Simple possession of reason averts drug-induced legal absurdity

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 21/06/2018 (2729 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

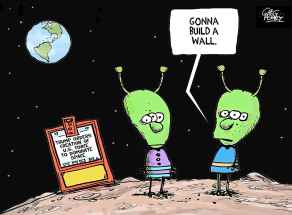

It’s a perverse, almost unbelievable scenario.

One day after the federal government passed the Cannabis Act, which will legalize the possession of small quantities of pot, the federal prosecution service confirmed that it will continue to prosecute Canadians under the old laws right up until the new law is enacted Oct. 17.

Given that it takes months, if not years, to fully process a criminal charge, it raises the distinct possibility that some Canadians will still be earning criminal records beyond Oct. 17 for a crime that police have long since stopped enforcing.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government has known for a long time that this was going to be a problem. Provinces, law enforcement agencies, lawyers and cannabis activists have been warning Ottawa that something needed to be done to provide a just and fair solution for what could be a very unjust and unfair scenario.

To date, Trudeau has stubbornly clung to the idea that as long as the old law is active, there is nothing his government can do to interrupt the prosecution of Canadians for simple possession. Nor, as he made clear this week at a news conference, will he discuss pardons for Canadians who have criminal records for simple possession.

“Until the actual coming-into-force date happens and the law is changed, there’s no point looking at pardons while the old law is on the books,” he said. “We’ve said we will look at next steps once the new (law comes into force). But between now and then, the current regime stays.”

These comments stand in stark contrast to statements the prime minister made during and following the 2015 federal election. Trudeau has consistently suggested that the old Criminal Code provisions on possession were outdated and flawed; numerous times he has promised Canadians he would “fix a broken law.”

Why is he being obstinate about an issue that strikes deep at the spirit of the new law his government has spent so much political capital bringing to fruition? Two possible explanations come to mind.

First, that after the Cannabis Act is proclaimed and enacted in October, Trudeau will, in fact, issue an order quashing all outstanding charges being handled by federal prosecutors. He may go even further, announcing a process by which those convicted of simple possession may seek pardons.

Ottawa may feel that quashing charges and outlining opportunities for pardons before the new law is in place might just encourage cannabis enthusiasts to grab their tiny baggie of pot and rush out onto the street in front of their homes and puff away with impunity, knowing that even if they’re charged, there will be no repercussions. It’s a pretty remote scenario, but there seems to be an abundance of caution in Trudeau’s current posture.

The second explanation is, not surprisingly, pure politics.

It’s pretty clear now that although a solid majority of Canadians support the legalization of cannabis, there is no consensus among provinces, municipalities and law enforcement agencies about the best way to manage the retail sale of what was previously an extremely controlled substance.

Pushing back all discussion about dropped charges or pardons may serve as a bit of tonic for those who are most worried about legalized pot. At the very least, it’s one less thing to worry about now.

However, that is just putting off today’s problem until tomorrow, and that’s hardly an effective way to manage public policy. And it is a growing problem.

Estimates tabled in the House of Commons last June showed that more than 20,000 Canadians had been charged with simple pot possession since the Liberals took office in the fall of 2015. Of those, about 2,000 were convicted. Extrapolate those numbers to account for another 12 months of enforcement activity, and you have a very real possibility of 30,000 charges and 3,000 convictions.

The really frustrating thing is that, with a bit of additional work, the government could have encouraged provinces and municipalities into taking steps to avoid charging people for doing things that will soon become legal.

Although the federal government ultimately controls criminal law, the provinces and municipalities largely control enforcement. That creates an opportunity for those lower levels of government to ease off the laying of charges under the old law to avoid the spectacle of prosecuting someone for an offence that is no longer an offence.

This is largely what has happened in Vancouver, where a municipal bylaw was established to license pot dispensaries that would otherwise be illegal under federal law. This was accompanied by a policy whereby Vancouver police, in most instances, stopped charging people for simple possession.

The bylaw allows Vancouver police to focus their attention on unlicensed dispensaries and fine them up to $1,000. Licensed dispensaries can be fined as well if they operate too closely to schools and playgrounds. A similar approach in other urban communities could have dramatically reduced the number of people being charged and convicted.

Trudeau could also have struck agreements by using the Contraventions Act, a federal law that allows the feds to authorize provinces to issue tickets instead of laying charges for breaching federal statutes.

The point is that there are mechanisms that would have allowed the government to continue enforcing the old law without resorting to criminal charges. It would have been a steep hill to climb, given the differing levels of concern among provinces and municipalities about the prospects of legal pot. But it was certainly worth a try.

When you look at all the issues at play, the continued prosecution of people for possession of small quantities of weed is completely contrary to all the things the prime minister has said about the pointlessness of giving someone a criminal record for simple possession.

But then again, “unbelievable” is a word that is frequently and appropriately applied to the world of politics.

dan.lett@freepress.mb.ca

Born and raised in and around Toronto, Dan Lett came to Winnipeg in 1986, less than a year out of journalism school with a lifelong dream to be a newspaper reporter.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.