Shivering in the shadows When temperatures dip dangerously low, Main Street Project's van patrol is hyper-vigilant in ensuring the homeless are accounted for

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 01/02/2019 (2505 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

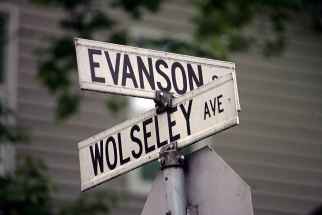

In the back lane, a sallow light gives shape to the shadows, casting a dim pall over where the man is bundled in a black jacket, rummaging in a dumpster. Robin Eastman spies him and taps the brakes, slowing the van to a stop.

As tires crunch old snow, the young man looks up. He spies the van, with the familiar Main Street Project logo emblazoned on its white flank, and his face softens with a pleased recognition. He ambles towards the vehicle.

Outreach worker Emmanuel Olatubosun rolls down the passenger window. A frigid wind breathes into the van, chasing away its warmth. The bitterest edge of the polar vortex has faded from Winnipeg, but it is still too cold.

“Are you doing OK?” Olatubosun calls out.

The man nods, and they start to chat. Olatubosun asks the youth what he needs and, for a moment, rummages through the containers near his seat. He pulls out a thermos of hot coffee, a sandwich, a pack of clean needles.

“We have blankets today,” Eastman says, leaning towards the window.

Outside the van, the man’s eyes light up. Blankets are a precious commodity on Winnipeg streets, and when the Main Street Project’s patrol van has some in stock, they go fast. The man accepts a hand-knit patchwork blanket.

This is what most of the van’s clients ask for, Eastman explains later. Blankets or socks to layer on in this viciously cruel weather. Even just a cup of hot coffee, on some nights, can be the small mercy that makes the night livable.

“We’ve been out here to look after those people, people who cannot take care of themselves, and supply them with all these needs,” Olatubosun says, gesturing at the nearby containers of warming gear. “I think we’re really helping.”

In the backseat, there is a large plastic shopping bag, overflowing with gloves and colourful fleece mittens. It looks like a lot, Eastman says, but they give out dozens of pairs every night. These will all be gone by time dawn breaks.

It’s Thursday night, just before 8 p.m., and the van has already been combing Winnipeg’s streets for four hours. It’s quiet tonight, Eastman says. So far, the van has encountered only a handful of people that need its many services.

She and Olatubosun decide that’s a good thing. Hopefully, it means most of the people they serve found shelter.

It’s not always like that. There are nights when the van carries not only blankets and gloves, but vulnerable people seeking a ride to Main Street Project’s Martha Street shelter. Van workers offer that to anyone they think is in need.

Last week, Eastman spied one of the shelter’s regulars on the street. He flagged the van down, limping over on frozen feet. They took him to the Salvation Army, where he was staying; without them, he might not have made it.

Still, many folks they meet choose to stay on the street, preferring to hunker down for the night in ATM vestibules or bus shelters.

“They’re so used to being situated where they are,” Eastman says. “So we respect their wishes. We don’t push them. It’s something they’re used to, right? It’s become their norm. They’ve been homeless for so long, that’s all they know.”

For those people, in this cold, the van patrol’s meandering route through the city can weave a safety net of survival.

The winter is a divisive killer. It preys on the most vulnerable, those with the least access to shelter. In the U.S. Midwest, at least 21 people froze to death last month, as the polar vortex swept over North America. Dozens more were treated for severe frostbite, half of them homeless.

In Winnipeg, it’s hard to know how many people lose digits or lives to the cold. No public agency routinely releases those numbers, although death and injury by freezing is, arguably, a pressing public health concern in a harsh-winter city.

All we know is that these injuries do happen. Just the other week, Olatubosun ran into one of the shelter’s regulars. The man had been stuck out in the cold after using meth, he said; doctors told him he might lose all of his fingers.

This is why the van patrol exists. Every night, its staff have the potential to change the ending to that story — and in fact, this iteration of the van patrol itself stands as a memorial of sorts, to one life that was stolen by the killing cold.

Flashback to December 2016. In downtown Winnipeg, firefighters had been called to help a man and a woman, spotted looking frozen on a night when temperatures fell to -32 C. But when they arrived the pair ran away, possibly hearing sirens and fearing police.

Rescuers soon found the man, dangerously cold and in distress. They could not locate the woman. A few hours later, she was found lying on the ground on Portage Avenue, dead.

At the time, Main Street Project executive director Rick Lees had been lobbying to bring the van patrol back. Lack of funding had grounded the patrol in 2009 and Lees, in his first year at the shelter, was trying to find a lasting solution.

That was easier said than done. For months, Lees wrangled with the bureaucracy that wraps itself around non-profit funding. He believed in the potential of the van patrol program, but convincing others to invest in the effort took time.

Then the woman died in the cold, and Lees decided Main Street Project would find a way to relaunch the van patrol on its own. The shelter already had three Dodge Caravans it used to transport clients to clinics; why not use those?

“I just went, ‘this is ridiculous,'” Lees says. “We had so many people sitting around offices debating the van patrol, and literally it was as simple as saying… ‘We need to get the van patrol on the road. We don’t have time to do recruitment and hiring. We just need to get out.'”

Shelter staff quickly formulated a plan to staff the effort. Within 24 hours, the van was rolling over Winnipeg’s streets.

That move seemed to inspire other area non-profits to make their own bold cold-fighting moves. Soon, the Salvation Army had its own warming van on the streets, a repurposed ambulance that had been languishing in Thunder Bay.

At Main Street Project, funding for the van started to flow in, first by private donation and then in the form of a grant from the federal housing initiative. That allowed the shelter to buy a new van, which hit the streets in January 2018.

The $89,000 van is spacious, custom-built with eight seats, a hydraulic lift and space for two wheelchairs. That’s big enough to meet all of its needs, which are evolving: soon, Lees hopes to bring a nurse on board, to provide services such as minor wound care and rapid HIV testing.

The investment proved worth it. On an average night shift — which runs from midnight until roughly 8 a.m. — the van makes contact with between 70 and 100 people. The response from the community was so strong that staff lobbied for an evening shift, which launched last month and runs from 4 to 11 p.m.

Right now, that evening shift is quieter than the overnight span. Over time, the van’s clientele have learned its night-time patterns; they congregate at places where it frequents, including most core-area 7-Elevens, and rush out to meet it. They are still learning that it’s out earlier in the evening, too.

“Once they know, I’m pretty sure they’ll come to us,” Eastman says. “Right now, we’re just finding them.”

But the van’s success should not obscure one key fact: the city still lacks a comprehensive plan for cold safety. That’s a stark contrast from somewhere like Toronto, Lees points out, where the city itself opened a handful of warming shelters. Here, the work of battling the killing cold is done by private non-profits.

There is hope in that, too. Because what the city’s shelters do well, that larger efforts can’t always do, is build connections with people. On patrol, Eastman greets many of the van’s visitors by name, sometimes expressing surprise at the area she’s found them, far away from their usual stomping grounds.

That’s normal, around Main Street Project. And in weeks like this one, where the cold is so dangerous, it’s vital.

“We know when they’re missing,” Lees says. “We know when they should be in the shelter tonight, and they’re not there. Typically people will start rolling in by 6 p.m. or 7 p.m., and the shelter’s full by 9 p.m., and we’ve accounted for the regulars.

“Then someone will say, ‘Peter’s missing. Where’s Peter? has anyone seen Peter today?'” Lees continues. “And we know their problems, whether it’s schizophrenia or addiction or both. They’ll radio the van and say, ‘Peter should have been there. Can you go find him?'”

This is, perhaps, the most critical part of the whole endeavour. In many ways, all of our chances of surviving in high-risk conditions often comes down to being known. Who will come looking for you? Who claims you as their own? For many of Winnipeg’s most vulnerable people, it is the van patrol.

Back on the streets, the frigid Thursday night is still young. The Jets are playing at Bell MTS Place, where they will soon beat the Columbus Blue Jackets. More than 15,000 people are jammed into one square block, and yet the downtown around it glitters as empty as the wind-blasted surface of some alien planet.

Around the corner from the arena, a man waves the van down. Eastman slows to a stop on the corner, and waits for him to scurry up to the passenger-side window. His cheeks are bright from the wind. He takes a hot coffee, a sandwich, a pair of gloves. Then he waves goodbye, and trundles off.

When he’s gone, Eastman drives away, eyes searching the shadows for the next shape shivering in the cold.

“We do the best we can for them,” Eastman says. “That’s why we’re here, right?”

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.