Inflated statistics, feeble bureaucrats blamed for growing Indigenous poverty gap

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 29/05/2018 (2760 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

OTTAWA — Inflated statistics, flimsy goals and feeble bureaucrats are impeding Ottawa from closing persistent socioeconomic gaps for Indigenous people, according to two audits tabled Tuesday in Parliament.

“We don’t see those gaps closing, we don’t even see that they know how to measure those gaps,” auditor general Michael Ferguson told reporters, chalking it up to “incomprehensible failures” by the federal government.

A study published last October by the Centre for the Study of Living Standards found Manitoba will squander 11 per cent of its workforce growth over next two decades if the gap in Indigenous people’s employment and schooling persists.

Ferguson found Ottawa has been hapless at fixing those problems, especially in First Nations communities.

He found the federal government has been reporting a high-school graduation rate on reserves that is almost double the actual number of students who get a diploma. That’s because Ottawa counts who enters Grade 12 and compares it with how many complete the term, instead of tracking everyone who enters Grade 9 through to the end of Grade 12.

Over five school years ending in 2016, Ottawa said 46 per cent of First Nations teens on-reserve had completed high school; the actual number is 24 per cent.

Auditors noted the Manitoba government does a more accurate, annual count for students off-reserve, but Ottawa opts for the Grade 12 one on-reserve.

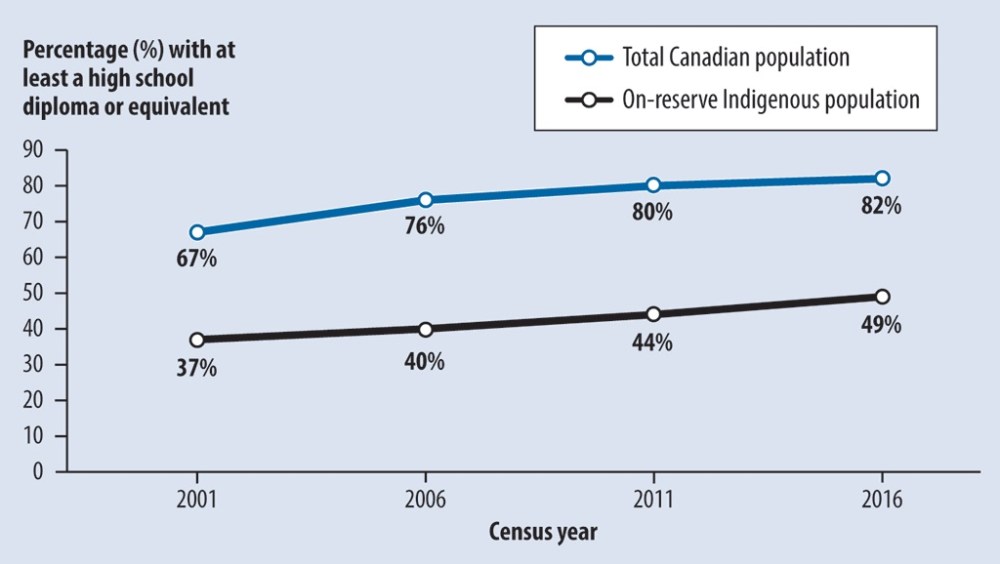

In any case, the gap in high-school graduation between reserves and the rest of Canada has widened since 2001.

Ferguson’s team also found bureaucrats don’t use the datasets available to them from federal departments, band councils and provinces, meaning they have a limited picture of both schooling and employment on reserves.

“It’s not a matter of that they need to collect a lot more data, or they need to do some sophisticated analysis of the data. They just need to look at what the data they already have is telling them — and most of it is pretty obvious.”

The audit also revealed the Assembly of First Nations directed its education committee in July 2017 to pull out of a year-long effort to help public servants craft an assessment tool for students on-reserve, over concerns it was going too fast and not reflecting band-council autonomy.

The AFN said Tuesday that was an accurate characterization of what happened.

Indigenous Services Minister Jane Philpott said her government was still able to shape its education policy with the AFN committee’s help and ultimate approval. “There’s still more work to do on that area. This is a new world where we are co-creating outcome metrics with First Nations, for First Nations,” she said.

Philpott said the Liberals’ move last summer to split the former Indigenous Affairs into two departments means her team can give more attention to such tasks.

She touted a “regional performance-measurement” approach, so students on Manitoba reserves don’t get assessed through tools designed in Ottawa.

Another audit found issues with the two major programs aimed at “securing sustainable and meaningful employment” for First Nations, Métis and Inuit. The audit revealed bureaucrats wrote off short-term gigs under that category.

“They didn’t have a definition of what sustainable employment means. So even if somebody got a part-time job, or a job for five days working on a construction project, they counted that as one of the clients getting a job,” Ferguson said.

Labour Minister Patty Hajdu said a new employment program will also be designed in lockstep with Indigenous people, instead of “paternalistic programming” she blamed on her Conservative predecessors.

She said the new program will assess types of job, pay, contract duration and whether it meets local labour needs.

Ferguson said his reports continue to find a public-servant “culture” that focuses on arbitrary goals over actual outcomes for Canadians, and hiding problems from higher-ups who direct departments.

“I think it’s very much that there’s something in the culture that makes people believe that they can’t bring forward these problems; (that) the system is not going to work.”

dylan.robertson@freepress.mb.ca

History

Updated on Wednesday, May 30, 2018 4:21 PM CDT: Corrects facts related to student counts.