Archaeology unearths proof of huge 1285 meeting

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 25/11/2019 (2209 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In 1988, after a long day of digging up pottery shards and catfish bones at the Forks, archeologist Sid Kroeker was approached by two elders.

They told him they wanted to share a very old story with him, passed down through their families, about the lands he was working on.

They told him that, over 700 years ago, 10,000 people came from hundreds of miles away and from dozens of communities to meet at Nistawayak (“Three Points”, the original Cree name of the Forks).

During a time of great struggle and war, this huge group held a meeting and, after weeks, signed a treaty, forging peace throughout territories now known as Ontario, Manitoba, North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota, Michigan, and Wisconsin.

Without this peace, they said, there would not be the Manitoba we know today.

His curiosity piqued, Kroeker couldn’t find research on this treaty nor evidence in the archives.

This story, however, stuck with him.

Now, over 30 years later, science is catching up to oral tradition in a new exhibit at the Manitoba Museum.

For nearly four decades, archeologists, historians, and anthropologists have known that, for over 6,000 years, hundreds of thousands of peoples lived, worked, and traded at the Forks, Nistawayak.

Much of this history has been uncovered by the millions of items they left behind. Fish and animal bones, pottery shards, and arrowheads, however, only tell one part of their lives; the people who inhabited Nistawayak left political, cultural, and social legacies too.

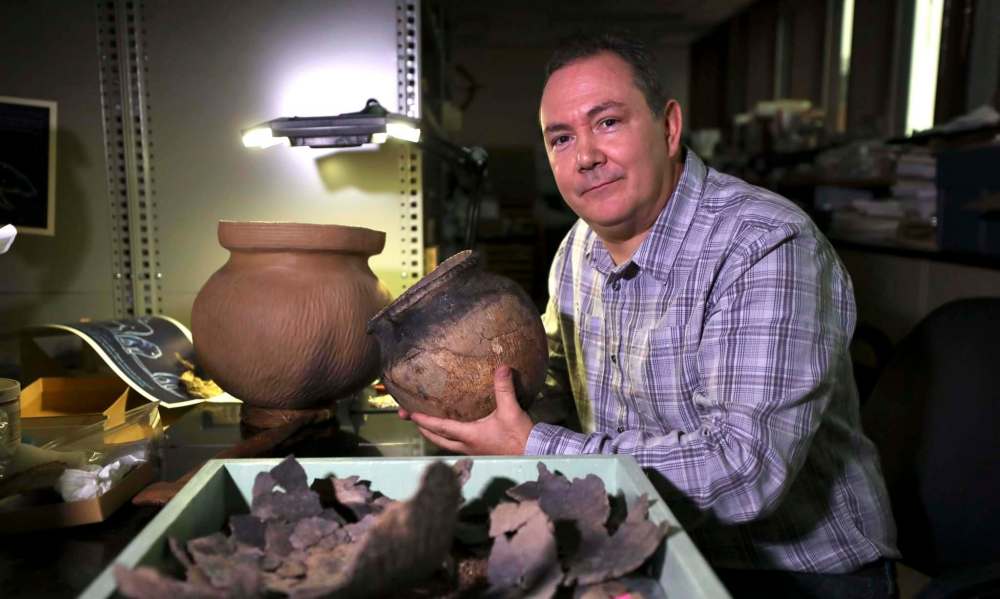

“From just two digs at the Forks we found over seventy pots from at least nine different Indigenous nations from all four directions,” Kevin Brownlee explains to me, “all of which were left here around 1285. These finds just scratch the surface – there are probably more.”

Brownlee is Cree (with ancestral ties to Norway House) and is curator of archeology at the Manitoba Museum. He helped build, research and install the section entitled Indigenous Homelands in the museum’s new History of Winnipeg exhibit.

Here, visitors can see shards of clay pottery from nine different nations that met at Nistawayak and learn about who the people were and how far they came to meet in 1285.

“Can you imagine the negotiations, ceremonies, and diplomacy needed to come to an agreement amongst 10,000 people?” Brownlee asks me. “The 1285 treaty is a testament to Indigenous governments and the political saavy and talents of our ancestors.”

To understand this story, though, you have to understand how these territories in 1285 were in crisis.

From 1150 onwards, along the Mississippi River there was what scientists call a megadrought (a period of extreme dryness) resulting in scarceness of food and incredibly harsh winters throughout the northern hemisphere. This resulted in cataclysmic shifts amongst Indigenous communities here – manifested in struggle, starvation, and strife.

At the end of the Mississippi River were Indigenous nations like the Cree, Anishinaabeg, Lakota, and Dakota, which all began to fight over rapidly depleting resources. Evidence suggests some of these Indigenous nations even began building fences and patrolling lands to stop raids and assert claims over food sources.

Instead of relying solely on hunting and growing food, trading centres like the Indigenous city of Cahokia (in today’s Illinois) – larger than London, England at the time – became crucial to support communities in these parts. These spaces became international trading networks where news and technology was traded as much as food and resources.

By the late 12th century, it was clear to the Cree and Lakota (also known as Assiniboine) – the primary nations who inhabited Nistawayak at the time – that something had to be done. A meeting was called in 1285 for this place.

“The lobbying, arguments, and gifts must have gone on for years beforehand to convince everyone to travel literally for days to come here,” Brownlee says. “The 1285 treaty is a story that does not just begin with the meeting.”

This explains why there is so much evidence of ceremonies at the Forks – particularly of feasts, fire hearths, and objects like pipes.

Much of this is centralized on what Brownlee calls the Peace Village Meeting Site – which begins at the entrance of what is now Shaw Park, southeast down Pioneer Avenue to the Canadian Museum of Human Rights, then southwest to the train tracks (called the Parcel Four parking lot) and back again – spanning a huge rectangle.

Last summer, the City of Winnipeg performed archeological digs in this area, finding some of the richest and most condensed area of fire hearths, fish bones, and pottery in Winnipeg history.

“It’s clear that the Forks was one of the most important political spaces in North America,” Brownlee explains, “and the evidence is in the ground and what we pull out of it.”

The truth is in the stories Indigenous peoples tell as well. The science just has to catch up.

Niigaan Sinclair is Anishinaabe and is a columnist at the Winnipeg Free Press.

Niigaan Sinclair is Anishinaabe and is a columnist at the Winnipeg Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Monday, November 25, 2019 8:48 PM CST: Fixes typo that Margo found.