Canada: It’s complicated Monday's election results highlight our deep regional divisions and long-held resentments, but separate? From each other? After all we've been through? And go where? It's getting cold out there!

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 24/10/2019 (2240 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The morning after the election, while toxic fallout scorched the political post-gaming and most Canadians were trying to move on with their lives, Brian Pallister did the best thing he could’ve done, which was get very, visibly annoyed.

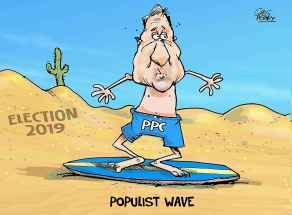

At an event that day, the Manitoba premier was asked about the western separatist sentiment that exploded in the minutes and hours after the election, organized loosely under the remarkably unimaginative moniker Wexit, flames fanned mostly by angry voters, with help from a few politicians.

On the same day, Saskatchewan Premier Scott Moe penned an open letter to Ottawa demanding a “new deal with Canada.” Alberta Premier Jason Kenney disavowed separatist ideology — “landlocking ourselves through separation isn’t a solution,” he said — while pledging to open a public forum to hear those frustrations.

But Pallister, on the eastern edge of the blue wave that swept over the Prairies, wasn’t willing to play at all.

“I listened to this from Quebec for years, and I don’t like listening to it from western Canadian friends of mine,” he said, audibly perturbed. “So no, I’ve no time for that kind of thing. If we’re going to make the country work, we work together on it. We make a commitment to it. It’s a relationship.”

He’s been married 35 years, he added. That didn’t happen by threatening to leave the marriage every week.

This was, as a number of observers pointed out, politically savvy on several fronts. At home, Manitoba is not Alberta or Saskatchewan, and our politics is not the same. Flirting with separatist feeling goes over better in Calgary than it would in Winnipeg; for his own party’s electoral hopes, Pallister is smart to stay out of the fray.

“If we’re going to make the country work, we work together on it. We make a commitment to it. It’s a relationship.” – Premier Brian Pallister

Meanwhile, on the national stage, the dented Trudeau government will be looking for Prairie partners. As the public post-election discourse devolves into chaos, Pallister is wise to signal he’s open to moving forward. That’s good for Manitoba, and the wave of national praise that followed his comments showed why.

Still, none of those goals demanded the response Pallister ultimately chose. He could have stayed out of the debate entirely, making himself as scarce as he did during the federal campaign. He could have ducked the question, or waved it away; that he conveyed his irritation with the subject spoke volumes.

What he said in those words, without explicitly saying it, is that these are dangerous games. The rhetoric of secession is poisonous, even if not now the dominant feeling; in Alberta, nearly 70 per cent of respondents in a recent poll said they sympathized with separatist sentiments. But less than a quarter said they’d actually vote to leave.

So there is no question that a fire of separatism has been lit, though it’s too early to say how seriously it should be taken. It is, for now, a movement stoked by bumper stickers and online petitions, and by a constellation of accounts on Facebook and Twitter bellowing that it’s time for the western provinces to go their own way.

Some of these accounts are almost certainly fakes, made to sow seeds of division. Others ostensibly belong to real people, faces hidden behind a maple leaf avatar, an angry song of secession from the same folks who very recently harangued opponents for being insufficiently patriotic and wanted to hang Trudeau for treason.

Many of those voices have a wide spread. On Twitter, former National Hockey League player Theoren Fleury announced that Canada now has a “dictator in power” in its wounded minority prime minister; he then began furiously retweeting separatist statements, including one user’s pledge to “die fighting standing for the West.”

Hey everybody get your unpopular Liberals tweets in tonight because tomorrow we will have a dictator in power. Buckle up it’s going to be a very different Canada tomorrow morning. We’re done.

— Theo Fleury (@TheoFleury14) 22 October 2019

What that would actually look like is still unformed and fuzzy. On Twitter, many separatists spoke of their movement as encompassing just Alberta and Saskatchewan; others included Manitoba. When an explanation for the latter was needed — how did we get wrapped up in this? — they gave a practical one: we’d bring a saltwater port.

(On that note, you’d think that Albertan separatists playing Build-A-Country would be more sensitive to seizing a province for its resources, given the source of their own frustration with Confederation. Then again, perhaps self-awareness isn’t their forte.)

Will this movement gain momentum, or will it sputter out? This much is certain: the obstacles to secession would be enormous. For starters, even if it became the dominant popular sentiment — and that’s a big if — the Prairies are all treaty land. Good luck untangling that legal question.

If you thought Brexit was bad…

Canada is, everyone agrees, an impractical country, a vast assemblage of territories with little to bind them, save for the force of the calculating colonial will that first drew them together.

For now, let’s set aside the details and consider a different question. To entertain the idea of a hypothetical Canada without the western provinces, we should first understand what Canada is with them. Not in the economic sense or the political one, but in the more nebulous sense of meaning: what is Canada, really?

This has always been a difficult question, sometimes explored as effectively by poets as by historians, and resisting most easy answers. Canada is, everyone agrees, an impractical country, a vast assemblage of territories with little to bind them, save for the force of the calculating colonial will that first drew them together.

The country has not, historically, been bound by any great unifying mythology, as America has been. There is no real Canadian equivalent for Paul Revere’s ride, for the tea in the harbour; this is arguably for the best, as national myths of this kind aggressively obscure the ugliest forces of history. On that front, we have enough problems already.

But the absence of those myths exposes what Canada lacks. It does not have deeply resonant shared cultural rhythms, as in somewhere such as Japan; instead, it sought to obliterate the Indigenous traditions that belong to these lands. Nor does it have a long drumbeat of national history to explain itself, as with the United Kingdom.

Instead, the concept of what Canada is, and what makes someone a Canadian, is most often described by the quirks of Canadian life, even when they are tied to one place or one time and unequally distributed. Under this light, Canada is defined by knowing the words to the Log Driver’s Waltz and the kickers of Heritage Minutes.

The truest and most enduring story of Canada is the simplest one, and unvarnished: we are all stuck here together.

Yet there is a silver lining here. Without any sweeping national myth to define us, our self-reflection can be honest. The truest and most enduring story of Canada is the simplest one, and unvarnished: we are all stuck here together.

It’s not a noble truth, just a fact, one that’s been better for some and worse for others. It’s a fact that has brokered progress at the same time as trauma. A fact that has driven great strides and also great tension. We carry on only because we have to, because that’s where history has brought us, the juncture at which we’ve all landed.

Or, in other words, and to paraphrase Pallister: if we’re going to make it work, we’ll have to do it together.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.