Early federal data contradicts Pallister carbon tax remittance claims

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 02/03/2020 (2109 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

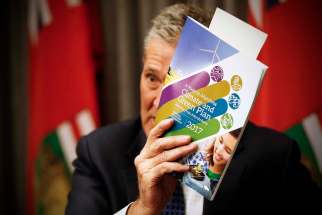

OTTAWA — Manitobans appear to be receiving more than they’re paying into the federal carbon tax this year, despite Premier Brian Pallister’s claims to the contrary.

Although preliminary, new federal data suggest the province is on track to send Ottawa less than what Manitobans will receive in their tax returns this spring.

By law, Ottawa must remit all carbon tax revenues to the province from where they’re collected.

The Canada Revenue Agency provided the Free Press with data showing it received $86,317,000 from Manitobans through the carbon tax’s fuel charge from April to December 2019.

The CRA has earmarked $155,347,000 to remit to Manitobans through their income taxes this spring — this is for the 12-month period that finishes at the end of March, not just the first nine months.

The preliminary figures raise questions about how well the money is being remitted, according to a University of Manitoba sustainability and economics instructor.

“We’re in the good, but it all depends what happens by the end of the (fiscal) year,” said Robert Parsons. “It could go either way. We might be better off, we might be quite a bit worse off; it depends on how the numbers actually work out.”

On average, each Manitoban would have spent $63 on the carbon tax in nine months, and would receive $113 returned for the first 12-month period.

On average, each Manitoban would have spent $63 on the carbon tax in nine months, and would receive $113 returned for the first 12-month period.

Remittances vary based on household demographics and if they reside in a rural area. The new figures exclude the increase in GST charged as a result of the carbon tax, as well as cumulative rises in the cost of products.

Even so, the new figures challenge Pallister’s assertion in January “the federal carbon tax plan takes hundreds of millions of dollars away from Manitoba, and only gives a fraction back.”

It’s unclear how much Ottawa will collect between the start of the January and the end of March. Prorating the first nine months of the year into the subsequent three months would suggest a $43-million overpayment to Manitobans.

However, Parsons believes higher spending on fuels in the winter months could explain the anticipated rise in carbon tax payments between January and March.

Manitobans likely won’t know until the late spring precisely how much revenue Ottawa collected from the carbon tax.

Parsons said Ottawa appears to be accurately estimating the province’s carbon emissions, pegging them around 9.5 tonnes annually in various tabulations.

Yet, Ottawa’s estimates of how much carbon tax it expects to actually collect across Canada has fluctuated. Last June, it estimated taking in $2.1 billion, though by that point it had only dispersed $1.75 billion — a number that has likely since risen.

Ottawa changed its revenue estimate in November to $2.6 billion, after Alberta fell under the federal tax, while New Brunswick negotiated a separate deal with Ottawa. That makes it hard for analysts to scrutinize the tax’s revenue and remittances.

“Based on what I’ve seen from government numbers, I think we’re going to be paying a lot more than what we paid in — but it still remains to be seen,” Parsons said.

The CRA stressed it will give provinces exactly what they paid into the levy. That includes using any estimate for this spring’s income taxes, and making up for an under- or overestimation a year later.

“As actual proceeds and the total amount of proceeds returned in a specific jurisdiction… may differ from estimates, adjustments will be made through changes in future Climate Action Incentive payment amounts, as required,” wrote CRA spokesman Dany Morin.

Pallister disparaged the carbon tax as a “hoax” last year, and more recently claimed the money is leaving Manitoba.

The premier also contended last week the carbon tax will cost Manitobans $1 billion over five years. If the province’s emissions did not change, that would be an accurate cumulative cost as of spring 2023 under the escalating federal tax, though the federal law holds this cash still has to be remitted.

Parsons, who studies how economic measures interact with sustainability, is pessimistic the carbon tax will do much to drive down Manitobans’ emissions.

The levy is predicated on the idea raising the cost of fuel will make people drive less, and buy more efficient vehicles. However, gas prices fluctuate much more now than a decade ago, to the point a carbon levy becomes hardly noticeable, he argued, especially because it starts at only 4.42 cents per litre.

“When you look on the gasoline side, (the decline) really isn’t all that consequential,” said Parsons, who conversely argued the tax on diesel is also raising the price of goods, due to added freight costs.

However, gas prices fluctuate much more now than a decade ago, to the point a carbon levy becomes hardly noticeable, he argued, especially because it starts at only 4.42 cents per litre.

“My sense is we’re being set up for to fail; that there’s been so much of a dogmatic pursuit of carbon taxation that it’s not going to work.”

Ottawa has designed its carbon tax to remit 90 per cent of the tax through income-tax top-ups, while the rest will fund carbon retrofit programs.

For example, Ottawa allocated $5.4 million last August for Manitoba school divisions to retrofit classrooms, though that money appears to not have yet flowed.

The new figures do not include the cap-and-trade regime that governs a handful of industrial plants in the province, who pay into a separate levy based on their carbon outputs.

The Supreme Court will hear arguments later this month on whether the carbon tax has Ottawa unconstitutionally weighing into provincial jurisdiction.

dylan.robertson@freepress.mb.ca