Outdated construction let fire race through 40-year-old Southdale complex, experts say

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 27/08/2018 (2661 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

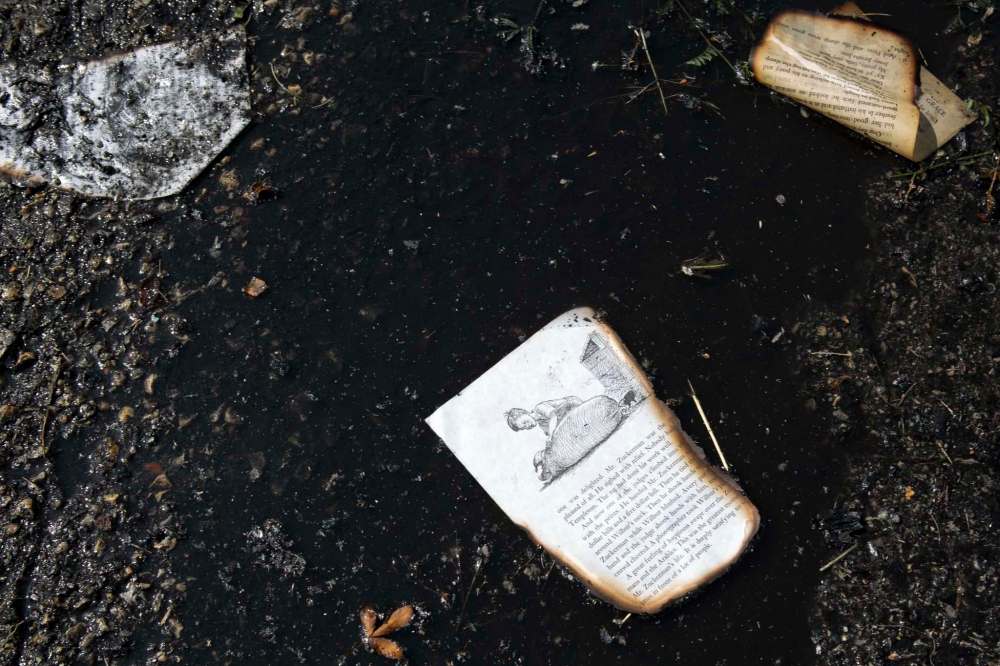

The Southdale apartment block levelled in an early morning Sunday blaze that left 24 families homeless was built to out-of-date construction codes that left it susceptible to flames making quick work of the building.

It’s likely the fire moved so fast through the three-storey complex due to its 1970s, open-attic design built from wooden trusses, experts say. The fire, visible from blocks away, tore through the attic, opening the roof to the sky before the flames jumped onto a neighbouring building.

“Once a fire gets into the attic, those are wooden trusses, so the fire roared through the open attic and the roof started to collapse,” Winnipeg Fire Paramedic Service Assistant Chief Mark Reshaur told the Free Press Sunday.

On Monday, Dustin Pernitsky, communication co-ordinator for the Winnipeg Construction Association, said he wasn’t sure when the open-attic design found in the Southdale apartments was discontinued. The most recent update to the construction code came in 2011. It remains unclear how common the design is in Winnipeg or how many other complexes throughout the city may also have open attics.

Buildings such as the Southdale apartments — located on the 1000 block of Beaverhill Boulevard close to Fermor Avenue — are grandfathered in when new construction codes are implemented. It isn’t feasible to divide an undivided attic after construction is complete, Pernitsky said.

Vladimir Chlistovsky, president of the Canadian Association of Fire Investigators, said as far as he’s aware, there have not been many substantive changes to building codes from the late-1970s, although the division of attics, however, is one that’s been made for good reason.

While Chlistovsky was unable to speak specifically about the fire Sunday, he explained the hazards posed by open-attic designs, in general. “If you look at some of the older semi-detached houses or apartments that were built, the living areas may be separated, but there’s no separation when it comes to the attic space. That means if a fire breaks out in one of the units and spreads up through the ceiling into the attic, then once that fire spreads it goes across the roof and burns the roof off, then spreads damage into the other units,” he said.

“Today’s fire code limits the open attic space to limit the amount of fire spread. Sectioning that attic into smaller spaces helps keep that fire much more contained.”

The apartment at 1085 Beaverhill Blvd. was completely destroyed in the blaze, and the neighbouring building at 1081 was badly damaged. Both were built in 1978.

The cause of the fire remains under investigation. It’s unclear what the final dollar-figure attached to the fire will be, but it’s expected to be in the millions. A representative for Ladco Co. Ltd., the owner of the buildings, has said that both will likely be rebuilt.

The WFPS first received a report of the fire shortly before 6 a.m. and the blaze was finally extinguished at about 7:40 a.m., thanks to the work of 19 fire crews. No one was injured, likely due, in part, to an unnamed tenant who ran through the building knocking on doors to alert other residents. Chlistovsky said investigators sift through the wreckage to determine the origin and cause, a process that could take anywhere from a day to several months, depending on the specific situation. “Sometimes it’s easy, sometimes it’s not. They’ll be using witness statements or video evidence, looking at fire patterns, fire dynamics and knowledge of the electrical system, all to determine that point of origin and potential causes,” he said.

“It’s a process of elimination to get to your origin. Then you have to consider all reasonable causes that may be possible within that origin area.”

— With files from Alexandra Paul

ryan.thorpe@freepress.mb.caTwitter: @rk_thorpe

Ryan Thorpe likes the pace of daily news, the feeling of a broadsheet in his hands and the stress of never-ending deadlines hanging over his head.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.