Pleased to Met you! Alternative, hands-on education model giving passionate teens a taste of life at a newspaper and giving the Free Press a glimpse of its future

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 24/01/2020 (2145 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In the airy cafeteria commons of Maples Collegiate, a few hundred students sit in an attentive but youthfully restless quiet, listening to the young woman on stage. Her name is Lena Andres, and she is not much older than the Grade 4 through 10 students who came to hear her; she graduated high school just last year.

Andres is already a rising youth leader. A University of Winnipeg student, she is a key organizer of Manitoba Youth for Climate Action, which spearheaded the march on downtown Winnipeg in September. So the topics she raises in her keynote for this student-led Global Citizenship Conference are already familiar.

“Does anybody know Greta Thunberg?” Andres asks the crowd.

From every chair in the room, hands shoot up. They all know Greta Thunberg.

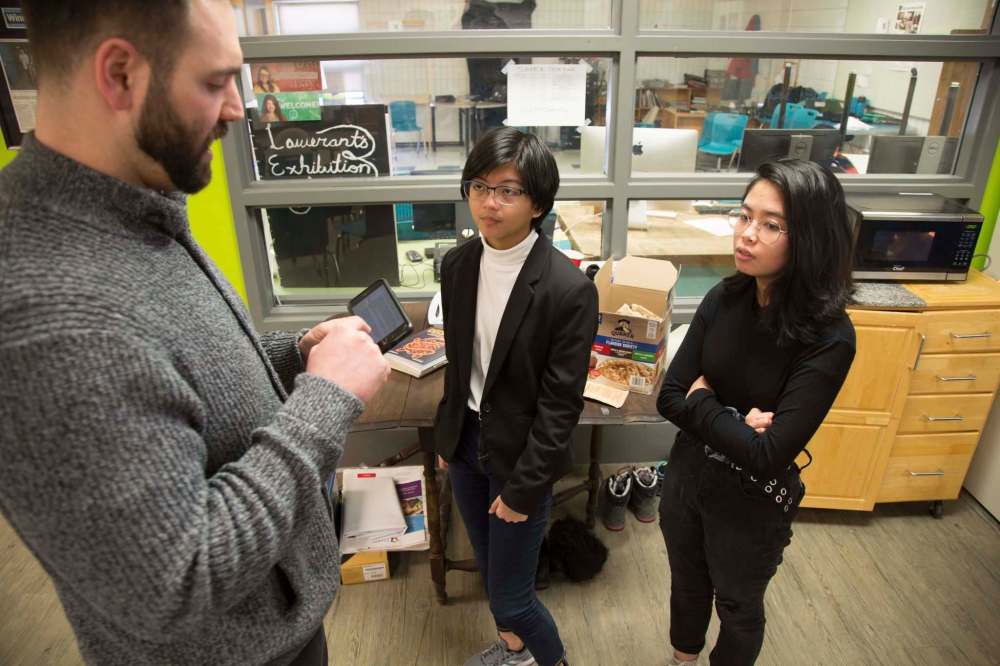

At a table near the back, Alex Payawal and Rory Ramos sit rapt, taking careful notes on a slim pad of paper. They are both 14 years old, Grade 9 students at Maples Met School, one of two such innovative “Big Picture Learning” facilities in the Seven Oaks School Division, and they are listening for ideas to develop into a full-fledged story.

“I want to write something connecting to what she said about ‘power to the people’ and stuff like that,” Rory says.

•••

When Andres is done speaking, the students file through the labyrinth halls of Maples Collegiate and back to the snug warren of rooms that houses Maples Met. In those rooms, Grade 12 Met students are preparing workshop presentations on topics of broad global interest: dengue fever, for instance, or Chinese politics.

In the Maples school’s open Great Room, Alex and Rory flit between doors, taking note of each topic on offer. They settle on one focusing on the refugee experience and flip open their notebooks while younger students fill up the room. Just then, principal Ben Carr breezes in to check on how they’re doing.

“This is a good one to be at,” he whispers, and the girls smile.

In a way, the Great Room carries the same buzz as a newsroom, the same constant hum of footsteps and conversations and shuffling paper. But the world in which these students move is little like the work world in which most Canadian journalists are immersed, and that fact demands attention.

For one thing, it’s vastly more diverse, particularly along ethnic lines. Many of the students here are children of immigrants, or were born abroad themselves; the majority are not white. Their Canada is a young one, globally connected, growing together on the Prairies from roots laid across the world.

Canadian newsrooms, on the other hand, are infamously homogenous. A 2000 Laval University study found that a whopping 97 per cent of journalists in Canada were white and, in many newsrooms — the Free Press included — this has shifted little in the last 20 years, even as the country itself has changed around them.

This fact was not lost on Alex and Rory when they toured the Free Press newsroom last month. Their own family members, they agree, are more connected to news coming from the Philippines than from Canada; they don’t see nearly the same level of awareness in the daily paper.

And the students’ media world, especially, is vastly unlike the one most journalists working now grew up in. Their generation, more than any before, is saturated by news, and particularly by the roiling dialogue around hot-button issues. They get their news from all over: from YouTube, or video app TikTok or Instagram.

This does shape their outlook, in ways that older generations may not intuitively understand. To sit with them in conversation is to learn that they are incredibly well-versed in the issues of the day. They discuss everything from climate change to poverty and international conflict with their friends, they say.

“I’m really hyper-aware of these social issues,” Alex says. “It’s one of the main reasons why I’m still very much into politics. If the internet wasn’t a thing, I don’t think I would have carried on with my interest. It’s the reason I went to multiple climate marches. I see how it affects other people my age who I engage with online.”

The flip side, they agree, is that this conversation is dominated by American issues. When the marketplace of ideas goes global, its parameters are often set by the loudest voices in the room, or just the wealthiest. Rory gets her local news from TV, which she watches daily with her parents; it makes up less of Alex’s media diet.

They know that’s something that needs to change, on a broad level. They also know that it’s tricky.

“How are you supposed to ask somebody to be more interested in a small local story that isn’t very exciting, instead of paying attention to, like, the U.S. and Iran?” Rory says. “In movies or in entertainment, it’s always driven to higher stakes, where it makes you pay attention. The local stories aren’t as interesting.”

For years, Canadian newsrooms have been wrestling with how to adapt to those realities, and how to make their newsrooms better reflect the communities they cover. That’s been a challenge in a media industry struggling with collapsing revenue models; but these students’ generation could be the one to find the solution.

The question is not one of diversity for the sake of diversity: it is one of staying relevant. Once, a friend approached me, wondering why no media in Winnipeg had covered a story about a local person who was having success in the Philippines. His relatives on both sides of the ocean were buzzing about it on social media.

The truth is, I responded, the reason it wasn’t covered was likely quite simple: nobody in Winnipeg media knew about it. The Free Press has no Filipino journalists on its staff even as that community has become integral to the city’s social and cultural makeup, and so we are inherently less connected to its experiences.

If a newsroom does not reflect the community that it covers, if it does not understand the world in which its readers move, the discussions they are immersed in and they way they engage them, then what is it missing? What voices are left out of the conversation, what issues relevant to them are missed or glossed over?

With that in mind, this year the Free Press is partnering with Maples Met School to develop a new project, one to link curious young writers such as Alex and Rory with opportunities to explore the journalism field. What form that ultimately takes is still taking shape, but this much is certain: you will see their writing in these pages.

There is something they can learn from us, sure, but also much that the Free Press and its readers can learn from seeing the world through their eyes. Maybe some 14-year-olds would be intimidated by the idea, but Rory and Alex are just excited about trying something new.

After all, at this school, that’s sort of what they do.

•••

In his office, a windowless wedge of space decorated by a painting of a polar bear and a quote from Martin Luther King, Ben Carr leans back in his chair and considers the media world his students are immersed in. He’s seen the same things that I did, in conversation: the breadth of their knowledge, but also how it’s driven.

“There is a blessing and a curse to the way that media is available to young people today,” he says. “On one hand, they’re way more informed, I think, than any generation ever before… but where I think it’s a big problem, and social media plays a significant role in this, is it has become sensationalized.”

It’s been a year since Carr arrived here as principal, where he serves as lone administrator. There are 145 students under his wing, and the school’s tiny size and unique educational structure means he gets to know them well. At times, his job is a bit like an air-traffic controller, shepherding a multitude of students in motion.

“It’s just a little nutty around here,” he says with a good-natured shrug. “A single call can derail the whole day.”

The Met school concept — also known as “Big Picture Learning” — originated in 1995, when Rhode Island educators Dennis Littky and Elliot Washor launched an innovative concept. They wanted to shift focus away from rote learning and standardized tests, to a vision of education that was individually tailored and student-led. The doors to The Met — the Metropolitan Regional Career and Technical Centre — opened shortly after.

That idea soon caught fire: there are now nearly 200 Met schools worldwide, but the two in Winnipeg are the only ones in Canada. There is Seven Oaks Met, which opened inside Garden City Collegiate in 2009 and now has its own facility across the street on Jefferson Avenue, and Maples Met, which launched seven years later and is located in the Maples Collegiate complex, also on Jefferson Avenue.

The differences between a Met school and a traditional one start on the surface, but run much deeper. Teachers here are known as “advisers,” and students call them by their first names. They also roll through the years in sync with students, providing a consistency of the educator-student relationship through to graduation.

What makes Met really different, though, is how students learn. Beginning in Grade 9, they seek out internships at companies, non-profits or organizations in the wider community; they also develop their own projects that may take months of hands-on learning, as well as problem-solving that crosses multiple scholastic disciplines.

They must still hit the standard curriculum milestones, so students do take some traditional classes, including math and phys-ed; they can also choose to take band or other electives at Maples Collegiate. But most of their learning happens through the other, more hands-on and community-immersive routes.

Each week, Carr and the advisers put out an email newsletter, with updates on what students have been pursuing. The topics can be dizzying: this week, a Grade 10 group is designing an entire civic downtown. A Grade 11 student got an invitation from a local MP to discuss a parliamentary bill that concerns restorative justice.

The internships, too, take students far afield. One Grade 9 student just started an internship at the Craig Street Cats shelter; a Grade 12 student has been interning at the regulatory body, Engineers and Geoscientists Manitoba. Over the years, Met school students have interned everywhere from bakeries to pharmaceutical labs.

The impacts of that sort of hands-on education, Carr says, are remarkable, sometimes even visible.

“The biggest thing is confidence,” he says. “We have a lot of kids come in here in Grade 9 who couldn’t utter a word publicly, maybe even next to the person next to them. Within a month or two months, they are completely different in terms of introducing themselves, what they’re passionate about, what they’re working on.

“You should see when a Grade 9 kid lands their first internship, it’s an exciting thing,” he adds. “It’s, ‘Ben! Guess what? I got an internship!’ The aspect of belonging is so critical for young people, and getting an internship is a validation, because it’s an adult saying, ‘Yeah, I recognize something in you. I want to work with you.'”

A newspaper is a new addition to that roster of potential internship partners. Carr is more familiar than most with the business: he writes occasional columns for the Free Press and his father, Winnipeg South Centre MP Jim Carr, was once a journalist and editor at the paper.

So when Free Press editor Paul Samyn first suggested a collaboration, Carr was ecstatic. He thought right away of Alex, Rory and another student, Kalkidan Mulugeta. They’d all expressed interest in journalism or writing; Kalkidan, who is in Grade 11, already has a internship reporting for Christian radio station CHVN.

To Carr, the benefits to the students are self-evident. It’s partly a chance to explore their curiosity about community, he says, but also to sharpen their approach to the ideas that so engage them. Journalism requires a way of thinking about subjects, a certain clarity about all the angles and precision of intention.

“It’s really important that they learn how to communicate onto paper the thoughts that are permeating in their minds, and how they learn to understand themselves as critical thinkers,” he says. “(Reporting) is not like a diary entry… it’s, ‘I have to really have an understanding of how people think.'”

The school now has a subscription to the paper, and each morning students mingle in the Great Room, flipping through its pages, discussing articles about the city in which they live. It’s an antidote maybe, for the disconnect happening between local news and the social dialogues the youth are immersed in.

On the way out, I tell Carr that I wish the Met concept had existed when I was young. He shows no surprise.

“That’s actually the most common thing we hear from adults who visit,” he says.

•••

Two days after they sat taking notes at the Global Citizenship Conference, Rory and Alex slip into chairs in an empty classroom, still buzzing over what they heard in the presentations. Alex was most inspired by a presentation on the Spanish occupation of the Philippines; Rory is planning to reach out to an Afghan refugee.

For the Free Press project, they are open to how it develops. Their eyes light up when it’s suggested they might get out into the field to do interviews and do some reporting. They may get their media mostly online, but it appears the idea of having an article published in the paper, read by tens of thousands, still holds a certain cachet.

“It would be really cool if we wrote a story,” Rory says. “It would be a neat experience having written a story at 14 or 15, and the knowledge that it gives you… being able to say that this is the stuff the Met School does for you, these are the doors that it opens.”

Alex nods in agreement and giggles. “I can be the favourite grandchild now,” she says.

This is the energy Canadian media needs to be renewed. Whatever happens with this project, the future of news in this country will be written by young people like them, and it depends on them, too — on their curiosity, their questions, their views. Regional media has not always succeeded at nurturing them.

Hopefully, that can start to change — and maybe it begins with a spark of an idea, and an invitation.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.