West tells Quebec to drop religious-symbols ban

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 09/10/2019 (2258 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

GATINEAU, Que. — Hanaa Mouloudi wants to be a teacher, a goal she’ll have to leave home to pursue.

“I’m going to move, because Canada is more than just Quebec,” said Mouloudi, 16, wearing a black headscarf.

As Quebec’s secularism law, Bill 21, looms large in the federal election campaign, a growing chorus of western Canadians are asking political leaders to take a stand against the law.

It’s given some hope to Mouloudi, a Grade 11 student who plans to apply for teachers’ college next year, even though no school in Quebec will hire her.

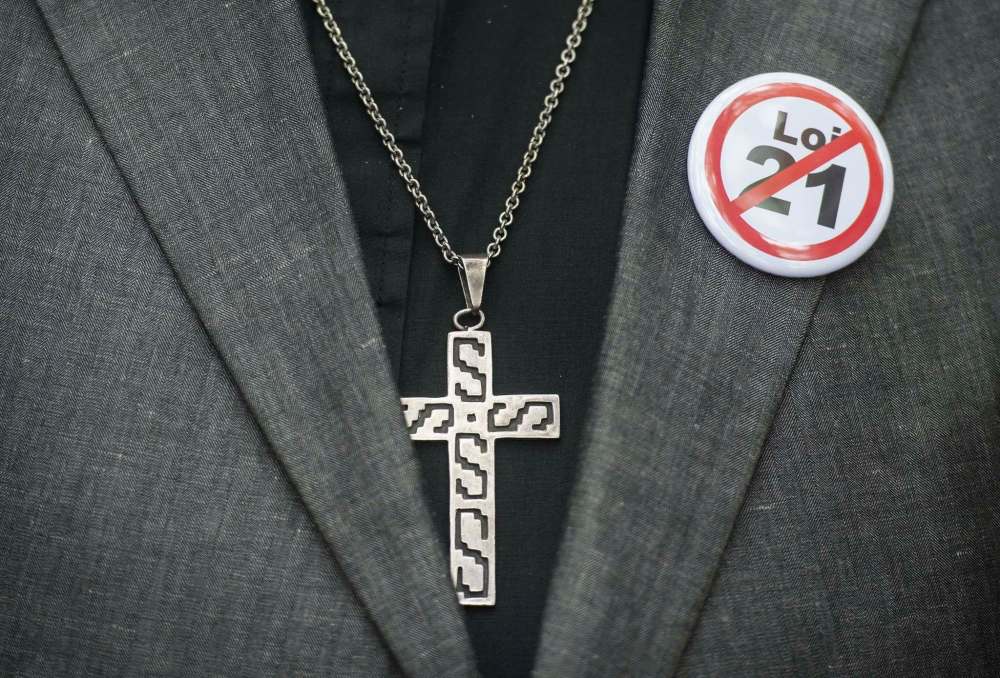

The law, which the government of Premier François Legault passed in June, bars anyone in a public-service position of authority, including teachers, judges and police officers, from wearing religious symbols.

Those who want such jobs must remove their hijabs, turbans and kippas.

“I’ve never been anyone’s slave, so I’m not going to just obey what [Premier Legault] says, to take off my veil, in order to have a career,” Mouloudi said in French. “It’s not going to happen.”

“When other provinces speak out, it will have a really positive effect, because Mr. Legault will see that we’re not all alone,” she said at a Sunday protest against the law, within eyesight of Parliament Hill.

Since the law came into effect, the National Council of Canadian Muslims has documented an uptick in hate incidents in the province, while far-right groups have leveraged the labour department’s workplace-violation hotline to report employees they suspect of breaking it.

“This law has put oil on the fire to increase the racism that is already there,” Mouloudi’s father, Rabah, said.

In July, Manitoba Premier Brian Pallister decried Quebec’s “clothing police” for causing an “erosion of rights” and a culture of fear. He’s tried in vain to get other premiers and national leaders to contest the law.

Parties mum on challenging Quebec law

OTTAWA — Bill 21 came up numerous times in Monday’s federal leaders debate, despite little actual response from Ottawa.

OTTAWA — Bill 21 came up numerous times in Monday’s federal leaders debate, despite little actual response from Ottawa.

In the debate, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau boasted he had left the door open to Ottawa intervening, even though he has pledged not to act until courts rule on existing appeals from groups within the province.

NDP Leader Jagmeet Singh has taken the same approach but has been much more coy, likely worried about scaring away voters in a province where the law is widely popular.

That’s hypocritical to Hanaa Mouloudi, who argues Singh should pledge to intervene in court. “It really disappointed me. You must feel the same way I feel, because you also wear a religious sign,” said the 16-year-old.

The Quebec legislature had to invoke the Charter’s notwithstanding clause to get Bill 21 passed, sidestepping rights to equality and freedom of religion. The law doesn’t apply to actual articles of clothing: a public servant can don a headscarf, as long as it’s not worn for a religious reason.

The law also freezes public servants into their roles, meaning teachers wearing hijabs can’t be promoted to superintendents, and lawyers wearing turbans can’t be made judges.

The Conservatives have refused to say whether they’d challenge the law, while the Greens officially oppose Bill 21, but haven’t said how Ottawa ought to respond.

Mouloudi wants all parties to take a stronger stance.

“Regardless of where you’re from, regardless what religion you are, whatever background you have, you should be concerned,” she said.

—Dylan Robertson

Two months ago, Manitoba’s civil service reached out to professional organizations and unions in Quebec, encouraging French-speaking bureaucrats to head west for jobs serving Franco-Manitobans in fields such as education, engineering and agriculture.

Since then, Pallister’s office says school divisions have been attending job fairs for teachers in Quebec.

Last month, Calgary city council passed a motion formally condemning the law, with the city’s mayor Naheed Nenshi comparing it to measures taken in Saudi Arabia, while a grassroots group launched in Ontario last week called Canadians United, asking members of the public and federal candidates to take a public stance against it in an online petition.

“Religious discrimination isn’t an isolated issue, and wherever it’s taking place, we should take a stance against it,” said organizer Nita Kang, who lives in Mississauga, Ont.

“If we accept it in Quebec, what’s to say another province may not try to put in the same type of bill.”

In Montreal, activist Hanadi Saad said she suspects some from Western Canada are playing into anti-Quebec sentiment in opposing the law, but on the whole, it’s welcome, she said.

“It gives hope to the minorities,” said Saad, founder of the group Justice Femme, which has sent anti-Bill 21 buttons to groups across Canada holding small rallies against the law.

“It’s the first time in my life that I’ve said I’m ashamed to be a Quebecer. We need to let the rest of Canada know what’s going on,” said Saad, who does not wear a veil.

The law is popular in the province; a poll last November found 70 per cent of Quebecers support barring religious symbols from the judiciary and 65 per cent want the law applied to teachers. In the Prairies, a slight plurality oppose Bill 21.

Adam Ami, an engineer born in Tunisia, said he left Switzerland for Quebec two decades ago because it’s a more open-minded society. He’s glad Manitoba is speaking up.

“This model of government doesn’t apply in a modern-day, pluralist society. They have to respect the basic freedoms that other generations have fought for,” he said at a Sunday protest.

Others want Western Canada to butt out.

“Canada is entitled to its own values, as well as Quebec is entitled to its own values,” Bloc Québécois Leader Yves-François Blanchet told the Free Press at Monday’s leader debate.

“We should be friends and partners, [instead] now we have to fight over an issue which should belong to the nation of Quebecers.”

The law, and various provincial measures to slow immigration, could stall Quebec’s juggernaut economy, which largely absorbed asylum claimants who have arrived on foot in recent years, because so many jobs need to be filled.

“I know that I have potential. In the end, I’m not the one who’s going to lose out. It’s going to be Mr. Legault and the lack of teachers here,” Mouloudi said.

dylan.robertson@freepress.mb.ca