Go Blue… grass! We talk to five of Winnipeg's best banjo players to get in the right mood for the annual gridiron hoedown with our hillbilly next-door neighbours to the west

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 06/09/2019 (2292 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It was the shot heard round the world. Or at the very least, across Canada’s two easternmost Prairie provinces.

In 2003, days before the Winnipeg Blue Bombers and Saskatchewan Roughriders were due to lock horns in the Canadian Football League’s Western Division semifinal match, Bombers placekicker Troy Westwood fuelled that tilt’s already raging fire when he famously referred to Riders devotees as “a bunch of banjo-pickin’ inbreds.”

Westwood, now a sports radio host for TSN 1290, softened his stance later that week, acknowledging he may have spoken out of turn given “the vast majority of people in Saskatchewan have no idea how to play the banjo.” Still, ouch.

In early 2004, Winnipeg-born musician Robert Allan Wrigley and his wife Bobbi-Jo were living in Victoria when they learned they were expecting twin boys. Wanting to be closer to family when their babies arrived, they moved back to Winnipeg that summer. Soon, Wrigley, an accomplished guitar, mandolin and banjo player, began hearing radio commercials advertising the inaugural Banjo Bowl, the tongue-in-cheek, Westwood-inspired tag Bombers brass had chosen to adopt for the annual Bombers-Riders rematch scheduled the week after the Labour Day Classic in Regina.

While in B.C., Wrigley hadn’t heard boo about “Troy Westwood and banjos and stuff.” So his initial thought when the ads aired was, “What the heck’s a Banjo Bowl?” His second thought: “I bet they’re going to need some banjos.”

Wrigley called the Blue Bombers front office, informing the person who answered the phone if the club was looking for somebody to play some banjo to help sell tickets, he was their guy. Days later, there he was, at an official news conference in the Blue and Gold Room performing Foggy Mountain Breakdown for a flock of television, radio and newspaper reporters.

“They brought me back for the game as well,” Wrigley says, seated in a lawn chair in his backyard. “They set up a stage with this huge PA system in the south end zone and the band I was in at the time, the Pines, was the featured entertainment. That was a heck of a lot of fun, no doubt about it.”

This year’s Banjo Bowl, set to kick off at 3 p.m. Saturday at IG Field, marks the 15th anniversary of the perennially sold-out contest. To toast that milestone, we reached out to five of Winnipeg’s most talented banjo players, including Wrigley, asking if we could pick their brains a bit about their chosen instrument, as well as the Banjo Bowl itself.

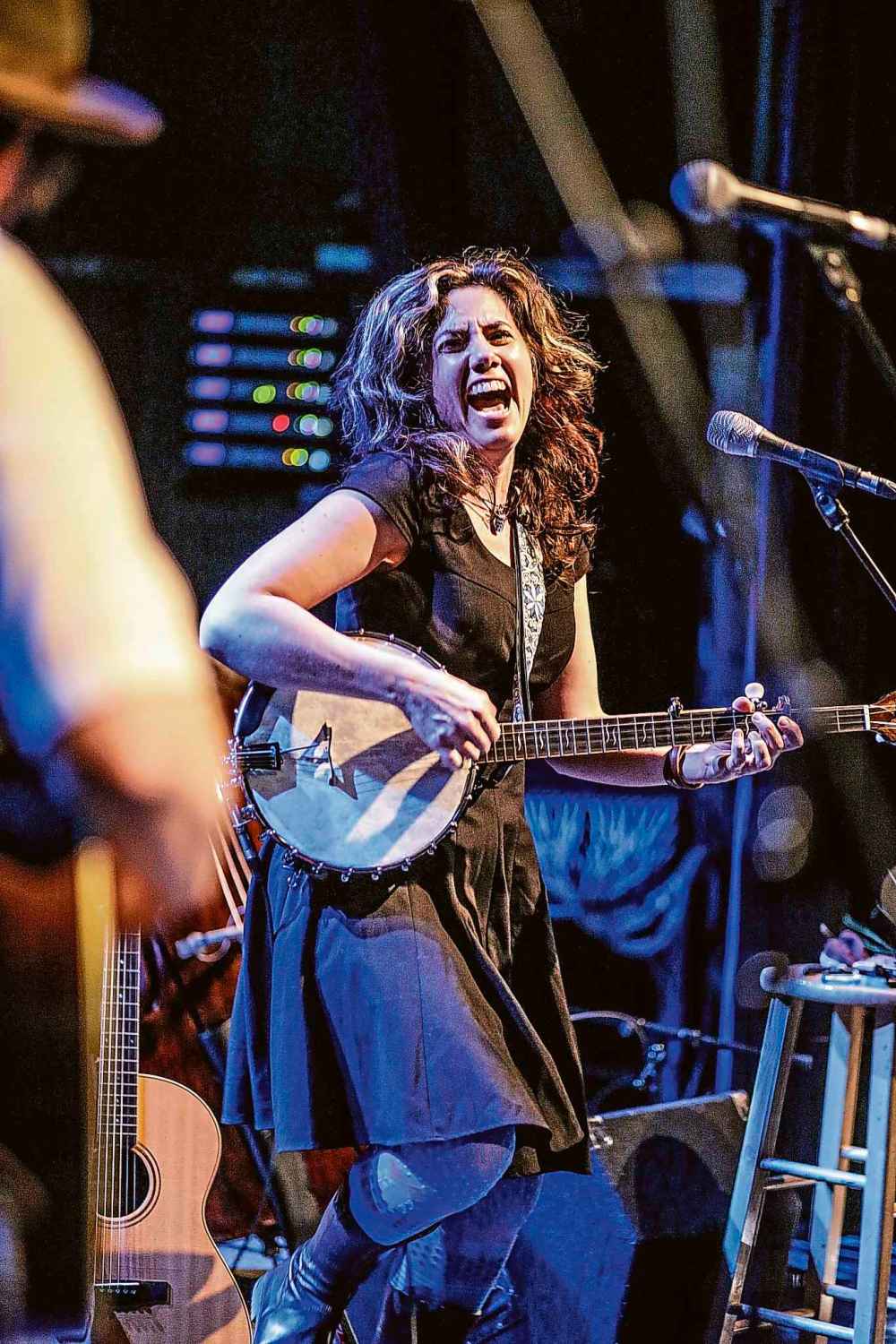

Not to jump too far ahead, but the best response in regards to the latter definitely came from Cara Luft, a founding member of Juno Award-winning folk and bluegrass group the Wailin’ Jennys and, together with J.D. Edwards, currently one half of roots-rock duo the Small Glories. Referring to herself as “not much of a sports fan,” Luft let out a loud guffaw, admitting her reaction when she first heard the term Banjo Bowl was something along the lines of, doesn’t that sound like a blast, a bunch of banjo players getting together to go bowling.

“Obviously, I later learned it had to do with football, but if you’re asking me, I almost like my idea better,” she said, laughing a second time.

JAXON HALDANE

In the early 1990s, Gimli-born Jaxon Haldane, the 43-year-old, banjo-playing lead vocalist of the D. Rangers, a Winnipeg band whose sound has been described as “mutant bluegrass” and “arm-swinging hillbilly-stomp,” was drawn to Seattle bands such as Nirvana, Pearl Jam and Alice in Chains.

Grunge was the primary reason why Haldane picked up a guitar in the first place at the age of 15, and also why he joined a rock band — Miss December, he recalls with a smile — while living in Kenora, where he spent his high school years.

Haldane’s interest in the banjo started as a fluke. When he was 17, his mother, a stained-glass artist, brought one home for him after accepting it in trade for one of her glass pieces.

“Knowing I had expressed interest in busking and was starting to get into acoustic instruments, one day she was like, here you go,” he says, seated in a Portage Avenue coffee shop a few blocks from his home in the West End. “It was a used banjo, not a particularly good make, but it was definitely enough to get me started.”

Not long thereafter, Haldane began volunteering for a music organization in Kenora that staged folk concerts in and around the Lake of the Woods community. He struck up a friendship with a seasoned musician whose skill on the banjo impressed the teenager to no end.

“I was so far beneath his level that I could really just watch from afar and be inspired. But through him, I got turned onto all these bluegrass festivals and almost overnight, that changed everything,” he says.

Haldane’s parents moved to Oklahoma when he was in his early 20s. Whenever he went to visit them, he made a point of popping into the Double Stop Fiddle Shop, a music store owned and operated by Byron Berline, a revered bluegrass fiddler who has recorded with a who’s who of musicians, among them Bob Dylan, Willie Nelson, the Eagles and the Rolling Stones.

“I can’t tell you how crazy it was to have access to this legend. I mean, to be able to sit around his shop all day, playing music and listening to him tell stories about performing with the Byrds and the Flying Burrito Brothers…. My mind was getting blown on a regular basis.”

“You see shoulders perk up, smiles break out on people’s faces…. The ability to lift people is definitely a musical characteristic the banjo can lay claim to.” – Jaxon Haldane

By 2000, Haldane had largely parked his electric guitar in favour of the banjo. Starting to find his voice as a songwriter, he openly wondered what he and others his age had to offer the world of rock now that, in his mind, “every avenue in that style of music had already been explored.”

“I think that’s what drove a lot of us to look back on some of the people and styles that influenced rock and roll, thinking perhaps if we could better understand guys like Bob Wills, Bill Monroe and Hank Williams — the original punk rockers — then we’d have a better foundation for saying something relevant within that genre,” he explains. “Almost overnight, all I wanted to do was sing three-part harmony and learn all the different mechanics of the banjo to recreate the sounds that were going around in my head. And because I wasn’t the only one thinking in those terms, it was relatively easy to find people to collaborate with.”

Haldane has recorded three albums with the D. Rangers, three more as a solo artist. He says there’s little doubt about it, when he’s on stage “ripping” through an original tune or cover of, say, AC-DC’s Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap on banjo, it immediately raises the energy level of whatever room he and his bandmates find themselves in.

“You see shoulders perk up, smiles break out on people’s faces…. The ability to lift people is definitely a musical characteristic the banjo can lay claim to,” he says, citing the late John Hartford, composer of Gentle on my Mind, a smash hit for Glen Campbell in 1967, as one of his primary influences.

Haldane, who once wrote “Sack Troy Westwood” in felt pen on his banjo, similar to how Pete Seeger inscribed, “This machine surrounds hate and forces it to surrender,” on his long-neck banjo in support of the ’60s civil rights movement, is far less enamoured with the hoopla surrounding the Banjo Bowl than the instrument it’s named for.

“I’m curious why there hasn’t been a more thoughtful piece done about the origin of the game, in the context of our modern move towards bigot egalitarianism,” he says, polishing off the last of his tea. “I think the Banjo Bowl was born of essentially a classist slight or slur which, at the time, I felt was not a very classy thing for a professional athlete to say.

“And then to see the city and the league run with it? I do find it surprising that here we are, in a completely different world than we were in 2004, and we still have nobody calling attention to the fact this event was born of a borderline racist comment. It’s a bit of an elephant in the room for some of us, for sure.”

Lately, Haldane has been devoting a fair bit of time studying New Orleans jazz piano giants such as Professor Longhair and Dr. John, in an attempt to add banjo parts to some of their compositions. (Guaranteed to be a hoot when played live, he and the D. Rangers are putting the finishing touches on a bluegrass version of Devo’s Jocko Homo.)

“I’ve found a way for the banjo to be relevant in different styles of music. For example, even though it’s difficult to sound sad on the banjo, I love playing it on a slow song. I think it was Rob McCoury, son of Del McCoury, one of the great, modern-day banjo players, who said you don’t learn to play banjo, the banjo teaches you how to play it. That’s so, so true.”

CARLY DOW

Carly Dow, whose 2018 album Comet has drawn comparisons to 1970s-era Fleetwood Mac, says she was a bit of a late-bloomer, music-wise, given she was already in high school when her parents signed her up for piano lessons.

“Forced me to sign up is probably more accurate,” says Dow, 31, who grew up in St. James but presently lives in Kaslo, B.C. where she works as a plant biologist.

A quick study, she eventually moved from piano to guitar to banjo, the latter of which she latched onto after coming across a video of Abigail Washburn, an American banjo player and singer, performing Nobody’s Fault But Mine, a track from the Illinois-born, Nashville-based artist’s critically-acclaimed 2005 album, Song of the Traveling Daughter.

“Later I saw a video for another of her songs, City of Refuge, and that was it, I was sold,” says Dow, who taught herself to play largely by watching YouTube.

Like Washburn, Dow plays clawhammer-style banjo, which she describes as, “shaping your hand like a claw, just the way it sounds, and using only your thumb and index finger to pick the strings.” Other clawhammer banjoists include Ralph Stanley, Neil Young and actor/comedian Steve Martin, whose album The Crow: New Songs for the 5-String Banjo won the 2010 Grammy Award for Best Bluegrass Album.

“It totally looks crazy when you don’t know what the technique is — in particular when you see somebody playing fast — but it’s mostly muscle memory on your right hand, so once you get the hang of it, it all kind of falls into place.”

In 2017, Dow was a featured entertainer at the Winnipeg Folk Festival. She performed a solo set on the Little Stage, and also took part in a banjo workshop on the Shady Grove stage with Danny Barnes (Bad Livers), Old Man Luedecke (2009 Juno Award-winner for traditional folk album of the year) and Jayme Stone (2013 Canadian Folk Music Award-winner for Instrumental Artist of the Year). She was the only woman invited to take part and afterwards, a slew of teenage girls approached her with questions about the banjo.

“That was just so wonderful,” she says, listing fellow Manitobans Cara Luft, Ruth Moody and Allison de Groot as three “incredible” female players she enjoys listening to. “I still play a fair amount of guitar, too, but I get extra-excited when people want to talk about the banjo because I think the more joy you can spread with it, the better.”

That said, she agrees Not a Songbird, a track from her 2015 debut album Ingrained, isn’t exactly your typical, joyful banjo tune. A slow number, it starts off sombre and remains that way for its 3:53 duration.

https://youtu.be/8NVT_SsCeK8

“I always say you can play devastatingly sad songs on the banjo as well as ones that are super-cheery, which is what makes it such a unique instrument, it’s just so versatile,” she says.

Dow owns two banjos, a Rickard banjo purchased from the manufacturer’s shop in Aurora, Ont. that she writes and performs with, and a “beater-model” she happily lends to people who express an interest in learning how to play. Besides presenting her own tunes in concert, she enjoys experimenting with songs she grew up with, as well.

“Lately I’ve been learning some Rage Against the Machine on banjo. It’s been sounding pretty cool, actually, as they’re super-groovy tunes when you break them down enough,” she says.

While she isn’t “some diehard sports nut,” she says the Banjo Bowl is on her radar, in particular, Westwood’s original insinuation it doesn’t take a lot of brains to play the banjo.

“The whole, hillbilly stereotype around the banjo is kind of interesting to me. Obviously, stereotypes are there for a variety of reasons but in actuality, the banjo is a pretty complex instrument. Obviously, not everybody who plays it is some total redneck, the way he made it sound.”

DANIEL PÉLOQUIN-HOPFNER

Daniel Péloquin-Hopfner, who plays mandolin, lap steel, banjo and organ for the folk/roots outfit Red Moon Road, laughs when he is asked whether the proper term for a person who plays the banjo is banjo player or banjoist.

“It’s probably better if you just write masochist,” says the 33-year-old multi-instrumentalist, catching his breath after riding his bike to a downtown interview from his home in St. Boniface.

Péloquin-Hopfner, born in Ste. Rose du Lac, grew up listening to his parents’ record collection, well-stocked with LPs by the likes of Joni Mitchell, Joan Baez and Bob Dylan. He started playing piano when he was three and switched over to guitar in junior high.

In 2012, he and Daniel Jordan, Red Moon Road’s lead guitarist, were writing songs together when Péloquin-Hopfner felt a tune they were working on, Do or Die, “needed something to drive it along.”

“At first I was thinking a tambourine — something to do with sixteenth notes — then I changed my mind and said, ‘No, what this needs is banjo,’” he says.

One problem: neither he nor Jordan owned a banjo, or knew how to play one.

“It looks effortless but God, it’s so hard. It’s kind of a silly instrument in the sense the lowest note is not the closest string to your body, the way it is with a guitar. You have to pretty much unlearn all the finger-style work you already know. It was absolutely humbling and annihilated my ego, but for the best.” – Daniel Péloquin-Hopfner

Not wanting to commit to the instrument too much, Péloquin-Hopfner rented a banjo instead. He spent three weeks trying to learn its ins and outs, which proved to be a lot more difficult than he’d anticipated.

“It looks effortless but God, it’s so hard,” he says, leaning back in his chair. “It’s kind of a silly instrument in the sense the lowest note is not the closest string to your body, the way it is with a guitar. You have to pretty much unlearn all the finger-style work you already know. It was absolutely humbling and annihilated my ego, but for the best.”

Péloquin-Hopfner didn’t end up recording the banjo parts for Red Moon Road’s eponymously-titled debut album — friends of the band handled those duties, instead — but by the time the group was ready to hit the road to promote their record, he felt comfortable enough to play in front of a live audience.

“There’s no better way to test your mettle than in the heat of battle,” he says, citing Noam Pikelny, banjo player for Brooklyn-based, progressive bluegrass band the Punch Brothers, as one of his idols.

In 2015, Péloquin-Hopfner, who plays a Great Lakes Banjo Co. banjo built in 1976, was one of a handful of banjo players hired by the Blue Bombers to entertain the 30,000-plus fans in attendance at that year’s Banjo Bowl. Dressed in overalls and sporting blackened-out front teeth, he wandered the concourse before, during and after the game, taking requests. (You might think it’d be impossible to play The Imperial March from The Empire Strikes Back on the banjo but you’d be wrong, he says with a chuckle.)

“I come from a theatre background so I kind of leaned into the gig a little bit,” he says, calling the 1972 film Deliverance, which spawned the Top 10 hit Dueling Banjos, “probably the worst thing that ever happened to the banjo.”

“I had a clear idea of what I was being hired to do and treated it like Halloween because let’s face it, at the end of the day, everybody there was just looking to have a laugh.”

On a more serious note, last fall Péloquin-Hopfner took part in a concert toasting the 50th anniversary of Le 100 Nons, a non-profit organization that promotes Manitoba’s francophone music industry. At one point, he introduced a poem written by Métis leader Louis Riel that he had set to music. Well, sort of.

“It was something Riel had written while he was in jail, so I imagined myself sitting in a cell with these concrete walls and steel bars, as I tried to recreate that feeling of loneliness,” he says. “I sang the words into the banjo and the resonation made it sound cavernous. Also, instead of playing the strings, I raked my fingers across the strings between the saddle and the tailpiece, just kind of plinks and plunks, which to me sounded like somebody raking a metal cup back and forth across steel bars. It turned out to be a pretty powerful piece and could well be the best thing I’ve ever done.”

CARA LUFT

Calgary-born Cara Luft, 45, can’t recall a time when music wasn’t part of her upbringing.

Her parents Barry Luft and Lyn Harbaugh, both of whom are revered members of Alberta’s folk music community (her dad reportedly taught Grammy Award-winner Cathy Fink how to play banjo), have always been “big believers in a good song is a good song, no matter who wrote it,” and almost always had something ear-catching spinning on the family turntable, Luft says.

“They were of the Hootenanny-era, and were immersed in the labour movement: Pete Seeger, the Weavers, Woody Guthrie etc.,” she continues when reached by phone in Seattle, the Small Glories’ latest tour stop. “They were also big aficionados of British Isles trad and folk rock, so (they) played us lots of albums by Steeleye Span, Pentangle, the Young Tradition (and) Martin Carthy.”

Luft fiddled around with her dad’s banjo as a kid. But it wasn’t until the Wailin’ Jennys came along that she picked one up in earnest. In the mid-2000s she was living in Winnipeg, going through a painful breakup. Close friends with Daniel Koulack, whom she describes as one of the best banjo players in the country, she would often go to his place to “play music together and cry a little bit.”

“One time, he looked at me and said, ‘You know, Cara, the banjo can offer you a lot of healing,’ and heck if he wasn’t 100 per cent right. I would sit and play chords, over and over again, until I started to feel better,” she says. “The banjo is truly a mystical instrument and once I finally adjusted my brain from playing guitar for 20-plus years to playing banjo, I was off and running.” (Know how parents sometimes help their kids shop around for their first car so they don’t go home in a lemon? Luft had the same experience with the banjo. Her dad told her if she was going to learn to play “for real,” she needed a good one and went “halfers” with her on a custom-built model fashioned by a luthier in Guelph, Ont.)

Like Péloquin-Hopfner, Luft says she had to rethink pretty much everything she knew about string instruments when she took up the banjo.

“If I was picking on the guitar, my thumb would go down and my fingers would come up, that’s kind of the basic pattern,” she explains. “Whereas with clawhammer banjo, the style I play, my fingers are going down and my thumb is kind of bouncing out and up on the fifth string, so it’s very different and plays with your mind a fair bit.”

Years ago, Luft, Miss January in a 2017 fundraising calendar called Banjo Babes, heard about an anti-consumerism movement titled “Buy Nothing Christmas” started by a friend of hers, Aiden Enns. Inspired, she decided the best way she could do her part during the holiday season was by rearranging and recording Christmas carols on the banjo, and distributing the end-results to family and friends.

“I think my first one was a little-known French carol called Bring a Torch, Jeannette, Isabella,” she says. “I spent a week working on it, then sat with a little video camera, videotaping my performance and sending the video out to everybody. I did that for about five years running and is probably something I should get back to doing, it was so much fun.”

As for the Banjo Bowl, now that she understands there aren’t any strikes and spares involved, she has another idea.

“I secretly do love that the banjo is getting recognition but what would be even better was if folks at the games could hear some beautiful banjo and maybe even come to love it,” she says. “J.D. and I were just talking in the car on our drive today about how they should consider having a bunch of banjo players during halftime. Now, that would make for a spectacular game.”

BOB WRIGLEY

In 2005, the year after Wrigley performed at the inaugural Banjo Bowl, he received a call from the owners of the Viscount Gort. They wanted to know if he was interested in an encore performance, this time playing for people staying at the Polo Park-area hotel the weekend of the big game; the Bombers were playing at nearby Canad Inns Stadium — IG Field didn’t open until the 2013 season.

“They asked me to wander around the restaurant and bar Friday and Saturday night, playing songs and taking requests,” he says. “Then, on the day of the game, they rented a hayride wagon pulled by horses to take people to the game and I went along on that, too, playing banjo. A lot of the guests were from Saskatchewan, so for sure there were a few good insults fired my way. But do I remember any specifically? Nah. I just remember it as a pretty good time.”

Wrigley, 45, figures he was 12 years old when he taught himself how to play electric guitar. At the age of 28, by which time he had belonged to numerous rock bands, he caught wind of weekly bluegrass jam nights that were being held at a Royal Canadian Legion in Transcona. He headed there one evening and was instantly intrigued. When he was a kid, he used to listen to his father strumming an old harmony banjo in the basement from time to time so he gave him a call, asking if that instrument was still kicking around. C’mon over and get it, his dad told him.

Within a month or two, he was “completely obsessed” with the banjo, he says. At the time, he worked nights in a group home. For about a year his daily schedule consisted of arriving home at 7 a.m., wishing his wife a nice day on her way out the door to her 9-to-5 job, then heading into the living room to play banjo for hours on end.

“I really loved that acoustic freedom of not needing electricity to play, I thought that was cool immediately,” he says, when asked what appealed to him most about the instrument. “Plus there’s the speed involved. I’ve always liked to play fast, whether it’s guitar or bass, and on a banjo, you can play super-fast. It’s also the loudest of the acoustic instruments so, guaranteed, you’re always going to be heard.”

These days, Wrigley plays a Gold Tone five-string banjo in a pair of bands. One of them, Double the Trouble, features his twin 15-year-old sons, Luc and Aiden, on lead vocals and fiddle, while he handles guitar and banjo. (A well-travelled trio, Double the Trouble has performed as far south as Punta Perula, Mexico and as far north as Rankin Inlet.)

He also plays banjo for Stonypoint, which is an interesting story in itself, he says.

As a kid, Wrigley often attended the Winnipeg Folk Festival with his parents. What he remembers most about those experiences isn’t the campground or stage acts, it’s the walk through the parking lot on the way to the festival grounds where he and his parents would make a point of stopping to listen to a group of guys in their early 20s playing banjo for passers-by.

“I later found out they called themselves the Parking Lot Pickers,” he says. “Well here we are all these years later and two of those guys that were in the parking lot — Kenny Kansas and Ted Longbottom — now play with me in (Stonypoint).”

On the 15th anniversary of the first Banjo Bowl, Wrigley, who’s recently put the finishing touches on a banjo version of Pink Floyd’s Time (audience members don’t usually twig in at first, he says, but the moment he sings the opening line, “Ticking away the moments that make up a dull day…” their eyes light up), already has an idea what the Bombers should do for No. 16, in 2020.

“I was thinking we should all get together — as many banjo players from Winnipeg as possible — and present a night of banjo music somewhere like the West End (Cultural Centre) or Times Change(d) (High and Lonesome Club). I think it’d be a great idea to do it the Friday night before the game.

“Heck, we should book it right now.”

david.sanderson@freepress.mb.ca

Dave Sanderson was born in Regina but please, don’t hold that against him.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.