Inquest report details Stony Mountain inmate suicides Judge can't make recommendations to Ottawa

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 06/09/2018 (2656 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The staggering challenge of imprisoning people with mental illness was laid bare in a provincial inquest report on the suicide deaths of two Stony Mountain Institution inmates.

Devon Sampson, who died Nov. 23, 2013 at age 34, was suicidal and schizophrenic when he hanged himself in his cell with a shoelace.

Dwayne Mervin Flett, who died on April 15, 2015, had the cognitive ability of a five year old, was suicidal and schizophrenic and taken advantage of by other inmates when he hanged himself in his cell with a bed sheet.

Under the Fatalities Inquiry Act, a mandatory inquest was held to determine the circumstances relating to the deaths of Sampson and Flett, and whether they died “as a result of a violent act, undue means or negligence or in an unexpected or unexplained manner or suddenly of unknown cause; or that a person died as a result of an act or omission of a peace officer in the course of duty.”

A report by provincial court Judge Brian Corrin released Thursday details the experiences of two mentally ill inmates in the federal prison system where the proportion of offenders with mental illness is increasing. In 1997, seven per cent of male offenders entering federal prison were diagnosed as having a mental-health disorder. By 2008, the proportion increased to 13 per cent, a rise of 86 per cent, Corrin said citing federal data. The leading cause of unnatural death in prison is suicide, which occurs at a rate several times higher than in the general population, and psychosis is a risk factor for suicide, the inquest learned.

Sampson was six years old when he immigrated from Guyana. In 1995, at 15, he became involved in the youth criminal-justice system. In 1999, at 19, he was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Over the next six years he was hospitalized several times for months at a time. Psychiatrist reports showed Sampson had a history of not taking his medication and resisting treatment and he’d developed an addiction to crack cocaine.

In 2003 and 2004, he served time in provincial institutions for offences related to theft, weapons and robbery. He entered the federal correctional system in 2005 when he was sentenced to three years for several robberies.

A nurse who worked with Sampson at Stony described him as “always” being at some level of “mentally ill,” Corrin’s report said. Sampson spent a lot of time in administrative segregation, otherwise known as solitary confinement. After assaulting a male nurse on Nov. 10, 2013, he was placed back in segregation. Less than two weeks later, he was found hanging by a shoelace from the upper bunk in his segregation cell. Corrections, nursing staff and paramedics failed to revive him.

Sampson received a “routine” type of monitoring in segregation and not given the attention his special-needs actually required, the inquest report said. For instance, a registered nurse who did some daily checks on Sampson’s well-being while he was in segregation testified that her practice was to announce her presence through a food slot in the door and ask the inmate if he was “OK.” If the answer was “yes,” she’d move on.

After Sampson’s death, a Correctional Service of Canada board of inquiry recommended that all inmates placed in administrative segregation have shoelaces and/or belts taken away. It said all mental-health concerns and diagnoses should be recorded in nationally mandated Institutional Mental Health Initiative Screening intake documents rather than relying on inmate self-reporting. Inmates with mental illness are no longer held in segregation and “alternative placement for such inmates must be found,” the provincial inquest report noted

In June 2011, Flett began his sentence of just under five years for a first conviction that wasn’t revealed in the inquest report. Although in his early 30s, Flett was cognitively similar to a five- to 10-year-old child, the inquest heard. Court records show that his sentencing judge was completely unaware of Flett’s cognitive limitations.

A parole officer said Flett had “childlike mindset” with limited coping skills. He was placed in the prison’s “supportive living range” designed to meet the needs of inmates with general-health or mental-health issues. There he received a mental-health screening assessment that found he had schizophrenia and depressive disorder, as well as a history of suicidal ideation and cognitive impairment.

Between August 2011 and March 2015, Flett was placed on suicide watch 15 times. Flett was easily exploited and often taken advantage of by other inmates. There were suspicions that he was threatening suicide “to remove himself from certain stressors, often threat-related and involving personal debts he owed other inmates on the range — a situation that appears to relate to the socio-economics of inmate subculture, an economy where income and lifestyle enhancements can apparently be generated by predatory and exploitive loan-sharking activities,” the report said.

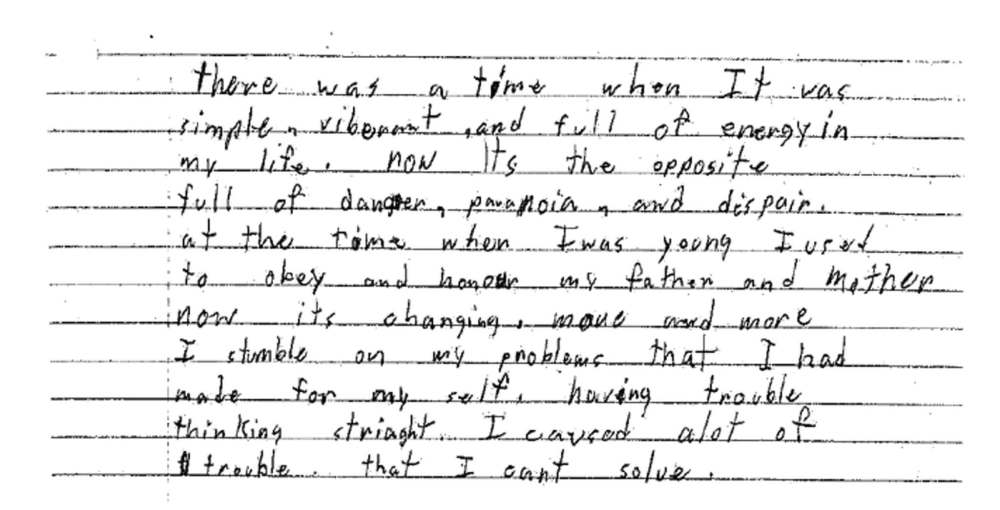

He described experiencing “shadows like stretchy hands” trying to push their way into his brain, causing him distress and thoughts of suicide.” He asked for different medication to “decrease the ‘strain’ on his brain,” the inquest report said. He stopped taking his psychotropic medication — something that was flagged by a mental-health nurse four months before he killed himself.

On April 14, 2015, a few hours before he died, Flett activated his cell call button and told prison staff he was having suicidal thoughts. Security checks were increased from every hour to every half-hour, but he was not placed in a special cell or on a modified suicide watch. At 1:14 a.m., he was found hanging by a bed sheet from a conduit pipe in his cell.

Corrin acknowledged that a provincial inquest is without jurisdiction to make recommendations to the federal government, and that he wouldn’t be sending a copy of his report to the federal Minister of Public Safety. He said it’s up to the Correctional Service of Canada to share it “with anyone of its choosing.”

The Correctional Service of Canada did not respond to a request for comment Thursday.

carol.sanders@freepress.mb.ca

SUICIDE PREVENTION RESOURCES

Manitoba Suicide Prevention & Support Line (confidential, staffed 24/7): 1-877-435-7170 or visit reasontolive.ca.

Suicide Postvention Education Awareness and Knowledge (SPEAK): 204-784-4064 or email speak@klinic.mb.ca.

Brandon & Area Suicide Bereavement Support Group: Contact Kim Moffat, 204-571-4183 or visit spinbrandon.ca.

Parkland Suicide Bereavement Support Group: Contact Shantelle at 204-622-6224 or email discoverlife4you@gmail.com.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, September 7, 2018 1:15 PM CDT: Corrects grammar in photo caption.

1.jpg?h=215)