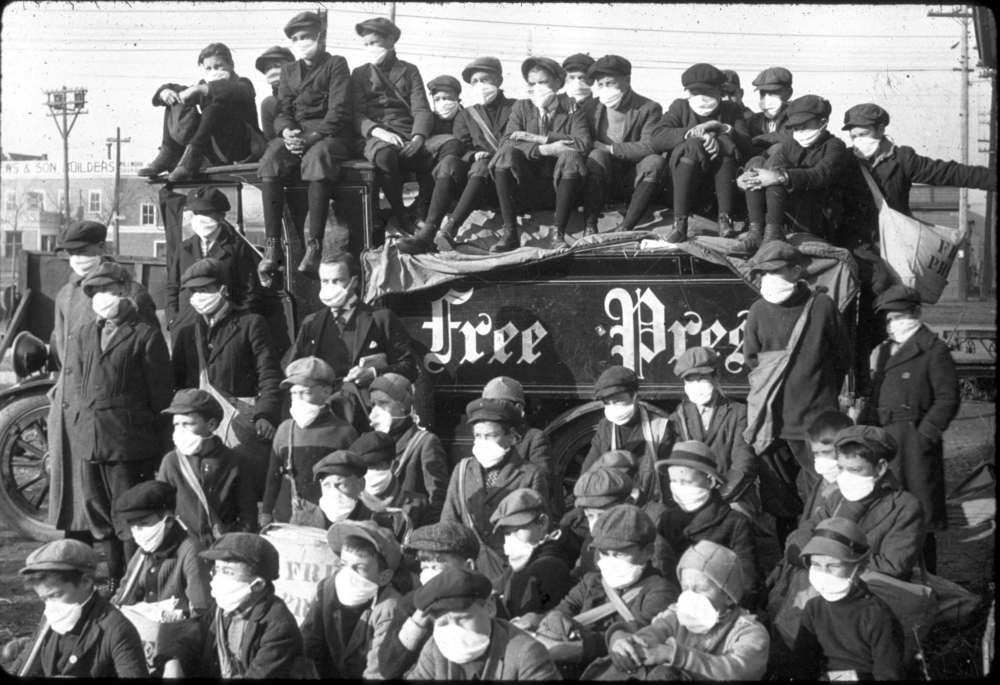

And we are lucky because, after 148 years telling Manitoba’s stories, we have you. We have our readers, and the place this independently owned newspaper has carved out in the community. The Free Press has been bruised by the economic quakes of the 21st century, and now by a global emergency, but we are still spilling ink.

And in the days after publisher Bob Cox wrote about our emergency pay cut and the financial challenges posed by COVID-19, readers rallied around us. Some even sent in cheques, along with kind notes wishing us the best. Many signed up to take the paper; Richardson International chipped in with 100 digital subscriptions.

We felt this support as it flooded in. We feel it now. We are grateful, in ways that sometimes exceed our ability to fully express.

At its best, journalism is a conversation, and the support we have received affirms that our readers have seen us, and heard us, and answered back. That is what allows us to keep moving forward.

This is where a love letter turns to a prayer, and a plea: we need you to stay with us.

Because it is not only the now, the pandemic. It is what will happen after, as advertising is expected to take a long time to recover. Newspapers are in the peculiar position of being read more than ever, but financially supported far less. A recession is coming and a cold, hard fact is that many newspapers will not survive it.

There will be difficult days ahead, and by the time Canada has recovered from COVID-19, few will have not had to sacrifice something in the effort.

There is hope, though. There will always be hope, so long as there are those lights shining in darkness — the letters from readers, the subscribers voicing their support on social media.

Together, we can make it. For weeks, the Free Press has documented the strain of this pandemic; someday, it will come time to celebrate how we rose above it.

When that day comes, we will be there to tell the story — and we will always remember how readers helped carry us through the storm until the rainbow appeared.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Melissa Martin

Reporter-at-large

Melissa Martin reports and opines for the Winnipeg Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Thursday, April 23, 2020 9:15 PM CDT: Fixes typo.