Despite hardships, homeless camps continue on own terms

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then billed as $19 every four weeks (new subscribers and qualified returning subscribers only). Cancel anytime.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 02/10/2019 (1814 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Klarrisa Muswagon lives just off Wellington Crescent, where some of Winnipeg’s wealthiest denizens reside. But she doesn’t own a million-dollar mansion.

Her home is a bright-orange Coleman Bayside six-person tent beneath the Maryland Bridge.

The 24-year-old has been set up there since June, spending much of her time writing journal entries and reading the newspaper. Her bed’s headboard is the concrete base of the bridge above her. Keeping her warm Thursday morning were a few woven blankets and a small fire flickering not far from the lip of the Assiniboine River.

A day earlier, a much larger camp under the Osborne Street Bridge was mostly engulfed in flames, an accidental fire believed to be caused by a candle. As the October air cools toward freezing, the Osborne campers pledged to rebuild and Muswagon said she intended to stay until she found a more permanent dwelling.

“To me, it feels like camping,” said Muswagon, wearing a T-shirt and basketball shorts.

For various reasons, some people experiencing homelessness in the city prefer to stay outside, creating shelter on their own terms rather than seeking out a spot in a traditional shelter environment. That won’t change this winter, even if tents like Muswagon’s are built to be used the other three seasons.

For many in her position in Winnipeg, the opportunity to find alternative living situations are sparse. Last year’s street census — which counted people experiencing homelessness or housing insecurity in a single point in time — found 204 completely unsheltered individuals, 392 using the emergency shelter system, and 895 with provisional accommodations in hospitals, jails, motels and hotels, and couch-surfing.

According to Statistics Canada, there were only 435 shelter beds in the city, as of 2018.

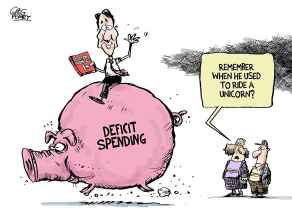

For those looking to rent, the situation is equally precarious. The benchmark for affordable housing is spending less than 30 per cent of income on housing, but the 2019 Canadian Rental Housing Index showed the lowest quartile of Winnipeggers (who earn less than $22,591 annually) spend 67 per cent of income on rent and utilities.

Kirsten Bernas, chairwoman of the Right to Housing Coalition, said assistance available generally doesn’t cover living costs.

“Employment and Income Assistance provides $576 per month for rent, but the average bachelor suite rents for about $700,” she said. “This can put them in an ongoing state of crisis to meet their basic needs.

“One alternative can be to go into subsidized housing. But there is a huge wait list for Manitoba Housing, for example, and people who are experiencing homelessness will require housing more urgently once the weather turns,” she said Thursday.

“The clear need is for (income-geared, affordable) housing,” said Kristiana Clemens, manager of communications and community relations for End Homelessness Winnipeg, the organization which, along with Main Street Project and City of Winnipeg, has been tasked this year with managing the homelessness situation.

“Having more emergency shelter spaces will also help to create more options, but ultimately, people need access to addresses and homes.”

Since July, when a request for proposal that would have resulted in the dismantling of temporary homeless encampments was cancelled by the city, all reports of homeless encampments in Winnipeg have been triaged through 311 to the Winnipeg Police Service (if public safety is threatened) or Main Street Project, a city spokesperson said.

Main Street’s outreach team has been busy, said Cindy Titus, communications and fund development co-ordinator. Workers had been visiting the Osborne encampment, and its outreach van has been dispatched across the city several times each day to check on the well-being of residents of a number of camps, she said.

“I think an important thing to understand… is those individuals are a tight-knit community who look out for each other,” Titus said, referring to the Osborne bridge camp. “They’re going to be coming together as a community to determine what their next steps are, and we will be providing whatever support they need.”

As temperatures drop, that support becomes even more vital.

Frank, 51, lives across the river from Muswagon, beside the First Unitarian Universalist Church of Winnipeg.

He has started to light a small, sealed barbecue at his campsite to keep warm. It rests on a marble slab to prevent it from burning the ground, with a steel heat-shield in front to keep it contained. He sleeps next to a pot of water and one of sand, just in case.

The fire under the Osborne bridge brought up bad memories: in July, his camp was torched, Frank said, and he had to start from scratch. But Frank said he’ll still do what he can to stay safe, warm, and alive.

“Everyone thinks everybody out here is either a junkie or a thief. We’re not all junkies, and we’re not all thieves,” he said.

When asked if he feels safe, Frank laughed. “Hell, look at these four walls. Nylon.”

Nothing’s permanent out here, he said.

ben.waldman@freepress.mb.ca

Ben Waldman

Reporter

Ben Waldman covers a little bit of everything for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.