Tina’s tragic life laid bare

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 12/03/2019 (2465 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

SAGKEENG FIRST NATION — It feels like every reporter in Winnipeg is here, and every television camera for miles. They arrived after sunrise, drifting into a gymnasium painted in bright colours, air thick with the scent of sweetgrass and the ghost of a tiny, soft-spoken child who once must have scampered over its floor.

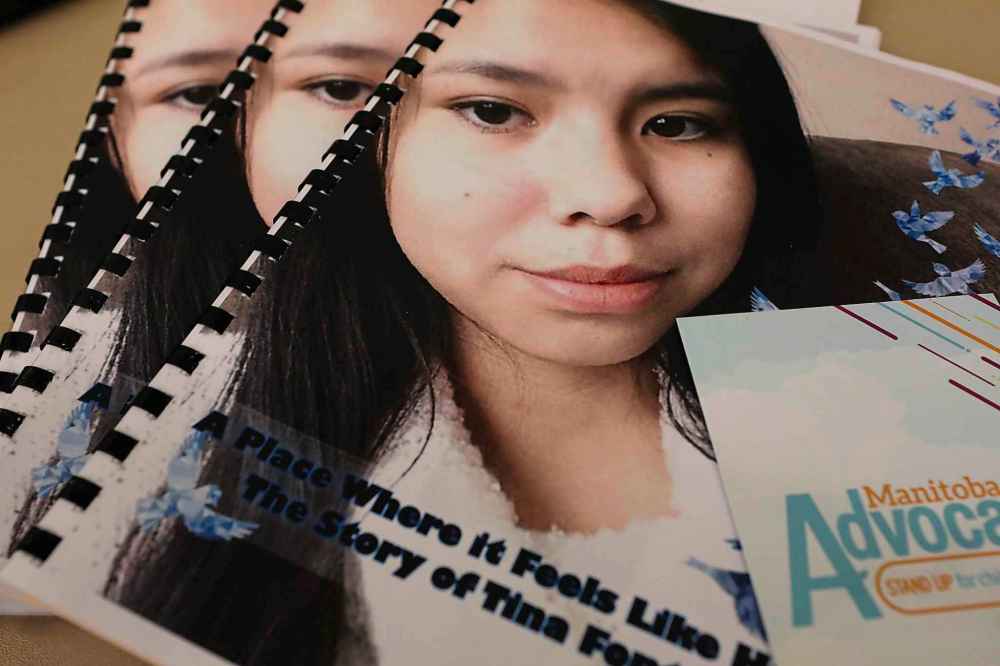

By now, her name has crossed oceans. For years, Sagkeeng First Nation Chief Derrick Henderson fielded calls about Tina Fontaine “from all over,” he says, from media outlets across Canada and beyond. In death, her name became a torch, a light on all the evils that lurk in the shadows and steal life from Indigenous women and girls.

Countless Manitobans embraced her then, after she was dead. We wept for her, and rallied for her, and watched the trial of the man accused of killing her with anxious attention. We gathered again when he was acquitted in February 2018, holding her name close, trying to breathe justice into existence by the power of memory alone.It was not love that failed Tina– that, she always had. It was systems that failed her, and that story is not new.

She never asked for any of this, though. She was just a child, hurting, searching for a place to fit in.

Despite all of this, despite the trial and the rallies and all the words written, we still don’t know much about how she died. What is sadder than that, is that we heard almost as little about how she lived, about what chasms opened up underneath her feet that sent her on that inexorable fall to the streets, and the river.

That is the gap that Manitoba Child Advocate Daphne Penrose’s new report hopes to fill in. At 115 pages, it is split between a retelling of the pivotal events of Tina’s 15 years of life, and a set of recommendations. And this is the least we can do, to bear witness: open the report, which is publicly available online. Read it. See how far you get before you start to cry.

In the Sagkeeng gymnasium, I make it as far as page 39. At that point, the report picks up the short thread of Tina’s life on the afternoon of July 17, 2014, when she is is released from a short-term detox, picked up by a child and family services worker and stashed in a downtown motel.

No plan was made for Tina then, the report notes. There is no assessment of her situation, and no supports given.

Right then, in full view of the people charged with protecting Tina, her life is coming unravelled. Over the next few weeks, she will bounce in and out of shelters; one month later, on Aug. 17, 2014, a recovery team will pull her body from the Red River, wrapped in a Costco duvet and weighed down with stones.

But that is the end of Tina’s life, and the advocate’s report concerns itself mostly with the beginning and middle. How she was born to struggling parents, and raised from age five by her great-aunt, Thelma Favel, who loved Tina and, limited by a customary guardianship not adequately recognized by authorities, did the best she could for her.

It was not love that failed Tina — that, she always had. It was systems that failed her, and that story is not new. Mostly, those failures broke loose after Tina’s father, Eugene Fontaine, was murdered in 2011. The loss seemed to send Tina reeling; as time went on, she started skipping school, began dabbling in drugs, ran away from home.

Yet none of the authorities in Tina’s life seemed to recognize the urgency of her pain. In 2013, victim services told Favel that the family wasn’t eligible for wage compensation, since the kids hadn’t been living with their father and he hadn’t been working; they did not mention, in that rejection letter, that the family could access counselling.

In fact, nobody in positions of authority moved quickly to get support for the girl. When a CFS agency finally did refer Tina for counselling in the summer of 2014, the family couldn’t go: child welfare workers had made the initial arrangements for Beausejour, and they didn’t have a car to drive the 75 kilometres from Powerview.

These parts of the report are painful to read, almost maddening. Over the years, and especially as her life spiralled onto the street, Tina’s case bounced between workers from no fewer than five different child welfare agencies, who sometimes debated who was responsible for her case in an labyrinthian game of back-and-forth calls.

Now you are up to summer 2014 in Tina’s story. Nobody in these pages knows it yet, but the clock is ticking. The thread of her life is fraying: she turns up at youth shelters, finds no beds, leaves. Police find her with a drunk man in a car and let her go. Hours later, she is passed out in an alley. She is taken to hospital, and then to a hotel.

Authorities deliberate what to do with her. Youth workers make conflicting assessments of just how vulnerable she is. Your chest aches to shout at them through the pages, praying for a different ending than the one that is coming, the one we have borne witness to for the last five years running, the one that cannot now be undone.

Someone get her now. There’s no time. Just anyone, go find that girl and take her home.

And then she is gone. She vanishes from the report on her life, as silently as she does from the world.

On Aug. 14, a manager with CFS’s StreetReach program emailed the police missing persons unit, and called Tina’s case “a jurisdictional nightmare with a bunch of different agencies playing hot potato, it’s your case not ours… bottom line is there have been numerous concerns documented in our (CFS) system that this child is being exploited…”

The manager promised that they would start looking for her the next day. By then, it was already too late: she was almost certainly already dead.

Now, it is time for action. The advocate’s report marks the end of what the public will learn about Tina, both her life and her death. With nothing new to say, the media that has peppered Sagkeeng for the last five years will go away. Her name will fall from the headlines, though never from her family or community’s hearts.

In a way, that is a mercy: if the lessons of what failed her can be learned through this report, and changes enacted through careful consideration of its recommendations, then her memory can at last be given to rest. And then, she can at last be what she ought to have been: just a child, just loved, and forever missed.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.