An open wound, 30 years later Christine Jack's daughter has not – cannot – give up hope she'll get closure about her mother's 1988 disappearance and whether her ex-Blue Bomber father killed her

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/12/2018 (2554 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

When she was 33 years old, Christine Jack vanished, leaving those who loved her with a question that has haunted them for three decades.

The question of what, exactly, happened to the wife and mother a week before Christmas 1988, rattles through their minds in search of an answer they never get.

For them, the pain is always there; the sensation of what’s been lost, and what could have been, lingers like a phantom limb.

The disappearance of a loved one, without the closure — however terrible in its own right — that comes from the discovery of their remains, is a horror unimaginable to those who’ve not lived through it.

At some point, however, there is another question that stirs in their minds: How long should we cling to the hope, however faint, that one day we might finally learn the truth?

For Kairsten Fatland, one of Jack’s two children, now a year older than her mother was when she went missing, the answer is a simple one.

As long as it takes.

“It’s always hard talking about this,” Fatland says. “The only reason I do it is the chance that maybe there’s somebody out there who knows something and hasn’t spoken out before. Maybe if they see this they’ll come forward with some clue that will lead us to finding her.

“You wonder, ‘What really did happen?’ You go through all those thoughts and all the details, and you pray and hope that someday you’ll get closure.”

On Tuesday, Jack’s family will commemorate the 30th anniversary of her disappearance and presumed death in a mystery that gripped the city for months.

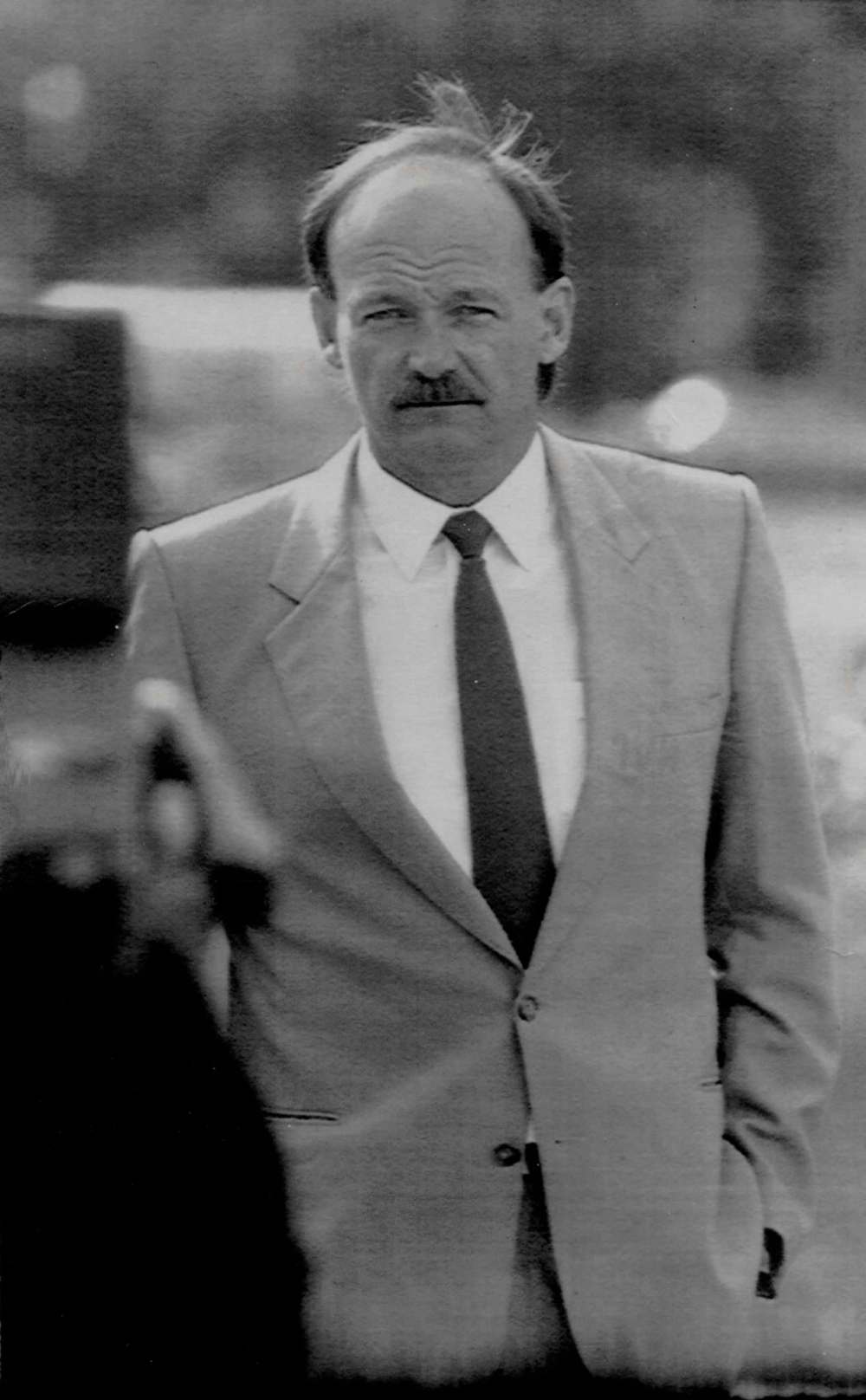

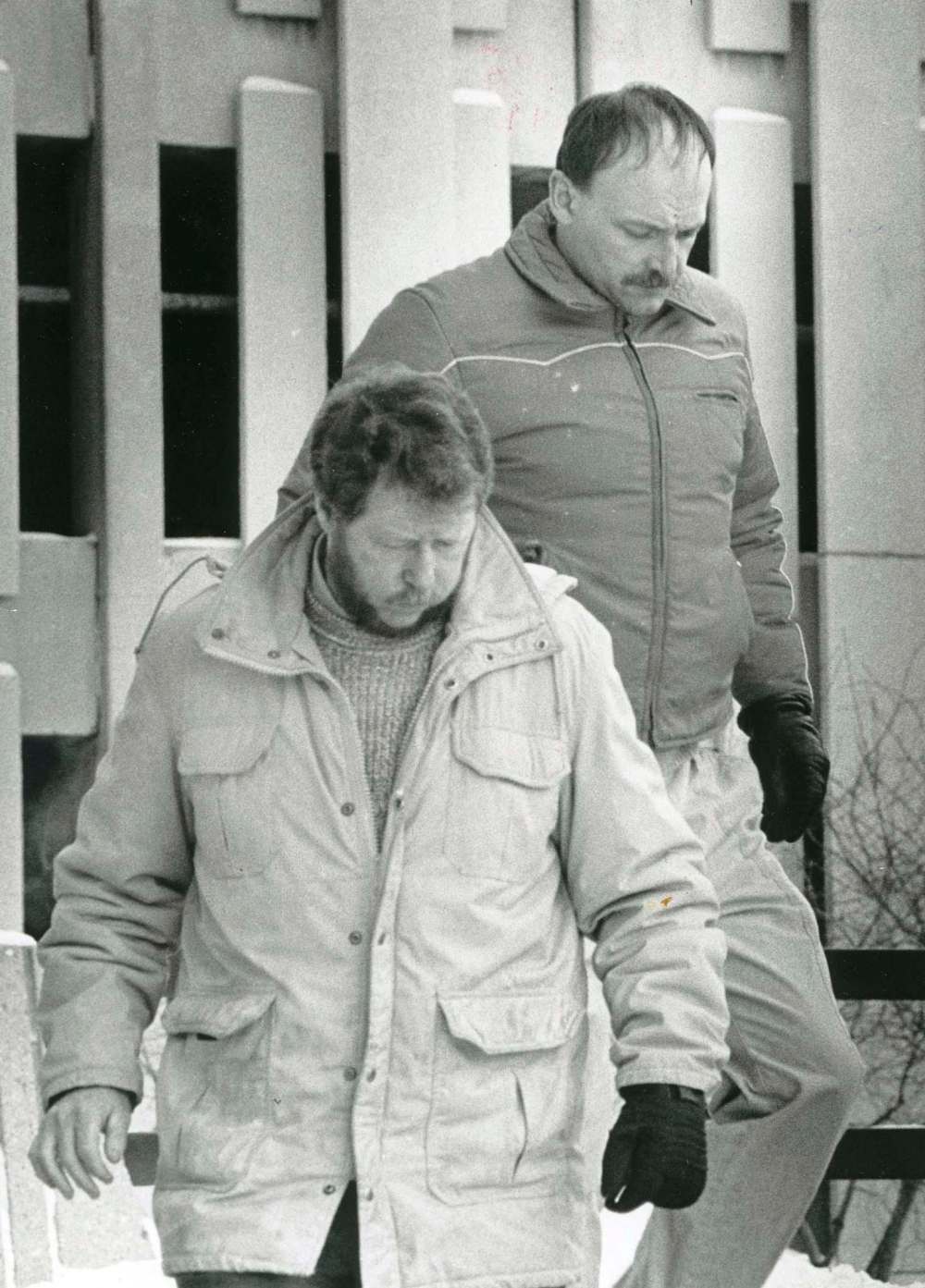

Her husband, and Fatland’s estranged father, former Winnipeg Blue Bomber tight end Brian Jack, has long been the principal suspect.

In total, Jack was tried three times for his wife’s slaying, leading to two convictions: one in 1990 for second degree murder and another in 1995 for manslaughter. But three appeals and a complicated web of legal proceedings later, he walked away a free man in 1997.

Jack has always maintained his innocence. But like many others, Fatland believes he is the only person who can provide the closure she desperately seeks.

“There was just so much evidence that pointed in his direction. I wish he could find it in his heart to help us find her remains, or give us a clue, or tell somebody to tell somebody where she is,” Fatland says.

“It’s not even that we want him to be in trouble. I think we’re past that. We just want closure. We want to give her the proper burial that she deserves.”

In December 1988, Christine told her friends that she was at the end of her rope and planned to leave her husband. Their marriage had been crumbling for some time.

Brian Jack was unemployed and blamed money problems for placing strain on the relationship. A psychologist would testify at the first trial that he’d also admitted to “forcing himself sexually” on his wife.

Three days before she went missing, Christine met with a lawyer to discuss her options for divorce. She also told confidants she was worried about how he’d react when she told him the marriage was over.

Depending on whom you ask and what evidence you consider, one of two things happened on Dec. 17, 1988.

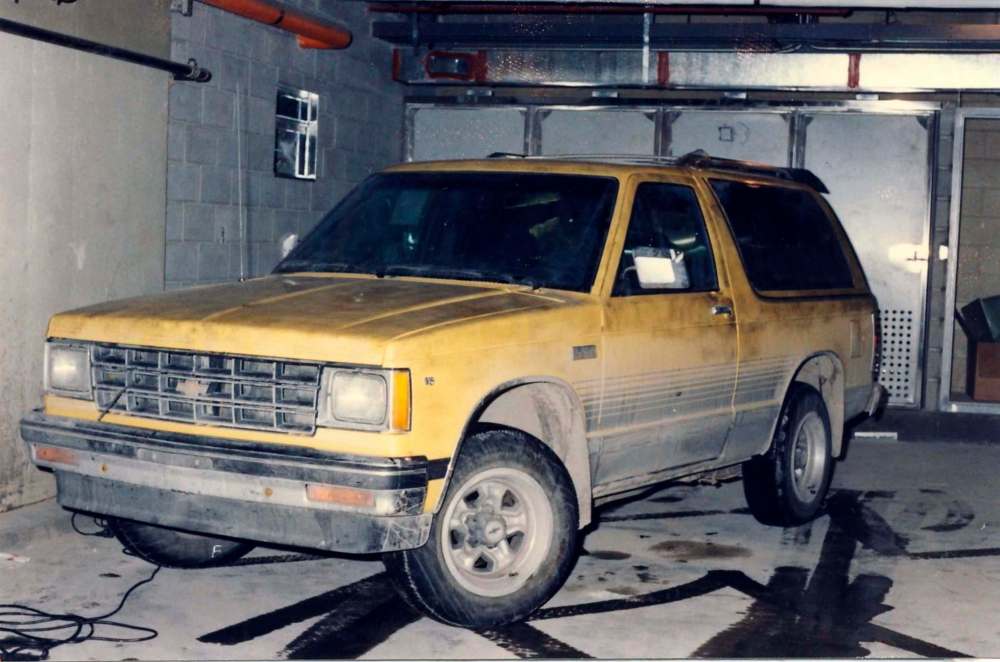

To hear Brian Jack tell it: after putting the kids to bed, he and his wife got into an argument. Christine walked out the front door, jumped behind the wheel of their yellow Chevrolet Blazer and drove off, never to be seen again.

But the Crown prosecutor said that night Christine told her husband she wanted a divorce and he murdered her, later hauling her body into the back of the family SUV and dumping it somewhere.

Newspaper clippings from 1988 offer a timeline of the events that followed.

‘There was just so much evidence that pointed in his direction. I wish he could find it in his heart to help us find her remains, or give us a clue, or tell somebody to tell somebody where she is’

– Kairsten Fatland, Christina Jack’s daughter on her father, Brian Jack

Brian Jack called Winnipeg police the following day to file a missing persons report. His wife’s family and friends suspected the worst, certain she would never have willingly abandoned her children.

Two days before Christmas, police received an anonymous tip from a man identifying himself as “Henry,” saying a vehicle matching the description of the family’s Blazer could be found behind a Salisbury House restaurant at St. Anne’s Road and Fermor Avenue.

Later, when confronted with evidence the anonymous call was made from inside his home, Jack admitted it was him, telling police: “So I called it in; so what?”

He was picked up by police for questioning on Christmas, spending 30 hours in the Winnipeg Remand Centre. Police didn’t have a body, but investigators found blood stains on a freshly laundered couch cushion in the family room. Jack told them he had been skinning a deer in the house.

He was charged with second-degree murder on Dec. 26.

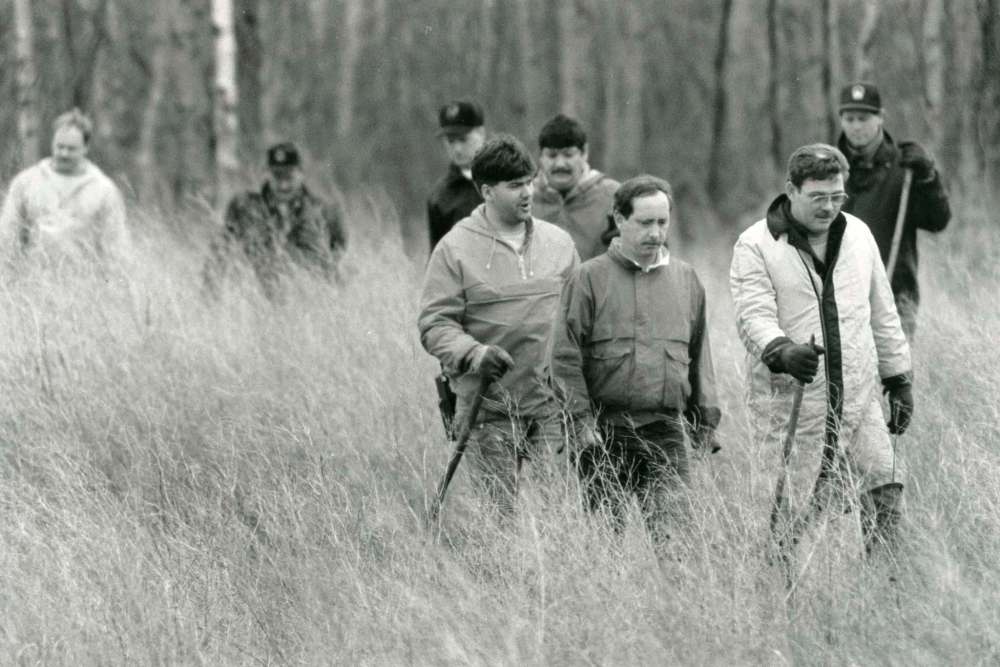

Massive ground searches are launched by city police and RCMP, who combed through areas in St. Anne, Falcon Lake, Steinbach and Winnipeg. At the Brady Road landfill, officers sift their way through hundreds of kilograms of garbage looking for evidence.

False leads, rumours and calls from self-professed psychics flooded police tip lines. Eventually, the searches were called off.

Twenty-one months later, in September 1990, Jack’s second-degree murder trial began.

In his opening statement, Crown prosecutor Jack Montgomery laid out his case, saying that while it was circumstantial, it added up to “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

“It will all come together like a puzzle, a picture puzzle, when the last piece is put in place,” he told the jury.

Weeks later, during closing arguments, Montgomery summed up the case.

“Christine Jack was killed in the family room of her home on Saturday, Dec. 17, 1988…. And there was one eyewitness to this tragic death of the young woman, the husband…. the man who killed her, the accused, Brian Gordon Jack,” he told jurors.

“Christine Jack did not get up, grab her winter coat and purse, and drive out in the Blazer. The dead do not rise and walk.”

But, defence lawyer Richard Wolson spun a different yarn, one in which the police investigation was one-sided rush to judgment that didn’t pursue leads that could have exonerated his client.

The jury disagreed and found Jack guilty of second-degree murder; he was sentenced to life in prison.

But what seemed like the end of a gruesome, tragic crime was just the end of the beginning.

In January 1992, the Manitoba Court of Appeal granted Jack a new trial in which the verdict was not guilty.

The Crown appealed the acquittal and in May 1994 the Supreme Court of Canada ordered a third trial. Jack was found guilty of the lesser charge of manslaughter and sentenced to four years in prison.

That led to another appeal, which made its way — once again — to the Supreme Court. In June 1997, the court ruled a fourth trial would be an abuse of process.

In 2001, Montgomery authored Trials & Errors: The People vs. Brian Gordon Jack, outlining the odyssey, calling it a “sorry tale of one colossal miscarriage of justice.”

‘Sometimes I have less hope and something like that comes and I get hopeful again. Then when (police) called to say no, it wasn’t my mom, you kind of get down. It’s just a roller-coaster of emotion’

– Kairsten Fatland upon learning of the discovery of human remains in the RM of Tache

Fatland has a well-worn copy of the book she’s read many times. She says she returns to its pages to go over forgotten details.

She was thinking about the case again recently, as she often does, near the end of October when human remains were found in the RM of Tache, naturally wondering whether they were those of her mother.

A few weeks later the remains were identified as belonging to Thelma Krull, a Winnipeg grandmother who went missing in 2015, giving her family and friends the closure that Fatland seeks.

“Sometimes I have less hope and something like that comes and I get hopeful again. Then when (police) called to say no, it wasn’t my mom, you kind of get down. It’s just a roller-coaster of emotion,” she says.

Nonetheless, knowing some families get answers years, if not decades, recharges her fading hope.

On Tuesday, Fatland will gather with family in her home in Iowa, where she and her brother, Adam, were raised by their mother’s parents.

“I think it’s hard for everybody. We’ll go to church, spend time together and just kind of talk about her. But we also talk about her throughout the year, too,” Fatland said.

“With my children, I constantly talk about Grandma Christine. We try to keep her alive. My Grandma says she sees signs of my mom in my kids, so that’s pretty special.”

In 2008, Fatland wrote two letters to her father, who is still believed to be living in Manitoba. She asked him to tell her where they could find her mother — even just a bone fragment, something that could be buried.

There was no response.

She continues to pray for an answer.

“It’s hard, but you just can’t help but hold onto that last little bit of hope.”

ryan.thorpe@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @rk_thorpe

Ryan Thorpe likes the pace of daily news, the feeling of a broadsheet in his hands and the stress of never-ending deadlines hanging over his head.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.