Ending birth alerts requires new programs, province warned

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 03/02/2020 (2136 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

OTTAWA — Child-welfare experts from across Canada are disputing the Pallister government’s claim it won’t need to put up more cash to phase out birth alerts in Manitoba.

“Absolutely in child welfare, the devil is in the details,” said Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond, a former Saskatchewan judge who specializes in child welfare.

Birth alerts will end through directive: province

A Manitoba spokeswoman said that instead of passing a law or issuing regulations, the province will work with the province’s four CFS authorities “to finalize changes to child welfare standards that are needed to eliminate birth alerts.”

The province claimed that currently, “children are only taken into care by an agency as a last resort when serious safety concerns exist and cannot be adequately addressed in the home in partnership with the parents or guardians,” however, numerous Indigenous leaders have disputed this claim.

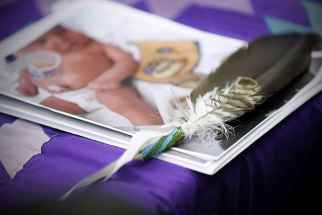

A year ago, a family live-streamed the apprehension of their newborn in a Winnipeg hospital on Facebook Live, attracting national outcry.

A Manitoba spokeswoman said that instead of passing a law or issuing regulations, the province will work with the province’s four CFS authorities “to finalize changes to child welfare standards that are needed to eliminate birth alerts.”

The province claimed that currently, “children are only taken into care by an agency as a last resort when serious safety concerns exist and cannot be adequately addressed in the home in partnership with the parents or guardians,” however, numerous Indigenous leaders have disputed this claim.

A year ago, a family live-streamed the apprehension of their newborn in a Winnipeg hospital on Facebook Live, attracting national outcry.

The mother in that case, who cannot be identified by law, has claimed she had a birthing plan to have her great-aunt take the child, who was apprehended anyway and later placed with that relative. The province said it always tries to find a family match when a parent can’t take their child home, and that sometimes another option has to do in the meanwhile.

“Ideally, this planning is done as early as possible to ensure that extended family members can be part of the process to ensure a safety plan is in place for the child,” the province wrote.

The spokeswoman, who would not be named, stressed that birth alerts will be phased out, and not just eliminated in name only.

—Dylan Robertson

“I can’t see the issue being resolved without new resources.”

Manitoba made national news last Thursday when Families Minister Heather Stefanson announced the province would stop Child and Family Services (CFS) agents from issuing birth alerts as of April 1.

Currently, the families department asks hospitals to notify agencies when a mother they deem to be high risk is having a child, in case they need to apprehend the baby immediately.

Manitoba has Canada’s highest per capita rate of children in CFS care, 89 per cent of whom are Indigenous. About 500 birth alerts have been issued in most recent years, though the number has slowly declined.

Last week, Stefanson suggested the province would not need to fund programming to end the practice.

“Those organizations are already out there; they’re already doing this, so they’re already funded in various ways,” she told reporters.

Stefanson would not give an interview Monday, but her spokesman reiterated that “ending birth alerts does not require additional funding,” because resources already exist.

However, British Columbia boosted pre- and post-birth programming last September when it announced its own end to birth alerts in that province.

Turpel-Lafond, who is now a prominent law professor at the University of B.C., said that included substance-abuse programming that allows mothers to attend with their children. B.C. also promoted breastfeeding, and training for parents whose own families had been traumatized by domestic abuse, residential schools and the Sixties Scoop.

“You have to fund pre-natal and post-natal care,” she said.

Cheryl Casimer, political head of the First Nations Summit, said B.C. is still working out programming, but recognized that families needed training and support if apprehensions were actually going to decrease.

“If you don’t put the proper roots in place to help moms and families, it won’t be a birth alert but it will be another situation right down the road where you’re dealing with an apprehension,” she said.

“If you don’t put the proper roots in place to help moms and families, it won’t be a birth alert but it will be another situation right down the road where you’re dealing with an apprehension.” – Cheryl Casimer, political head of the First Nations Summit

Casimer said B.C. made the change in lockstep with Indigenous communities, sharing with them the directives it was issuing to agencies.

“We had a really rocky start and I think it’s the same in most provinces,” she said.

Manitoba’s First Nations and Métis leaders have expressed support for ending birth alerts, but have also asked for details from the Pallister government.

As of January, all provinces have had to ensure that CFS agencies comply with federal legislation that took affect on Jan. 1. Known as Bill C-92, the law enforces a national standard on child welfare.

That includes removing a child from its family as a last resort, and if so, demonstrably attempting to place the child in a home that that keeps up its Indigenous culture.

Turpel-Lafond added a court would likely have found Manitoba’s birth alerts illegal under Bill C-92 if it hadn’t scrapped the practice voluntarily.

She said Saskatchewan officials are closely watching how Manitoba’s proceeding. “It is a step in the right direction; it’s not the complete journey yet,” she said

A provincial spokeswoman said Manitoba “will work with public health and expectant parents to create better connections to help the expectant mom access preventive and supportive programs, so we can work together to keep families together.”

Jane Philpott, the former Indigenous-services minister who helped craft Bill C-92, said she was alarmed when she first learned how pervasive birth alerts were in Manitoba.

“In circumstances where there might have been a birth alert in the past, what is being done to support parents and children to be successful as a family?” she pondered on Monday.

“”It goes before the time of birth, ideally.”

Philpott gave the example of the Early Years project run by Maskwacis Four Nations in Alberta, which trains local people in both first aid and mental health as well as culture and language. The staff do home visits to pregnant moms and new mothers followed by pre-school programming for the kids.

Philpott said she was glad to see Manitoba end the practice, and was unsurprised a provincial review found there was no evidence the practice didn’t actually make kids safer.

“It’s hugely upsetting because it makes you realize this practice has been going on for years now; it was never evidence-based and a lot of harm has come to families because they were separated inappropriately.”

dylan.robertson@freepress.mb.ca

History

Updated on Tuesday, February 4, 2020 12:29 PM CST: fixes typo in quote