Long-lost book about 1919 strike finds new life

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 26/04/2019 (2421 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

For years, Molly McCracken knew about the book manuscripts her late mother had left, though she’d never had time to read them. They were tucked away safely in the University of Manitoba’s archives where Melinda McCracken had placed them, along with some of her diaries, short stories, and letters from notable people.

The manuscripts might have stayed there, mostly forgotten. But in 2017, the labour community in Winnipeg began talking about plans to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the 1919 general strike; as Manitoba director for the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, Molly often found herself at the heart of those discussions.

Her thoughts turned to one of the unpublished books her mother, a prolific writer, had left behind. Papergirl, it was called, and she knew it was centred around the strike. So she went to the U of M to look at the manuscript, and as she started to read, echoes of Melinda’s unmistakeable voice came rushing back into her mind.

“She just springs right off the page,” Molly says, chatting at a Portage Avenue cafe earlier this month.

Now, nearly four decades since Melinda started writing Papergirl, and 17 years since she died, the book is at last coming into the public light. In collaboration with Halifax writer Penelope Jackson, and published by local imprint Roseway Publishing, the book will hit store shelves next month in time for the anniversary of the strike.

The book, which is targeted at middle-grade readers, explores the strike’s history through the eyes of Cassie, a spirited 10-year-old girl who volunteers to distribute the strikers’ newspaper at Portage and Main. (There’s also a companion teacher’s guide, for educators who wish to use the book in their classrooms.)

As Cassie navigates the surging strike movement, she also faces the hunger that gnawed at poor workers, and mounting pressure from authorities. It is a story about working-class life in Winnipeg, and about justice. It is also a labour of love — both by the woman who first wrote it, and the daughter who helped give it renewed life.

“My grandmother was a very good storyteller, and she would talk about the horses bringing the ice for the icebox, and the milkmen, and the baking powder biscuits that were my grandmother’s specialty. That’s what they talked about with me around.”

– Molly McCracken

Melinda started writing Papergirl in 1980. She was an accomplished writer by then, having written for the Globe and Mail, Maclean’s Magazine and Chatelaine. Her debut book, Memories Are Made of This, had been published in 1975 to some acclaim; it captured her impressions of growing up in the Winnipeg of the 1950s.

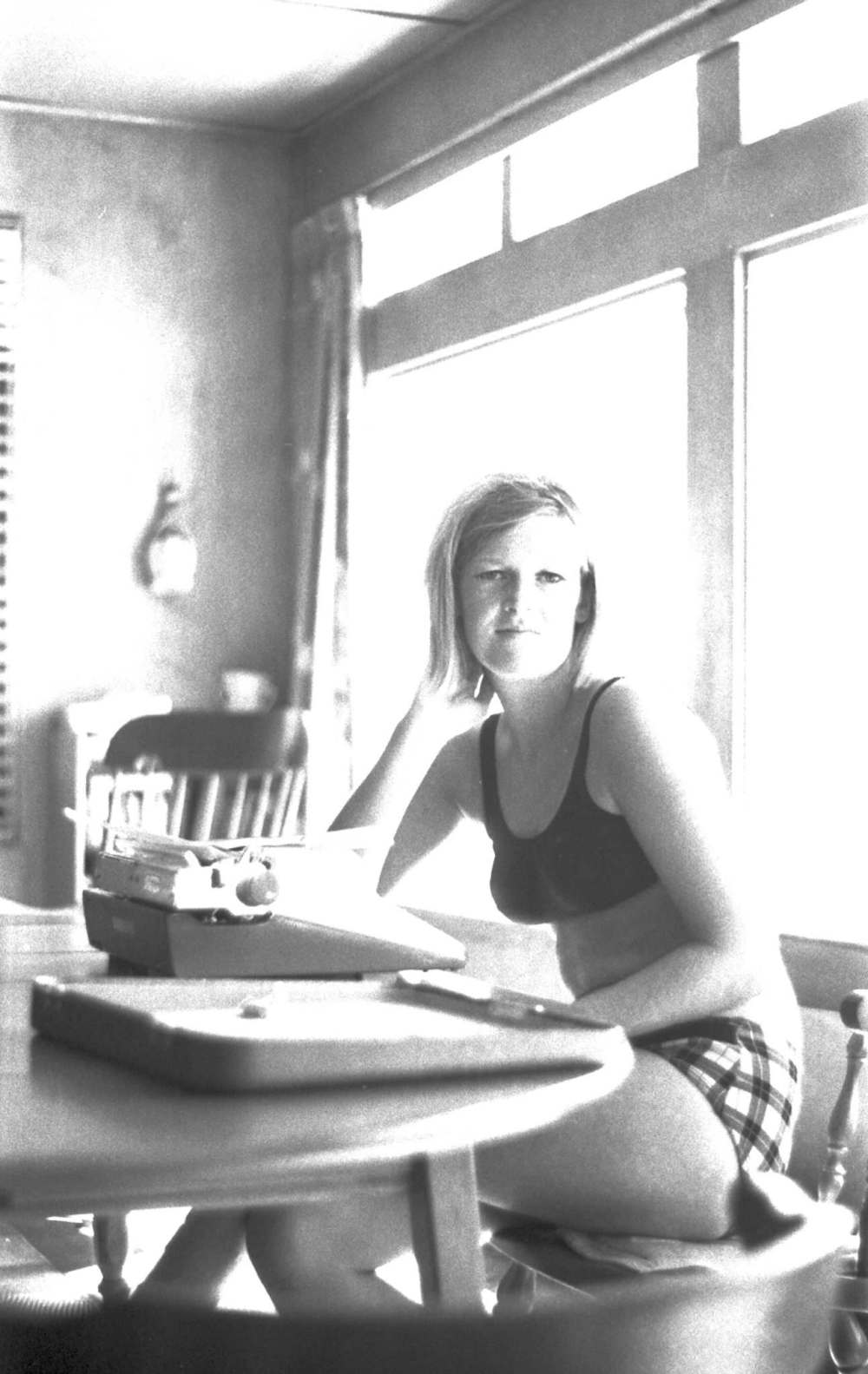

For two years, Melinda worked on Papergirl, fingers clacking away at the typewriter she kept in the basement of the Riverview home she shared with her parents and daughter. Today, Molly can still remember how her mother would pepper her grandmother with questions about what everyday life was like in the early 20th century.

“My grandmother was a very good storyteller, and she would talk about the horses bringing the ice for the icebox, and the milkmen, and the baking powder biscuits that were my grandmother’s specialty,” says Molly, who was about seven years old when her mother was writing the book. “That’s what they talked about with me around.”

Those little details, passed from mother to daughter, made Papergirl sing. The protagonist is named after Molly’s great-aunt; those baking powder biscuits make an appearance early in the book, when Cassie’s mother bakes massive batches to feed striking workers at a soup kitchen run out of the Strathcona Restaurant downtown.

Despite the care she took in writing it, the book never took off. After finishing Papergirl in 1981, Melinda shopped the book to publishers, but found no takers; she tucked their rejection letters next to the manuscript. Eventually, she set it aside and turned her focus to shorter pieces, including columns for the Winnipeg Free Press.

Two years before she died of breast cancer in 2002, she donated the Papergirl manuscript to the U of M, along with 20 boxes of correspondence, clippings and other material. It remained there until Molly unearthed it; what struck her most, she says, is that even though so much time had passed, the book’s message remained timely.

For instance, she points to how the book centres on strong female characters. In the book, Cassie looks up to Helen Armstrong, who led the Women’s Labour League and was famed as a fearless orator and organizer. (Armstrong was the subject of a 2016 documentary by local filmmaker Paula Kelly, called The Notorious Mrs. Armstrong.)

And in the 10-year-old protagonist herself, Molly sees echoes of modern youth leaders such as 16-year-old Greta Thunberg, a Swedish activist who turned her school strike for climate action into a global phenomenon. Papergirl may be historical fiction, and written decades ago, but its spirit hums in tune with today’s pressing issues.

“There’s a thread of girls leading climate action movements and other movements in our world today, and we need their leadership and their voices, so I think it hopefully inspires other girls to get involved,” Molly says. “Girls’ voices, there’s more space for them and we’re listening more, and that’s really exciting.”

Now, Molly is looking forward to having that new generation of readers discover her mother’s voice. Writers put so much of themselves into their work, and it’s rare to have a piece that languished for so long get its chance to shine. Not long ago, she dreamed that her mother came to give her a hug. In the dream, Melinda was beaming.

“I think she felt a little under-appreciated in her lifetime, so it’s nice to have her work come to light,” Molly says.

Melinda McCracken’s family will host a book launch for Papergirl on at 2 p.m. on Sunday, May 5, in the atrium of McNally Robinson Grant Park.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.