The straight poop Manitoba Clinic team's fecal transplant ends patient's year of antibiotic-resistant misery; unique science offers effective, affordable and, yes... icky-sounding infection treatment option

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 24/05/2019 (2396 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

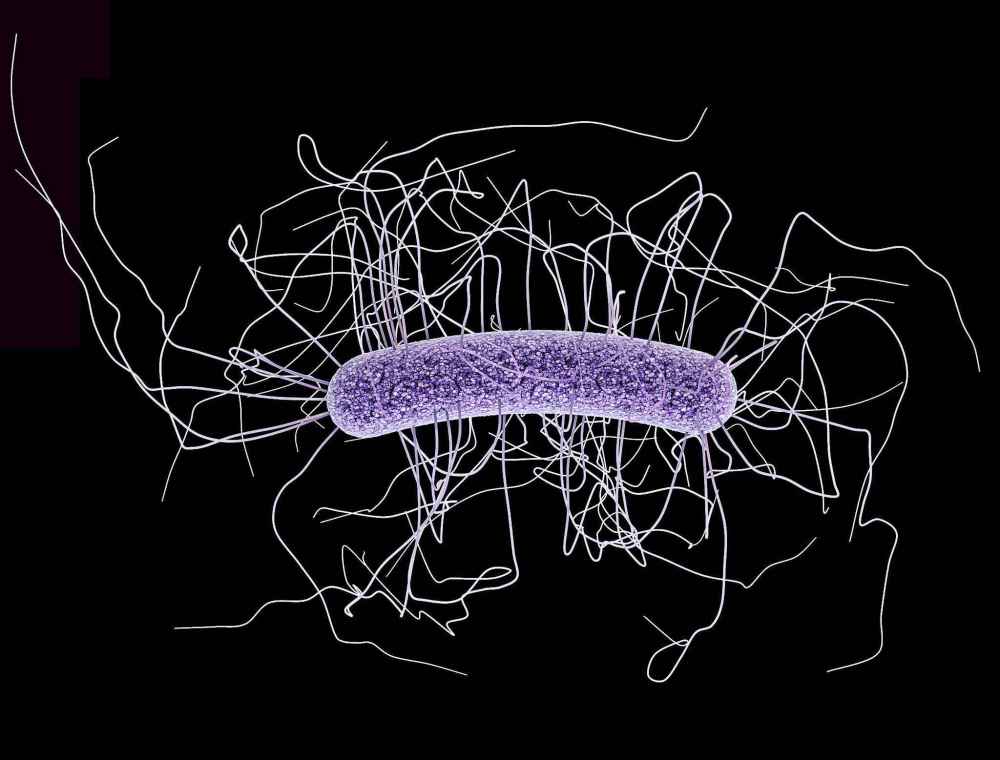

For over a year, the patient had suffered. The symptoms of a stubborn C. difficile infection can derail a whole life: there’s the chronic diarrhea that strikes multiple times a day. The bouts of nausea and searing abdominal pain.

This patient’s infection was more stubborn than most. Antibiotics fell short; at least two rounds of vancomycin, one of the drugs of last resort, couldn’t knock the bacteria out. Each time, the C. difficile came roaring back, along with the symptoms.

At the Manitoba Clinic, Dr. Christopher Schneider finally had a new option to offer. For years, the gastroenterologist had been campaigning to bring a curious but highly effective treatment for chronic C. difficile infections to Manitoba. At last, in the waning days of winter, his team had the approvals they needed to move forward.

On April 3, using a cheap blender, a willing donor and some medical expertise, Schneider and his team performed the first official fecal transplant in Manitoba.

Yes, it’s exactly what it sounds like, and it works: within hours of receiving the poop transfusion, the patient’s diarrhea vanished. Six weeks later, it has not returned. The long-suffering patient was thrilled; in a comment on a doctor-rating website, the individual praised Schneider for bringing hope to people who suffer from C. difficile.

For the doctor, the transplant’s success was almost as big a relief as it doubtless was for the patient.

“I was just so happy that after four years, we finally got it done,” he said during a phone chat earlier this week. “I was really proud of myself and the team that we persevered and got it done… I was a little bit nervous about how everything would go. But we did it for the patient’s sake, and the patient did well.”

Humans have known about the healing potential of poop for thousands of years. In ancient China, a medical textbook dating back to the 10th century BC advised using “golden juice,” a sort of fecal stew, to treat some abdominal distress. Ancient patients would have had to drink it, which seems… unappealing.

Despite this long history, contemporary medicine has been slow to study and embrace fecal transplants. The first randomized study of its efficacy in treating C. difficile was published in 2013. The results were so promising that researchers stopped the trial early. It was beating vancomycin by significant margins.

Why does it work? The mechanism is both simple and incredibly complex. Our bodies, Schneider explained, contain 10 trillion bacteria, outnumbering our own cells nearly by a factor of nearly 10 to one. We are almost, in a way, a home for bacteria above all else, and those microbes work with us in ways we have yet to fully understand.

For instance, in a healthy gut, bacteria flourish in a sort of balanced ecosystem, and the enzymes they create are critical to our digestion. But when a person takes antibiotics to treat another condition, the drugs kill off swaths of those helper bacteria, which can sometimes give C. difficile a chance to run rampant.

From there, doctors and patients often find themselves locked in an ongoing battle. Up to 40 per cent of patients treated with antibiotics will see their infections return or relapse at least once. Each time it does, the likelihood of defeating it with antibiotics shrinks, until they reach the point where there’s little hope left.

But fecal transplant approaches the problem from a different angle. If you can coat a patient’s gut with poop from a donor, someone who still has a healthy balance of gut bacteria, you can restore that balanced ecosystem that was once disrupted. Those bacteria can then do the work of keeping C. difficile in check.

It sounds strange, but it can be incredibly effective. According to a growing body of research, a fecal transplant can cure a C. difficile infection in up to 93 per cent of patients. Once cured, most will not experience a relapse.

‘This is actually one of the most satisfying things in gastroenterology. To take someone with chronic diarrhea, do this transplant and they’re 100 per cent better right away, and they’re so happy. We deal with so much bad news, (telling patients they have) cancer, or colitis… this is a really good-news situation’

And it can be remarkably affordable. C. difficile infection is costly; a 2012 study pegged its impact at $281 million each year to Canadian society in medical costs and lost productivity. Repeated courses of vancomycin can cost thousands of dollars.

By contrast, Schneider says, the cost of the fecal transplant with the first patient was about $275.

“There’s no money in poop,” he says, with an enthusiasm not normally associated with this topic.

The problem, he thinks, is that leaves fecal transplant without many high-powered champions. It holds little interest for private companies, a matter of basic economics. The curative material, in this case, is one where uh… there is no shortage of supply. You could accurately say that vast quantities of it are being flushed down the toilet.

Schneider believed in the treatment. He grew up in Manitoba, but received his gastroenterology training in Quebec, where a particularly stubborn strain of C. difficile had staked a claim. There, he helped prepare many patients for transplant and saw how effective the procedure could be.

When he returned to Manitoba in 2016, he set about trying to launch a fecal transplant program here. He knew there was a need; doctors were sometimes sending patients with tricky C. difficile infections for fecal transplants in Alberta or Ontario, a costly endeavour that could be onerous for a patient.

At first, getting a program up and running here was a frustrating experience bound up in red tape and wrangling over funding, he said. Finally, in late 2017, Schneider decided he’d get a new transplant team up and running himself.

So he partnered with University of Manitoba microbiologist Dr. Ayush Kumar, as well as other researchers. Together, they wrote a protocol to lay out eligibility criteria and procedural steps. In October 2018, the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Manitoba approved it; two months later, the Manitoba Clinic’s board members gave their green light.

It is not a particularly difficult procedure. The transfusion itself, Schneider explains, is not much different than a standard colonoscopy, which is something gastroenterologists do hundreds or thousands of times a year. The biggest challenge is preparing the donor poop to be transfused to a new colon.

To do that, someone on the team went out and bought the cheapest blender they could find at Walmart, Schneider said. With the donor contribution in hand — it has to be, ahem… made fresh — the transplant team added a little distilled water, and mixed it up on the blender’s “smoothie” setting.

The result was a sort of poop slurry that can be infused via medical tubing during the colonoscopy. The procedure takes about 45 minutes, though preparing the patient and the poop takes up much of the day. It’s time-consuming, Schneider said, but the results are worth it.

“This is actually one of the most satisfying things in gastroenterology,” he said. “To take someone with chronic diarrhea, do this transplant and they’re 100 per cent better right away, and they’re so happy. We deal with so much bad news, (telling patients they have) cancer, or colitis… this is a really good-news situation.”

The recipient can choose the donor, who simply has to be screened for infections, such as HIV or gonorrhea.

‘We know more about the surface of the moon than we do our gut microbiota. It’s extremely complex, and it’s something that needs more research, and why not here in Manitoba?’

The new fecal transplant team will be Schneider’s lasting legacy to Manitoba. In September, the specialist is moving to Australia; he is training another Manitoba Clinic gastroenterologist, Ibrahim Abdelgadir, to perform the treatment. They plan to do more of them over the summer.

After that, the program has even greater potential. Fecal transplants are also being studied as a treatment for other conditions. In one study, 24 per cent of patients with ulcerative colitis went into remission after fecal transplant, compared to just five per cent with a placebo, and without any worse effects.

“We know more about the surface of the moon than we do our gut microbiota,” Schneider said. “It’s extremely complex, and it’s something that needs more research, and why not here in Manitoba?”

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.