Diagnosis: disaster Government, health officials dismantled Manitoba's hospital system, ignoring warnings from those on the front lines

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 29/10/2021 (1499 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The rumblings came early, shortly after the Progressive Conservatives were sworn into power with a strong majority mandate in May 2016, following 17 years of NDP rule that left the province with a skyrocketing deficit.

Those attuned to the pendulum swings of provincial politics, and those on the front lines of the health-care system, knew cuts were coming. The only question was how deep and severe they would be.

The first changes to the health file were rolled out that fall, mostly around the edges: the possibility of privatized MRIs was floated; a reduction of $650,000 in funding to the Manitoba Metis Federation for medical staff was announced; and a single quick-care clinic was closed.

But behind the scenes — in the backrooms of the Manitoba Legislative Building and in the offices of Winnipeg’s health bureaucrats — big changes were in the works. Those in the know were certain it was only a matter of time before the other shoe dropped.

And when it did, it fell hard.

In February 2017, then-premier Brian Pallister revealed his government was cancelling more than $1 billion in health-care infrastructure projects, the first major spending slash to come to light. It was only the opening salvo, a sign of the reckoning to come.

Over the next three years, Manitoba’s Tory government embarked on the most radical consolidation of health-care services the province had seen since the late-1990s, the last time the party held office.

A Free Press investigation, which included interviews with front-line doctors, nurses and health-care associations, and a review of public reports and leaked internal health authority documents and communications, paints a dire picture of the impacts of the consolidation efforts.

The ambitious plan was pushed through without a risk assessment and with limited consultation with those on the front lines. The results were disastrous, resulting in a reduction in ICU beds in Winnipeg and a nursing staff shortage in the leadup to the COVID-19 pandemic.

With the benefit of hindsight, we now know that at the precise moment Manitoba should have been increasing its ICU bed base, expanding its nursing staff and ramping up its critical-care surge capacity, it was doing the exact opposite.

Over and over again, physicians, nurses and their professional associations raised serious concerns to government officials and health authorities, warning that a pending calamity was on the horizon. It was only a matter of time, they said, before lives were lost.

Even when the architect of Manitoba’s health-care reforms, Dr. David Peachey, said Phase 2 of consolidation should be put on pause — citing staff burnout and unrealistic timelines — the government forged ahead.

The result was a third wave of the novel coronavirus pandemic that saw Manitoba become the first province in Canada forced to ship patients to other jurisdictions due to a health-care system pushed to the brink of collapse.

Not only was the situation predictable — it was predicted, time and time again.

The aim of consolidation was to improve emergency room wait times and find efficiencies in the system to help balance Manitoba’s books after years of deficits. Money was saved — yes — but Manitobans still ended up paying: the bill just came in a different form.

When the pandemic hit, instead of dollars, we paid in human misery.

● ● ●

There have been two major consolidation of Manitoba’s health-care system in recent decades. The first came in 1997-98 with the creation of regional health authorities, which were aimed at centralizing medical services and standardizing the quality of care across hospitals.

Prior to the 1997-98 consolidation, which was implemented during the waning years of the Tory government led by former premier Gary Filmon, health care in Manitoba, particularly in Winnipeg, was deeply siloed, with each hospital largely managing its own affairs.

This resulted in frequent duplication of services, wasted resources and uneven levels of care.

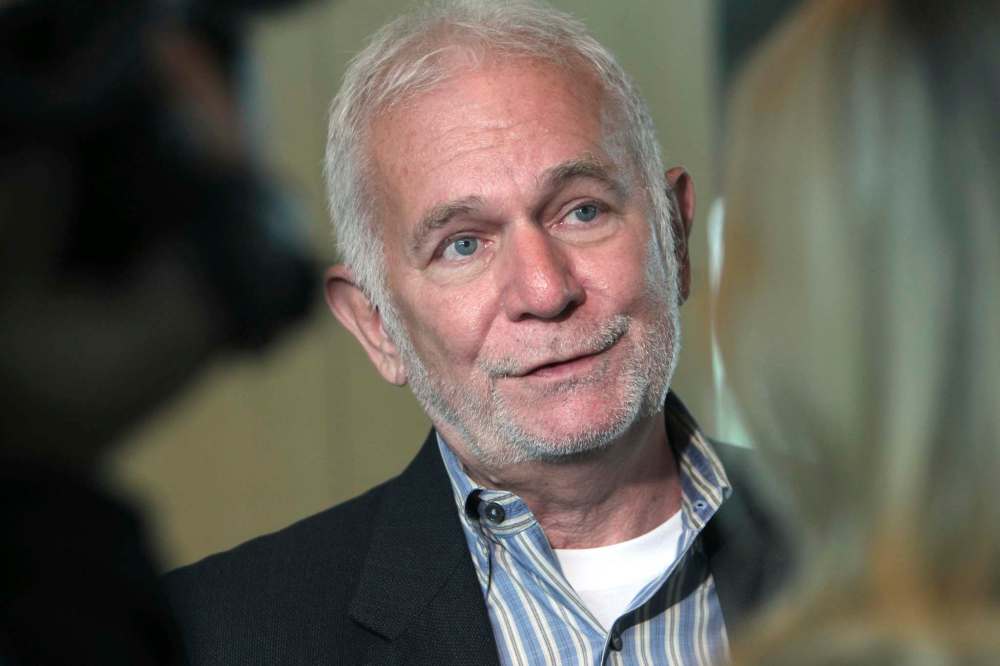

That same year, Dr. Dan Roberts was named regional head of critical-care services in Winnipeg, a position he held until 2001. In that role, he oversaw the consolidation of ICU departments in the provincial capital.

“It was a great leap forward in how we delivered care,” Roberts said in a recent interview with the Free Press, adding the overhaul had the effect of streamlining and standardizing medical programming across hospital sites.

In the years following that consolidation, there were additional reforms around the edges of the system implemented by the NDP — led first by premier Gary Doer and later by his successor Greg Selinger — but nothing like what had been seen under the previous regime.

According to a former Winnipeg Regional Health Authority official who spoke on the condition of anonymity, on multiple occasions the NDP sent back to the drawing board proposals for more sweeping changes as “not fully baked.”

But towards the end of Selinger’s leadership, the NDP hired Peachey — a doctor-turned-consultant based in Nova Scotia — to undertake a systematic accounting of the state of Manitoba’s health-care system and draw up a slate of proposed reforms.

Peachey’s report wasn’t finalized until after the NDP was voted out of office in the spring of 2016. When his proposals were revealed to the public, they were deeply polarizing: some called them “unconscionable” and “doomed to fail,” while others welcomed them as a logical next step.

The Tories were quick to seize on the report as they set about cutting the fat from the provincial budget. Early into its first term in office, the Pallister government revealed to the public that Manitoba’s deficit had soared to more than $1 billion.

Many in the health-care system recognized there was a need for change.

Roberts said Peachey’s recommendations were “reasonably solid,” while a former WRHA official told the Free Press the report contained a mix of good ideas and proposals that “raised eyebrows” due to the perception they had more to do with cutting costs than improving care.

Manitoba Nurses Union President Darlene Jackson was more scathing in her assessment, saying it was clear from the get-go that “when Pallister came to power he had an austerity agenda and health care was on the cutting board.”

Throughout the planning stages of the 2017 consolidation, doctors and nurses — the front-line staff who would presumably be best positioned to know what was and wasn’t working in the health-care system — were largely left in the dark.

Every medical professional the Free Press spoke to for this story said the consultation process at the time was minimal to non-existent — a decision which would have dire ramifications when the plan was rolled out.

“After the change in government, you’ve got the province saying, ‘We’ve got to balance the books come hell or high water.’ Plus you’ve got an external adviser (Peachey) saying, ‘Here’s a rationale to consolidate some services,” one former WRHA official said.

“And so the stars kind of aligned to move forward on consolidation.”

● ● ●

The face of the Tories’ consolidation plan was then-health minister Kelvin Goertzen, the Steinbach MLA who currently serves as Manitoba’s interim premier following Pallister’s resignation in August. He got his start in provincial politics as a party intern during the Filmon years.

One month after Pallister revealed that $1 billion in proposed health-care infrastructure projects would be cancelled, Goertzen announced in March 2017 that the regional health authorities would have their budgets cut for the 2017-18 fiscal year.

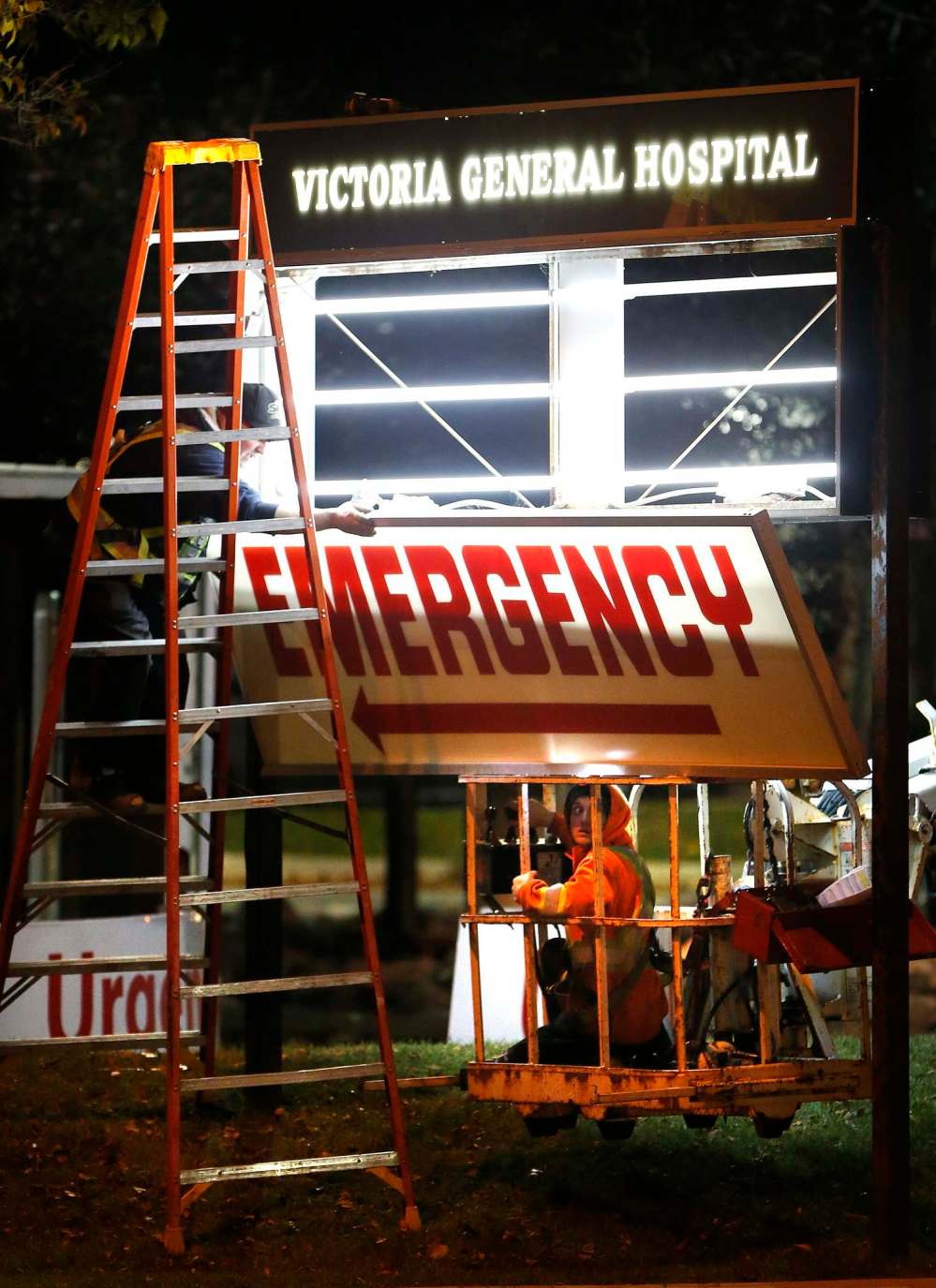

The WRHA was instructed to reduce its budget by five per cent, to the tune of roughly $83 million. The following month, Goertzen announced the emergency rooms at Seven Oaks, Concordia and Victoria hospitals would be shuttered.

By June, nearly 200 jobs were cut to comply with directives from the province to reduce management positions in the regional health authorities by 15 per cent. The closure of four more quick-care clinics in Winnipeg came in July, followed by the layoff of 500 nurses in August.

In November, funding for personal-care homes in the province was slashed by $1 million.

The consolidation plan had wide-ranging impacts throughout the health-care system, but Winnipeg’s ICUs took the brunt of the blows. As part of the overhaul, the number of ICU beds in the city was reduced from 76 to 63.

In order to justify the cutback of Winnipeg’s critical-care bed base, the province and health authorities put forward a theory, proposed by Peachey, that the reduction in ICU capacity would be workable if patient flow was improved.

According to WRHA statistics obtained by the Free Press, the average number of transferable patients in Winnipeg’s ICUs was 8.4 in 2016-17. That means there were usually eight people who could be transferred out of an ICU bed if there was somewhere to send them.

The province and health authorities said they would develop a plan to improve patient flow out of the ICU — so people who didn’t need critical-care beds weren’t occupying them.

In other words, the bottlenecking in Winnipeg hospitals would be alleviated, resulting in more ICU capacity — not less — despite the reduction in the overall bed base. In reality, that never happened; in fact, the problem got worse.

By 2018-19, WRHA statistics showed the average number of transferable patients in the city’s ICUs had jumped from 8.4 to 9.4.

Ideally, health administration sought to always have nine open ICU beds across all Winnipeg hospitals to ensure appropriate room for incoming patients. Again, consolidation made it worse.

From 2016-17 to 2018-19, according to internal WRHA statistics obtained by the Free Press, the number of days with fewer than nine ICU beds available in city hospitals spiked by 57 per cent.

Nursing vacancies in Winnipeg also got worse. In June 2017, the vacancy rate in the city was 15 per cent; by September 2019 — five months before the onset of the pandemic — it had risen to 19.4 per cent.

The staffing shortage also held true for critical-care units: from February-November 2019, the number of ICU nursing positions funded in Winnipeg dropped from 349 to 318.

The province and health authorities had assumed ER and ICU nurses who worked in hospitals that were losing their emergency rooms and critical-care wards would transfer to another hospital to keep working the same job.

But many chose to stay put, remaining at their community hospital and simply transferring into a new job in a different department. This put a further strain on the staffing complement in Winnipeg’s remaining ERs and ICUs.

“It takes real talent to turn a bed reduction into a nursing shortage.”–Dr. Dan Roberts

Jackson said it’s something the province and health authority administration would have learned had they conducted a risk assessment or done proper consultation with front-line staff prior to rolling out a major overhaul.

Due to the nursing-staff shortage resulting from consolidation, not even the proposed reduction in the ICU bed base to 63 was implemented by December 2019. There simply weren’t enough nurses to staff all of the beds.

“It takes real talent to turn a bed reduction into a nursing shortage,” said Roberts.

The Free Press requested a statement from Goertzen — responding to a series of written questions — but instead received comment from a government spokesman.

The statement began by attacking the record of the previous NDP government, arguing the issues with critical-care capacity in Winnipeg hospitals “were not addressed” during the party’s “nearly two decades in office.”

“The NDP-commissioned Peachey Report identified that there were too many critical care ‘beds on paper’ that lacked in-hospital support of nurses, physicians, or multidisciplinary teams including respiratory services,” the statement reads.

“As a government we are committed to acting on the advice of health-care experts and system leaders to deliver better health care — that focuses on reduced wait times, improves access and more services in communities closer to home — for all Manitobans.”

But the claim that government was acting on the best available advice from health-care experts — rather than pursuing an ideologically motivated cost-cutting agenda — is contradicted by Roberts, who said the theory used to justify the reduction in ICU beds was “sheer nonsense.”

As the regional head of critical care services in the 1990s, Roberts had built a database that tracked every admission to Winnipeg’s ICU wards. By 2017, there was a full 20 years of data that gave a “solid, informed picture” of how many beds were needed.

Roberts said the Peachey Report relied on “questionable” data pulled from other provinces. Even worse, Roberts was ignored when he tried to take his dataset to the provincial government and health officials.

Peachey declined comment for this story.

“We had an enormous amount of data. Nobody wanted to look at it. We put the reports together and said, ‘This is (the ICU bed base) we need.’ Nobody listened,” Roberts said.

“We did an analysis and we calculated that we needed at least six to 10 extra beds. We were looking at 20 years of data that showed the surges. It showed how many transferable patients you had at any time of day. We had all the data you could need.”

“We had an enormous amount of data. Nobody wanted to look at it. We put the reports together and said, ‘This is (the ICU bed base) we need.’ Nobody listened.”–Dr. Dan Roberts

According to Roberts, the concerns over patient bottlenecking in Winnipeg’s ICUs was a red herring, largely due to transfer protocols he’d developed working as a critical-care physician. The real issue was and always had been too few ICU beds.

Why, then, did the government and upper echelons of the health authorities ignore his pleas and rely instead on data pulled from other jurisdictions?

“Because they had an agenda, and the agenda was to cut costs,” he said.

“The decisions on what needed to be changed were being made on a political basis.”

● ● ●

By the summer of 2019, the situation in Winnipeg hospitals had reached a breaking point. In increasing numbers, health-care professionals were taking their concerns directly to the provincial government and the heads of the WRHA and Shared Health.

A review of leaked documents and correspondence obtained by the Free Press shows alarm bells were repeatedly rung by doctors and nurses. Yet each time concerns were raised about the lack of critical-care resources in Winnipeg — beds and ICU-trained nurses — they were ignored.

In April 2019, in an effort to address low morale, former WRHA president and CEO Real Cloutier sent a letter to 28,000 staff telling them to hang on, describing their current situation as the “valley of despair” — a concept pulled from change-management literature.

Peachey himself, a month later, wrote in a report addressed to then-health minister Cameron Friesen that ongoing consolidation efforts should be “paused immediately.”

“Workload and staffing instability in the nursing workforce are significant and not sustainable…. The current challenges can be tracked back to the absence of ongoing needs assessment and, particularly, to the absence of a formal regional risk assessment,” Peachey wrote.

“Confidence has been lost…. (It is) entirely predictable that the quality of nursing care to patients is and will be compromised.”

”Confidence has been lost…. (It is) entirely predictable that the quality of nursing care to patients is and will be compromised.”–Dr. David Peachey

In July 2019, WRHA critical-care physicians sent a report to health authorities unequivocally stating that: “Critical care bed numbers must be increased.”

“We have already witnessed a negative impact from earlier changes and are concerned that these proposed changes would further impair our program’s ability to provide safe and effective care that criticaly ill patients require,” the document reads.

By October 2019, Roberts wrote directly to Friesen, laying out his credentials as a critical-care physician and former regional head of Winnipeg’s ICU units. He said the city’s hospitals lacked even the critical-care capacity to respond to a worse-than-average flu season.

“I am writing to express my concerns regarding the state of intensive care resources in Winnipeg, with the hope that appropriate measures can be taken to avert an impending calamity,” he wrote in a letter dated Oct. 23, 2019.

His letter ended on an ominous note: “I strongly suspect that by January or February we will all profoundly regret not having dealt with this problem. Inquests often have that effect.”

Friesen did not respond.

By the following month, critical-care physicians across the WRHA and Shared Health chose to write a collective letter to the heads of both authorities, arguing that “inadequacies of both the ICU bed base and ICU nurse (staffing)… have precipitated a wider crisis.”

“As intensive-care physicians, we are gravely concerned that current ICU bed and nursing crises will contribute to significant and avoidable patient morbidity and mortality. With inadequate ICU beds, a severe flu season will be catastrophic,” the Nov. 4, 2019 letter reads.

Again, little was done to change course or ramp up ICU capacity in Winnipeg’s hospitals.

On Jan. 8, 2020 — roughly two months before Manitoba declared a state of emergency due to the arrival of COVID-19 — Doctors Manitoba wrote to the heads of the WRHA and Shared Health to again raise concerns and demand a plan of action.

“The situation is now extremely concerning. Critical care specialists are describing this situation to us as a ‘crisis’ and ‘unprecedented’…. Doctors are now in an untenable position of determining which critically ill patient receives an intensive care bed and which does not,” the letter reads.

Weeks earlier, the first warnings of a strange new illness in Wuhan, China began to trickle out to the world through news reports.

Sixty-four days later, Manitoba recorded its first presumptive case of the novel coronavirus.

And six months after that, COVID-19 ravaged the province’s long-term care facilities, with bodies left for dead. And soon after that Manitoba’s ICU patients were being airlifted across the country because the overwhelmed critical-care system buckled.

● ● ●

By the time Roberts realized no one in provincial government or among the health-care officials overseeing consolidation would listen to his pleas that reducing Winnipeg’s ICU bed base was a bad idea, he resigned himself to sit and wait for a crisis.

“I figured, ‘I’ve said my piece, nobody is listening, we’ll wait till disaster happens. That’s what we’ll have to do. And then they managed to scrape through the winter (2019) flu season, but there were still impacts during that flu season,” Roberts said.

“There were difficulties getting patients admitted to the ICU. There were people who stayed in emergency on ventilators. It was obvious that we didn’t have enough beds.”

It was a harbinger of things to come.

A Manitoba government spokesperson said no one “could have predicted the unprecedented challenges posed by COVID-19 and its impact to our health-care system and the people who work in it,” adding that every province was “significantly challenged” during the pandemic.

“(During) the pandemic we maximized existing space in our major ICUs, we added usable beds with adequate staffing to reach our pre-pandemic baseline,” the spokesperson said in a written statement.

“Then, through a variety of means and every measure at our disposal, we more than doubled that capacity during the pandemic to protect Manitoba’s most vulnerable.”

But each time during the pandemic that public-health officials announced the expansion of the province’s critical-care services, Jackson couldn’t help but shake her head.

“They kept making these announcements, ‘We’re going to create 60 more positions in critical care.’ Well as far as I’m concerned, all you’re doing is creating 60 new vacancies, because we don’t have enough nurses to fill the vacancies we have now,” she said.

The strategy seemed to be “robbing Peter to pay Paul,” she added, by transferring nurses from other programs into the ICU, only to create new staffing holes in other departments.

“It just seemed to be a snowball that was getting bigger and bigger and rolling downhill. The Manitoba Nurses Union was loud and clear that you can’t just take a bandage and slap it on a gaping wound and hope nobody notices,” she said.

“They kept making these announcements, ‘We’re going to create 60 more positions in critical care.’ Well as far as I’m concerned, all you’re doing is creating 60 new vacancies, because we don’t have enough nurses to fill the vacancies we have now.”–Darlene Jackson

Doctors Manitoba said in a written statement that it remains concerned about how hospitals were “pushed beyond their limits” during the height of the pandemic, resulting in the cancellation of nearly 130,000 surgeries and diagnostic procedures.

A spokesperson for the non-profit noted that critical-care physicians had been “raising serious concerns about the state of our ICUs for months” before COVID-19 arrived in Manitoba, and that during the pandemic their views were “not sought or welcome.”

But the spokesperson also said the agency has seen a “change in tone and approach” in recent months, with the provincial government increasingly reaching out and seeking physician input on a more consistent basis.

Nevertheless, the Doctors Manitoba spokesperson said there must be an inquiry into the Tories’ consolidation efforts from 2017 to 2020 in light of the pandemic.

“We trust the government and health system will conduct an open and transparent investigation into what happened, and how decisions before the pandemic to consolidate Winnipeg’s hospitals and reduce ICU beds may have contributed to this situation,” the statement reads.

“Doctors Manitoba will support and participate in such an inquiry.”

A former WRHA source who spoke on the condition of anonymity said the reduction in critical-care beds and ensuing staffing pinch among ICU nurses undoubtedly impacted Manitoba’s ability to effectively respond to the pandemic.

“It’s like building a dike and then expecting the water to almost hit the top of that dike year after year. Every couple of years, a little bit will spill over the top. But then, every 10 or 20 years when there’s a flood, you’re under water.”

“The problem turned to people…. When the pandemic hits, the system was extremely vulnerable to even a small surge in the number of patients in critical care. The system was redesigned to run so close to the edge. There was no cushion, no ability to flex,” the source said.

“It’s like building a dike and then expecting the water to almost hit the top of that dike year after year. Every couple of years, a little bit will spill over the top.

“But then, every 10 or 20 years when there’s a flood, you’re under water.”

ryan.thorpe@freepress.mb.ca Twitter: @rk_thorpe

Ryan Thorpe likes the pace of daily news, the feeling of a broadsheet in his hands and the stress of never-ending deadlines hanging over his head.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

.jpg?h=215)