Soul food A tortured Anthony Bourdain served comforting humanity, one beautiful bite at a time

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/06/2018 (2735 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

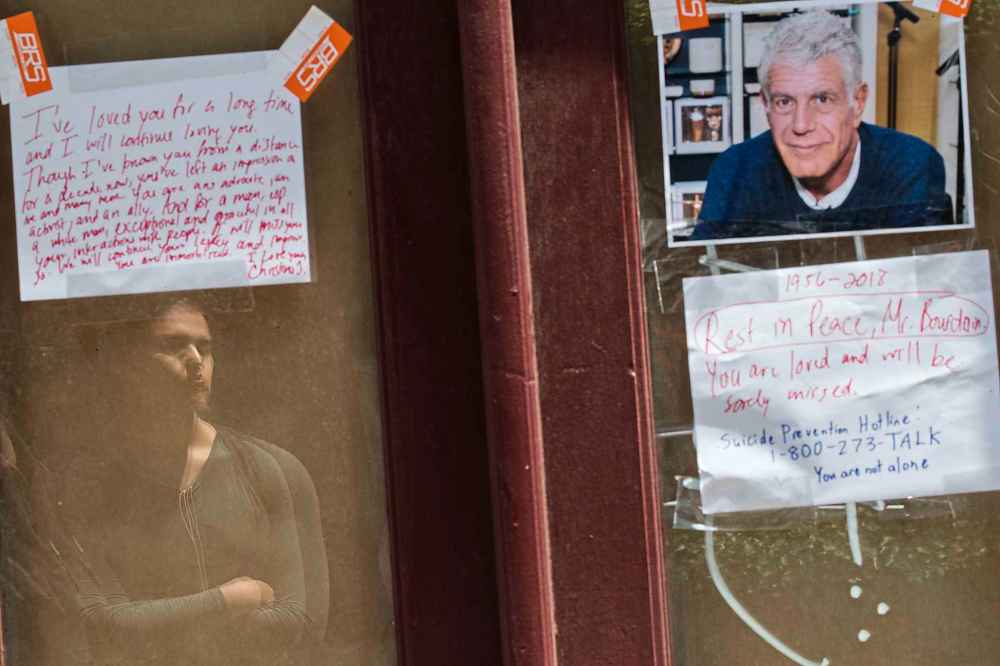

In retrospect, Anthony Bourdain warned us how his story might end. All the many times he wrote about his past flirtations with suicide, every time he joked about his own death, he was trying to tell us something about hurting.

All these years, I read and heard those things, lingering like minor chords strummed underneath a brighter song. Still, it seems I never really listened. So when he died, I could not write, reduced instead to sobbing in my bed.

It’s been a week since then. News sped by in breathless patches: Trudeau, Trump, a “special place in hell.” North Korea, Trump again, children in border detention. With each headline, I wondered what Bourdain would have said.

Maybe I can write now. For all he gave to me, from a distance, maybe I can do this one thing for him.

My affinity for Bourdain began the same way his unlikely media career did, in print. In 2001, a chef friend loaned me her copy of Kitchen Confidential, a smeary, bleary-eyed memoir about life in New York’s restaurant business.

At the time, I had no particular interest in a chef’s life. But I was captivated by Bourdain’s razor-sharp prose, relentlessly unpretentious, drenched with just the right amount of rock ‘n’ roll. I devoured the book in one day.

What I saw then, and still see now, was that Bourdain had a rare sort of voice. He saw the world as it was, and embraced its rawest edges. I would follow him through his subsequent books, and then his early forays into TV.

Yet when Parts Unknown debuted in 2013, I couldn’t resist making a snarky comment about the show’s title. Something about how strange it was that all these unknown parts seemed to be known by millions of people.

The assumption I made then, which I regret now, is that Parts Unknown — bankrolled by CNN — would be yet another travel show that traipsed through the world as an outsider, flattening lives into the other, the “exotic.”

I should have had more faith in him. For the last five years, and 11 seasons, Parts Unknown was the favoured ritual of my weekends. “There’s a new Bourdain” became the most romantic thing my partner and I could say.

What made Bourdain special was not just his talent as a storyteller, which was significant, but his instinct for compassion. Food was the heart of his work, not because he was a cook, but because it is the most human.

It’s instructive, perhaps, that he did not become famous until he was in his 40s. For most of his adult life, he had lived on the fringes: broke, working long nights, sweating it out alongside a cadre of undocumented immigrants.

This experience, and a natural comfort with what is honest, imbued Bourdain with an affinity for the people and places unloved by power. He treated grandmothers with the respect others accord mostly to world-class chefs.

In his most recent trip to Hong Kong, he hung out at a restaurant frequented by asylum-seekers in limbo. In Houston, he went not to cowboys, but to diasporic cultures thriving in a deep-red state: Vietnamese, Indian.

Over the years, his shows took him to Cambodia, and Libya and Laos. He went to the places Western media typically write off as too dangerous, too dark, too fraught; the Bad Places, filled by not-quite-human people.

Bourdain went to those places. He had beers on porches and ate fried fish and swapped jokes that withstood translation. He asked people about the past and the present, and their hopes for the future.

And he listened.

Consider his 2014 episode in Iran. At the time, virtually no Western news media was making a compassionate argument against sanctions; coverage of the country still bears the whiff of the Bush-era epithet, an “axis of evil.”

In one hour of food and friendly conversation, Bourdain peeled back the cruel artificiality of that division. He joined families for dinner, and shared their laughter. He ate take-out pizza with fashionable kids in the hills above Tehran.

Name one show in mainstream Western media that treats Iran as a real place, populated by normal people. People who go bowling, have friends over for dinner and eke out a life within the limits they are given.

What Bourdain understood, intensely, was that every story has two critical components, and one cannot be told without the other. There is news, the natural or political typhoons that storm through; and then there are people.

People, navigating through gusts of news, their lives a boat on an angry sea. People who have somewhere between little and no power to change events around them, only to hold onto the ropes, desperately trying to stay afloat.

And people are, for the most part, the same everywhere. They work, they raise their kids, they try to keep their families safe. They gather with friends to share cold drinks on hot nights. That is our shared heritage; that is life.

That this message was carried on CNN issued a tacit challenge to how news too often describes the world. The message was not always heeded, but the contrast between Bourdain and the news around him was unmissable.

Every day on cable news, a small army of talking heads is mixed and matched for maximum political friction, then trotted out to sell their side’s vision. Who we should trust, who we should fear. Who we should bomb or sanction.

And every time the news uncritically repeated the escalating political rhetoric of dehumanization — about “illegals,” about Muslims, about who to blame for all our problems — the refuge Bourdain scraped out became more clear.

What he called us to remember, both in and outside of news media, comes down to a simple question: whose side are we on? Do we swear fealty to the news, repeating it without thought? Or do we cast our lot with fellow people?

When Bourdain died, grief poured out from all corners of the world. Eulogies from Gaza and Iran and Vietnam. From the Philadelphia ‘hood and the Canadian North. All of them, in different words, expressed the same feeling.

Thank you for showing us as we are, they said, in one way or another. Thank you for letting us be seen.

This is Bourdain’s legacy, and what we ought to learn from his example. He warned us that his voice would not stay forever, or even for very long; but first, he showed us that we cannot tell the truth of things if not with love.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.