Unstable building named after someone who didn’t deserve honour

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/01/2020 (2154 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It’s odd that a building was ever named after Thomas Scott, an insignificant Canadian “loyalist” foot soldier in 1869-70 Red River. But 117 years after it was erected in Winnipeg’s Exchange District, the dilapidated three-storey Thomas Scott Memorial Orange Hall on Princess Street may soon have a date with the wrecking ball due to serious structural problems.

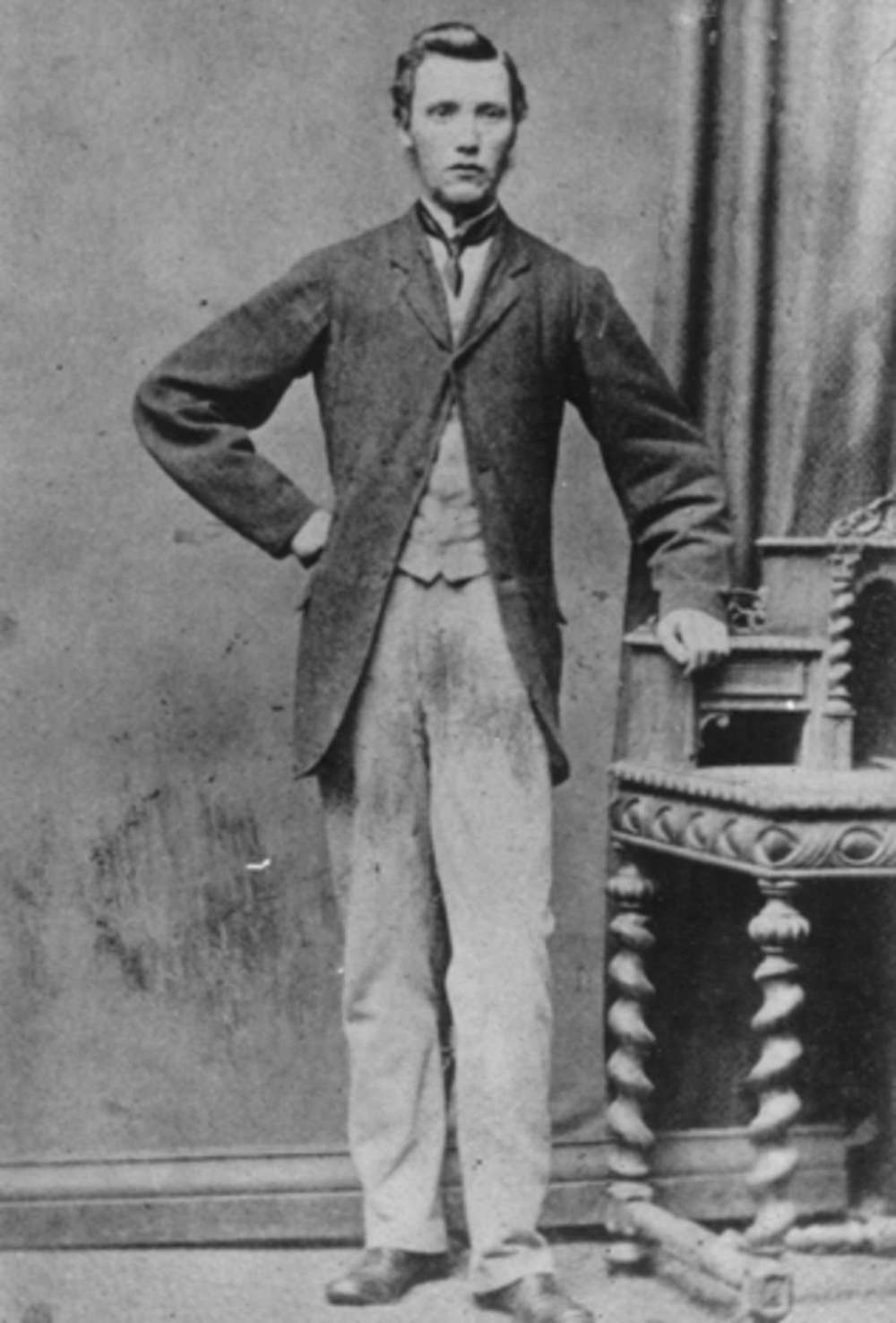

Scott, who was born in Clandeboye, Ireland, around 1842, came to Red River in the summer of 1869 from Ontario, just when Louis Riel and the Métis resistance was beginning to take shape. He worked briefly on a road construction project in northwestern Ontario, where he was fined four pounds after being convicted of threatening to drown the foreman on the job.

A growing number of Canadians began trickling into Red River at the time, in anticipation of its annexation to Canada. An unmarried, transient Scott was among them.

The so-called Canadian loyalists in Red River, led by John Christian Schultz, opposed the Métis resistance. They were apoplectic when Riel and his men blocked lieutenant-governor designate William McDougall from entering the territory in November 1869. The Canadians made several failed attempts at organizing armed rebellions against Riel and his provisional government. For that, many were captured and held as political prisoners at Upper Fort Garry, which the Métis had seized.

Prisoners frequently escaped the fort, were recaptured and, in some cases, escaped again. Scott was among dozens arrested by the Métis following a dramatic armed standoff at Schultz’s home in the town of Winnipeg in December 1869. He escaped the fort in January, but was recaptured with others the following month after another failed attempt to overthrow the provisional government.

This time, he didn’t get out alive.

Scott made no meaningful contribution to anything during his short stint in Red River. He wasn’t a leader among the Schultz crowd and played no significant role in organizing its failed armed rebellions. He was a nobody, a transplant from Ontario looking for some future opportunity possibly to arise with Canadian annexation. Scott’s only real claim to fame was his execution by Riel’s provisional government.

Plenty has been written about Scott, then about 28 years old. He’s been branded a bigot, a racist and a drunk, although the historical record is sketchy, if non-existent, on many of those characterizations. He certainly was no friend of Riel and the Métis. There are varying accounts of how he heaped verbal abuse on Métis guards. He allegedly struck one of them, which formed part of the charges that led to his conviction of “insubordination” against the provisional government.

On March 4, 1870, after a trial of just a few hours the day before (Scott had no representation and had little grasp of the proceedings, conducted in French) he was walked outside the walls of Upper Fort Garry and executed by firing squad.

It was only after his execution that Thomas Scott’s name took on martyr-like proportions. Schultz, who fled to Ontario, and others from the Canada First movement (a secret society of Anglo-Saxon Protestants) as well as the Orange Order in Ontario (an anti-Catholic fraternity of Protestants) vowed to avenge Scott’s death. They used the execution to whip up opposition in Ontario against Riel and the Métis, casting them as murderers and enemies of the Queen. Suddenly, Thomas Scott became a household name and the face of the Orange Order.

There’s some question whether Scott was even a member of the Orange Order. Had he been — and had Riel and others in Red River known about it and saw Scott as a significant player among Canadian loyalists — they may have thought twice about executing him. They couldn’t have possibly known Scott’s killing would have triggered the furor it did in Ontario.

Nevertheless, the Orange Order in Winnipeg saw fit to name its new building in the Exchange District after Scott three decades later as if he truly was a martyr, or made a significant contribution to anything.

It’s always a shame to lose a heritage building. And if the one at 216 Princess has to be demolished, it will be regrettable (especially since it appears to have been preventable). But there will be no loss in Thomas Scott’s name coming down with it. He never deserved to have a building named after him in the first place.

tom.brodbeck@freepress.mb.ca

Tom has been covering Manitoba politics since the early 1990s and joined the Winnipeg Free Press news team in 2019.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.