Names of children who died in residential schools released in sombre ceremony

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 30/09/2019 (2265 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

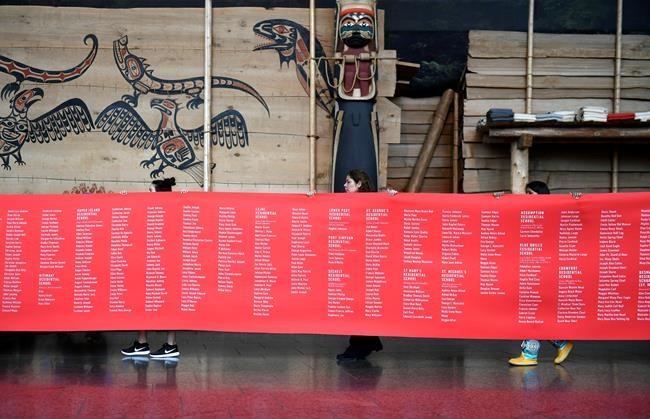

Rose Mary Wolfe in Lestock, Saskatchewan. Bella Johnson in Whitefish Lake, Alberta. Jacob Grey in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. James Paul in Shubenacadie, Nova Scotia.

The list goes on and on — children who died in Canada’s residential school system. Child victims being named for the first time.

On Monday, the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation revealed the names of 2,800 children who died in residential schools during a sombre ceremony in Gatineau, Que.

A 50-metre-long, blood-red cloth bearing the names of each child and the schools they attended was unfurled and carried through a crowd of Indigenous elders and chiefs, residential-school survivors and others.

Many openly wept. Mournful songs performed by Indigenous artists pierced the quiet sadness that hung over the room.

The list has been created to break the silence over the fates of at least some of the thousands who disappeared during the decades the schools operated.

“Today is a special day not only for myself but for thousands of others, like me, across the country to finally bring recognition and honour to our school chums, to our cousins, our nephews to our nieces that were forgotten,” said elder Dr. Barney Williams, a residential-school survivor and member of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation survivors committee.

“I know that the angels in heaven — the names that are on that list — are certainly smiling down on you and me. Smiling down to know that finally, after all this time, they are not forgotten.”

The cloth is the product of years of research conducted on what happened to the many children who were taken into residential schools and never came out. Archivists pored over records from governments and churches, which together operated as many as 80 schools across the country over 120 years. It’s the start of meeting one of the 94 calls to action in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report issued in 2015, which called for resources to develop and maintain a register of deaths in residential schools.

“Today is a special day not only for myself but for thousands of others, like me, across the country to finally bring recognition and honour to our school chums, to our cousins, our nephews to our nieces that were forgotten.”–Dr. Barney Williams

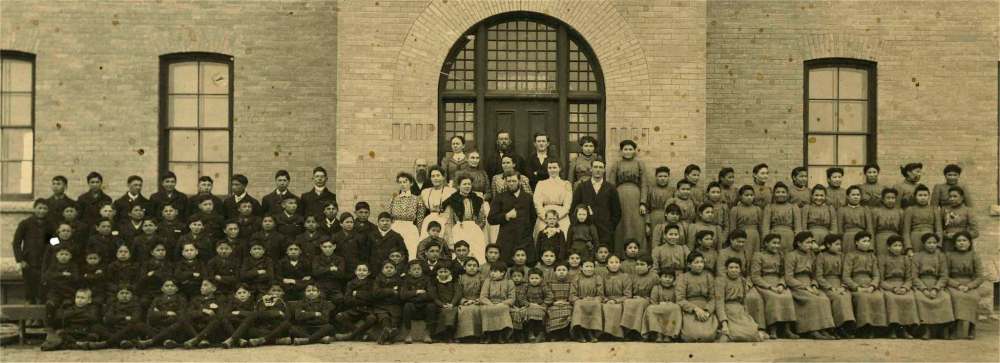

A total of 150,000 Indigenous children are thought to have spent at least some time in a residential school.

“It is essential these names be known,” said Ry Moran, director of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, which compiled the list.

The 2,800 are those whose deaths and names researchers have been able to confirm. Moran says another 1,600 also died, but remain unnamed.

There are also many hundreds who simply vanished, undocumented in any records so far uncovered.

Some schools have an extensive list of students who died; some list none. Moran wonders at such large discrepancies.

“Even our recent research efforts have uncovered another 400 students,” Moran said. “We know there’s many more students to be found.”

“My greatest fear right now, and I think a reality for this country is that there may very well be another day like this in 80 years, remembering the children that are dying today.”–Ry Moran

The age range is wide.

“Infants, three-year-olds, four-year-olds all the way up through their teenage years. We’ve got some students on this list that are named as ‘babies.’ “

A number of national Indigenous officials spoke at the ceremony Monday, which felt much like a funeral for the many young victims of abuse and neglect in residential schools.

National Chief Perry Bellegarde of the Assembly of First Nations mourned for the “little ones,” many of whom were buried unceremoniously in unmarked graves.

He called the deaths of the children in the schools a “genocide” — echoing the findings of the final report of the national inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, which was released earlier this year.

“The residential-school system was a genocide of Indigenous peoples, First Nations peoples, forcibly removing from their homes and inflicting pain,” Bellegarde said during the ceremony.

We’ve got to do better and we can do better and I hope that all Canadians feel that, if we get this right, we’ll be a better, stronger country.”–Ry Moran

“We still feel the intergenerational trauma of that genocide. We see it every day in our communities. But now we say there’s hope, because it’s not just (the term) ‘survivors’ we want to use. The people are … thrivers, starting to thrive, becom(ing) proud of who we are as Indigenous Peoples.”

But not everyone was feeling so upbeat about the current state of affairs for Indigenous children in Canada.

After all, many are still dying of suicide and from the effects of other systemic mistreatment, Moran said.

“My greatest fear right now, and I think a reality for this country is that there may very well be another day like this in 80 years, remembering the children that are dying today,” he said.

Moran noted concerns raised recently by well-known Indigenous advocate Cindy Blackstock, who called for more political attention to a ruling earlier this month from the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal. The ruling found the federal government had been “wilful and reckless” in discriminating against First Nations children living on reserves by knowingly underfunding child-welfare services.

“We live in a country that is still in the midst of a human-rights crisis, profound human-rights violations. We’ve got to do better and we can do better and I hope that all Canadians feel that, if we get this right, we’ll be a better, stronger country,” Moran said.

Although the names of the victims unveiled Monday are public, the details researchers have been able to uncover about them will be restricted to families.

The work won’t stop, Moran added. The team continues to seek the names of the 1,600 others confirmed dead and to find some kind of resolution for the children who disappeared.

Researchers plan to return to First Nations communities to refine the list, fill gaps, and add as much as they can. Many, many graves need to be located.

They will also try to collect as many and as much of the stories behind the names as they can.

“That is the next phase — making sure that when we remember these children, we bring life to them and help understand what really went on. That’s got to be led by the communities and the families. We’re there to help.”

The work has been difficult and draining — “really, really harsh,” Moran added.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Sept. 30, 2019.

215 Manitoba children named

OTTAWA — The names of 215 children who died at Manitoba residential schools were recorded into memory Monday, documenting atrocities dating to as recent as 1974.

“Identifying and putting names out there, I hope, makes it more real to people that these events really did take place,” said Carl Stone, an elder in Winnipeg who advises University of Manitoba students through the Indigenous Student Centre.

On Monday, just outside Ottawa, Indigenous leaders observed as the Winnipeg-based National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation officially released a list of 2,800 names of children who died while attending residential schools in Canada.

The list, published online and organized by school, shows 216 names of deceased children, attributed to 14 schools across Manitoba, with large numbers in places such as Brandon and Sandy Bay, and one death recorded in Churchill.

The deaths date from 1894 to 1974, though more than a dozen are either marked as unknown or within a wide range.

Ry Moran, director of the NCTR, said in addition to the 2,800 recorded names, 1,600 more children died. Their identities are still being gathered, including through information from the public.

“These children call upon us to take action, to stop the harm inflected on children through present-day systems that are broken, racist and based on ongoing notions of cultural superiority," Moran said at the ceremony at the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Que.

“Canada will never be the same, now that these names are known."

Stone, speaking from Winnipeg, said there are still “deniers” who reject the historical consensus that sexual abuse and cultural disorientation were rampant at residential schools.

He said Canadians needs a nuanced understanding, as some people who went to residential school recall horrors of abuse, while others attending the same schools say they had a positive experience.

To him, Monday’s event puts further proof to the findings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, that the schools wrought chaos on Indigenous communities and killed many children.

“To me it makes it real,” said Stone, who led a march last week organized by nursing students, across the campus from their faculty centre to the NCTR.

Hundreds in Winnipeg donned orange shirts Monday, as part of an annual commemoration of the victims of residential schools. It’s a reference to a residential school student who wore an orange shirt from her mother which school administrators disposed of.

“The message is that every child counts,” Stone said.

Barney Williams, an elder who works with NCTR, told the audience Monday the list will help families heal.

"Finally, we have come to a time and a place where it’s not just about survivors now — us, me — but to remember those who didn’t make it home," Williams said.

-Dylan Robertson

dylan.robertson@freepress.mb.ca

Brandon trailer park on site of unmarked residential school burial ground adds further indignity

Posted:

It is a horror story. Or a tragedy. But, all the while, true.

The Free Press acknowledges the financial support it receives from members of the city’s faith community, which makes our coverage of religion possible.