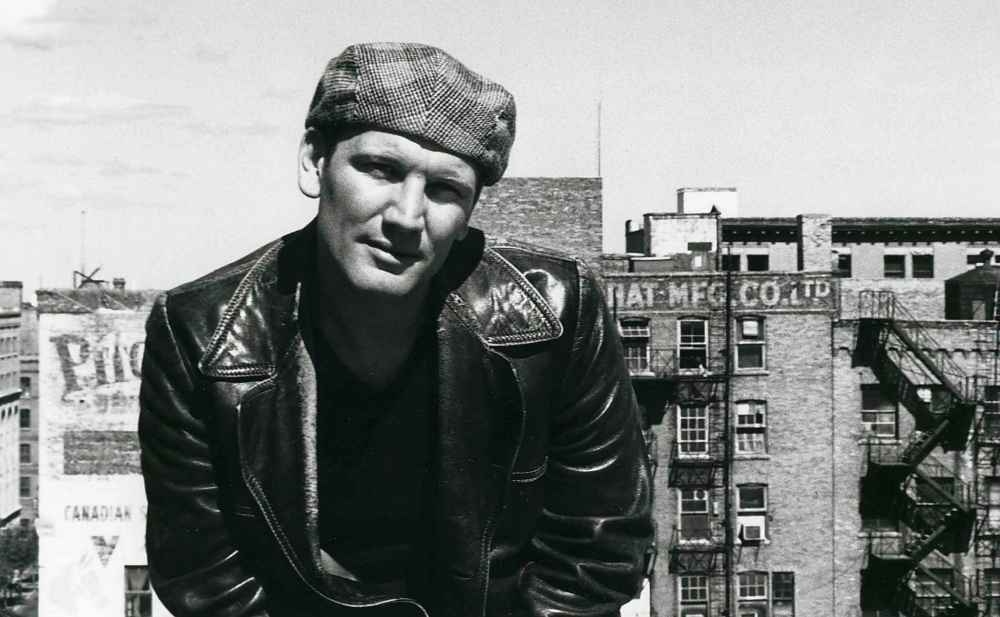

Back in the ring Roots-rocker Mark Reeves is working on his first album in 17 years and knows a song about Winnipeg boxer Donny Lalonde is a knockout

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 31/07/2020 (1957 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In June, a group of Free Press writers, myself included, put together a comprehensive list of what we determined to be Manitoba’s 150 most important, homegrown songs in a nod to the province’s sesquicentennial.

Free Press staff pick Manitoba's 150 top songs

Posted:

Back in 2017, a crew of musically inclined Free Press staffers and freelancers was asked to create a list of Canada's 150 most important songs, in honour of our fair country's sesquicentennial anniversary.The process was long and arduous, and though we were all ultimately incredibly proud of the outcome, we had little desire to take on a project of that magnitude again.

While it’s a little soon to start contemplating a followup piece — I’ve suggested we wait until 2070 when the province turns 200 and I hit 108 — it’s a safe bet a tune currently in the works, one with as local a flavour as Gondola pizza and Fat Boys, would be part of the mix.

“I’m excited about this one because honestly, how often do you work with a topic nobody’s written a song about before? Especially one with such strong ties to the community,” says Mark Reeves, 52, a seasoned roots rock musician once described in a press release as, “if Bonnie Raitt and Lyle Lovett had a love child, Mark Reeves would be it.” (“Yeah, that’s weird,” he agrees when a reporter points out that characterization may be a bit out of whack given Lovett is only 10 years older than him.)

The composition-in-question, with the working title That’s the Day I Fought Sugar Ray, revolves around the Nov. 7, 1988 light heavyweight title bout between Winnipegger Donny (Golden Boy) Lalonde and Sugar Ray Leonard.

Reeves, a lifelong boxing fan, began penning it in April while he was holed up at his cottage in the Interlake, a few weeks after he cheekily thanked an audience for risking their lives to take in his set at Gimli’s Ship & Plough Tavern days before public spaces across the province were shuttered owing to COVID-19. Musician friends who’ve heard snippets of That’s the Day… have already likened it to Hurricane, Bob Dylan’s mid-70s ode to American boxer Rubin (Hurricane) Carter, wrongfully convicted of murder in 1967. Reeves begs to differ, telling them that comparison doesn’t really apply.

“My angle is what an interesting, epic moment in Winnipeg history it was when the Golden Boy, a local guy from ‘just over there,’ fought this absolute legend in Sugar Ray,” he says, noting while he didn’t see the fight the night it occurred — Leonard won the hard-fought battle in the ninth round via TKO — he’s since viewed it numerous times on YouTube.

“The only thing I wish is that it had been held in New York City instead of Las Vegas, because as I’m writing it, that’s what I see in my head: Donny in the streets of New York, preparing for the fight of his life,” he continues, promising the number will be completed in time to appear on his soon-to-be-released new album, his first since 2003.

“I still want to talk to (Lalonde) to pick his brain a bit about what happened that day but I’m pretty pleased with it already. Every so often you know a song is going to click the second you start writing it. That’s definitely been the case here. I can’t wait to play it live.”

● ● ●

Reeves, who lives two doors down from his childhood home, steps away from Windsor Community Centre, says, “Ha, you’re right. I never really thought of it that way,” after being congratulated on 40 years of playing guitar, seconds after he mentions picking up the instrument for the first time at the age of 12. Here’s the thing, though: Reeves, a veteran of seven Winnipeg Folk Festivals, two of which involved his blues-soaked, back-up band the Groove, can’t remember a time when music wasn’t part of his life. That’s thanks in large part to his father Doug, who used to wake the house up bright and early every Saturday with whatever slice of vinyl he was in the mood for that morning.

“Sleeping in wasn’t an option. By 8 (a.m.) at the latest he’d be downstairs blasting Pat Metheny, Tom Jones, the Commodores…. His taste was all over the map and we never knew what was coming next,” he says with a laugh, citing a Father’s Day playlist he recently put together in honour of his dad, who died in 1999. “I included Willie Nelson’s Always on My Mind on it because I distinctly remember how he used to lovingly sing the (crap) out of that song to my mom, meaning every single word.”

On Aug. 16, 1977, Reeves, nine at the time, and his brother Leon, four years his senior, were hanging around at Kildonan Park. Their mother had dropped them off there for the day while she went to work, “back when you could get away with that sort of thing,” he says with a wink. The pair had brought along a battery-powered transistor radio and just after 3 p.m. a disc jockey announced that Elvis Presley had died of a heart attack at his home in Memphis. Reeves remembers spending the two hours until their mother picked them up sitting on the grass, listening to one Elvis tune after another on the radio.

“That was the spark, hearing all his amazing Sun sessions stuff like Heartbreak Hotel, Blue Suede Shoes and Hound Dog. Hell, I might as well have been transported back to 1956 right then and there, I was digging it so much. That night, over dinner, I told my parents I needed a guitar. To which my dad replied, ‘In that case, you’d better save up.’”

Two years and $215 later, money he procured largely by returning empty pop bottles for two cents apiece, he bought an acoustic guitar from a woman at church. She threw in a few free lessons but not wanting to play “Little Brown Jug for the rest of my life,” he switched to a teacher who shared his passion for rock ‘n’ roll.

“Mark started with me at Major & Minor Musical Supplies, at the corner of Marion and Des Meurons. He would have been about 13 and I was about 18,” says Ken Roberts who, around the same time, was fronting a Windsor Park-based band dubbed Four on the Floor.

“Our initial lessons consisted of the usual music lesson stuff — reading, learning the fretboard, etc. Mark was a very good student because it was obvious he wanted to be there. A lot of kids get sent by their parents for something to do, but not him. His enthusiasm was always upper echelon. He had a drive for music that you need to succeed in the business, and you can’t teach that.”

“He (Reeves) had taken up the harmonica, as well, and had become quite proficient on both instruments, to the point that we’d play blues jams, trading leads with Mark playing the harmonica. My mum says she couldn’t get the dishes done because she was dancing around the kitchen too much.” – Ken Roberts

Roberts quit his teaching job after netting a full-time job at CN but a couple of his students, Reeves among them, persuaded him to continue teaching from his parents’ home.

“By that time Mark had gotten heavily into the blues, which I, of course, encouraged. He had taken up the harmonica, as well, and had become quite proficient on both instruments, to the point that we’d play blues jams, trading leads with Mark playing the harmonica. My mum says she couldn’t get the dishes done because she was dancing around the kitchen too much.”

Obviously a quick study, Reeves began playing at various downtown coffee houses at age 14. He was busking on Portage Avenue in 1983 when a person responsible for booking acts for an outdoor venue near what is now Portage Place asked if he was interested in a time-slot.

“I jumped at the chance, and as I watched him write my name down in a calendar I was like, ‘Wow, I think I just made it.’” Pausing to reflect, he says his set that day likely consisted of a few Neil Young songs interspersed with an original tune or two, perhaps the first song he ever wrote titled Blues in Her Blood. “Or maybe it was called Blues in My Blood, I’m not too sure.”

After graduating from Glenlawn Collegiate, where he played in the high school jazz band, he took a year off to travel. That is, when he wasn’t participating in weekly blues jams at the Viscount Gort Hotel hosted by Big Dave McLean, one of his idols. He moved to Boston in 1987, having landed a scholarship to the Berklee School of Music. He still had one semester to go during his second year there when he packed his bags and caught a flight to Europe. His reason for leaving? He didn’t want to learn how to be a songwriter, he says matter-of-factly. He wanted to “live how to be a songwriter.”

Reeves returned to Winnipeg in 1989, at which point he embarked on what he jokingly refers to as his prolific period. In the span of 13 years he wrote and recorded six albums, three that were released on cassette and three on CD. When he wasn’t in the studio he was criss-crossing the country, performing at outdoor music festivals or opening for the likes of Robert Cray, Colin James and Jesse Winchester.

In 2007, four years after the release of Sure is a Pretty Name, an album that drew favourable comparisons to John Hiatt and Ry Cooder — “honest, Springsteenesque roots-rock,” read one review — Reeves was in a boating accident in Ontario that caused him to lose feeling in his fingers. Around the same time he went through a divorce, a set of circumstances he admits threw him for a bit of a loop.

As soon as things began to settle down, Reeves, who names singer/songwriter Paul Williams, he of Phantom of the Paradise-fame, as a major influence (“I was initially disappointed when my parents gave me his greatest hits album for Christmas, because I was into heavier stuff, but the songs, my God”), hit the road again. The father of one daughter never stopped writing, but for whatever reason he avoided putting anything down on tape. That is, until about 10 months ago.

“Everything from that new Donny song to ones that are two, three… as much as five years old,” he says when asked what fans can expect to hear on his upcoming release, which he refers to as an album, whether or not a physical copy ever sees the light of day. “I mean, even if it’s just available for download, what am I going to say when I play the songs live? ‘Here’s something from my new file?’”

Reeves, rarely seen on stage these days without his trademark bowler hat, which he “borrowed… OK stole” from his agent’s husband about five years ago, has played in front of an audience a couple of times since the provincial government relaxed certain rules regarding public gatherings.

John Scoles, owner of Times Change(d) High and Lonesome Club, is doing everything he can to grant Winnipeggers another opportunity to catch Reeves sooner rather than later, hopefully at the Beer Can, a pop-up beer garden on Main Street that began showcasing live acts in mid-June.

“I suspect it will be a weekend afternoon, we’re just trying to nail down a day,” says Scoles, who’s been helping book acts for the unique venue, located steps away from Times Change(d) in vacant parking lot.

Scoles guesses it was 1992 or ‘93 when he caught Reeves at Times Change(d) for the first time.

“When I started going there Mark was one of the quote-unquote stars of the place, along with Big Dave (McLean). He travelled a lot in the ensuing years and didn’t play there as much as he once did but after I took over we were able to reconnect.”

“He’s the same as he’s ever been. He absolutely glows onstage. He has fantastic stage presence and brings it every night. That’s his style. He can’t do it any other way. He’s definitely someone Winnipeggers should be proud to call their own.” – John Scoles, owner of Times Change(d) High and Lonesome Club

Reeves last played Times Change(d) in February. Given the way he interacted with the crowd that night it could have been 1995 all over again, Scoles says.

“He’s the same as he’s ever been. He absolutely glows onstage,” Scoles says. “He has fantastic stage presence and brings it every night. That’s his style. He can’t do it any other way. He’s definitely someone Winnipeggers should be proud to call their own.”

“I think the biggest compliment I’ve ever received is, ‘Man, you played that song like it was the first time you ever played it,’” says Reeves, also an accomplished producer who has worked with the likes of Jodie Borle and Keith Macpherson.

“The thing is, I’m not doing 250 dates a year, so the songs stay relatively fresh. Plus there’s a lot more to pick and choose from nowadays.”

Promising not to make his fans wait another 17 years between new releases – heck, he has an entire album’s worth of country-tinged tunes in the bank, ones he initially meant for one record or another but left off at the last second — he says there is one gig coming up that will mean the world to him. On Aug. 14 he’ll take part in Gerryfest, in honour of his dear friend Gerry Atwell, who died of a heart attack in November. The affair is scheduled to take place at the St. Norbert Arts Centre on what would have been Atwell’s 61st birthday.

“I’d definitely thought about it before, what a gift it’s been to be able to do my own thing all these years. But I thought about it again in the days after Gerry passed,” he says, his voice dropping off a bit. “My parents used to get on me, telling me I needed a degree to be successful. But if I’d listened to them and gone that route none of this would have happened. It’s been a wonderful journey and I wouldn’t trade a second of it.”

david.sanderson@freepress.mb.ca

Dave Sanderson was born in Regina but please, don’t hold that against him.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.