The complicated legacy of Kobe Bryant

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 28/01/2020 (2144 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

When the news broke Sunday basketball star Kobe Bryant had been killed in a horrific helicopter crash outside Los Angeles, the outpouring of grief and shock was swift. All nine people on-board died, including Bryant’s 13-year-old daughter, Gianna, a promising young athlete in her own right.

The facts of the 41-year-old’s life have spilled out in news stories and tributes over the past few days, many of which have been hastily compiled to keep up with the news cycle.

Kobe Bryant was an exceptional athlete, an icon. Kobe Bryant was a loving husband and dedicated dad to four daughters. Kobe Bryant meant a lot to a lot of people. Kobe Bryant was charged with sexually assaulting a 19-year-old woman in 2003, when he was 24 years old.

All of those statements are true. Except, we’re not supposed to talk about that last one.

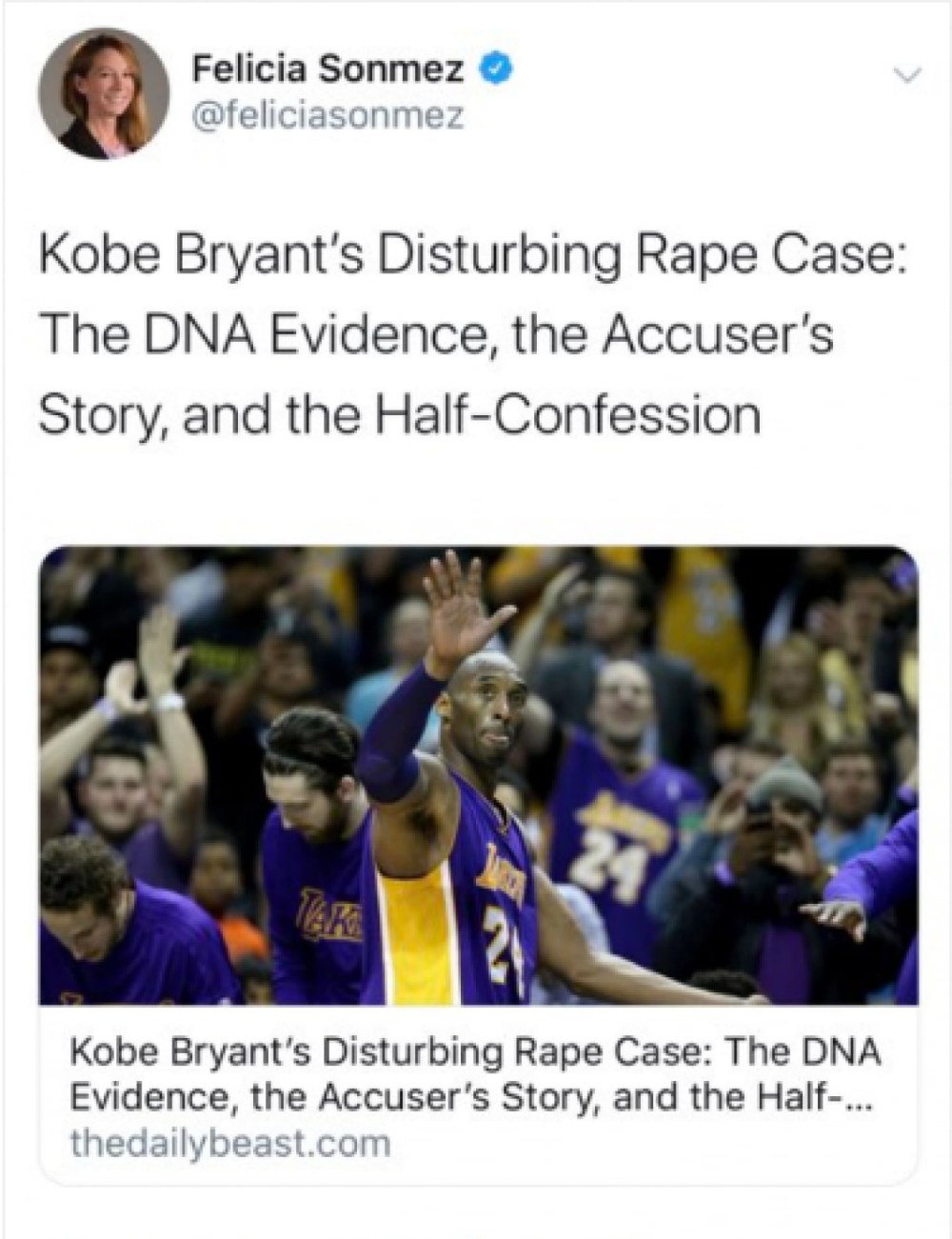

Washington Post reporter Felicia Sonmez, herself a survivor of sexual assault, learned that Sunday, when she was placed on administrative leave after tweeting a link to a reported piece from 2016 about Bryant’s rape case.

(Bryant reached a settlement with his accuser out of court in 2005. Notably, Bryant apologized, saying: “Although I truly believe this encounter between us was consensual, I recognize now that she did not and does not view this incident the same way I did.”)

Sonmez did not provide any of her own editorial comment on the link, nor was she the author of the piece. And still, thousands of people sent her threatening and abusive messages, one of which she screengrabbed and tweeted out.

Marty Baron, executive editor of the Post, subsequently sent an email to Sonmez, which was published in the New York Times. “Felicia,” Baron wrote. “A real lack of judgment to tweet this. Please stop. You’re hurting this institution by doing this.”

That the Post didn’t support its reporter is galling. A media organization should not allow readers to abuse its reporters. A paid subscription does not earn one the right to call a female journalist the c-word. A thick skin won’t save a life if someone decides to make good on a death threat.

Many other Post journalists agreed. More than 300 signed a letter on behalf of NewsGuild, the union representing Post journalists.

“The loss of such a beloved figure, and of so many other lives, is a tragedy,” the letter reads in part. “But we believe it is our responsibility as a news organization to tell the public the whole truth as we know it — about figures and institutions both popular and unpopular, at moments timely and untimely.”

By Tuesday night, Sonmez was reinstated. The Post, however, did not condemn the harassment that forced its reporter to stay in a hotel Sunday night, instead expressing regret about “having spoken publicly about a personnel matter.”

Journalists, especially, should not be in the business of hagiography. Yet, grief has a way of making saints out of all of us, from the famous to the ordinary. That’s why honest obituaries tend to go viral: we’re not used to seeing unvarnished truth in death.

It’s disrespectful, we’re taught, to speak ill of the dead. We’re taught there’s “a time and a place” — even though that time and place is too often never and nowhere.

Imagine how a sexual assault survivor might feel seeing all the glowing tributes that erase the messiest, most difficult parts of Bryant’s story. Or watching a trusted news organization not stand up for an employee drawing attention to the harassment she received for tweeting out a link to a story that’s true. Or seeing people call a female reporter disgusting names for the reminder their hero was charged with sexual assault.

A big part of the #MeToo movement has been to take a sledge hammer to the pedestals we place rich, powerful, influential men on — the very pedestals that allow them to act with impunity because they are too big for their actions to have consequences. We do that by telling the truth.

People’s lives, and legacies, are complicated. Grief is complicated. It’s hard to reconcile your love for someone and the idea they hurt someone else. However, as author Jill Filipovic wrote on Bryant: “Awe without honesty isn’t respect; it’s myth. Admiration of only the easy parts is fanaticism, not reverence. And if we want a world in which our stories are more honest than the heroes-and-villains framework allows, then we have to start by telling the whole truth.”

Here is the truth: Kobe Bryant was an exceptional athlete, an icon. Kobe Bryant was a loving husband and dedicated dad to four daughters. Kobe Bryant meant a lot to a lot of people. Kobe Bryant was charged with sexually assaulting a 19-year-old woman in 2003, when he was 24 years old.

All of those statements are true. We need to be able to talk about all of them in order to remember the man. Not the myth, not the legend.

jen.zoratti@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @JenZoratti

Jen Zoratti is a Winnipeg Free Press columnist and author of the newsletter, NEXT, a weekly look towards a post-pandemic future.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.