An outsider’s embrace

BBC reporter grew to love many things about Winnipeg but was struck by the city's stark racial divide during the months she spent here writing about Tina Fontaine, gathering material for new book

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 07/09/2019 (1973 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

When Tina Fontaine’s body was pulled from the Red River in August 2014, Joanna Jolly was 2,000 kilometres away, working on feature stories in the BBC’s bureau in Washington, D.C., where her journalism career had unexpectedly sent her.

She was there, when a Canadian colleague mentioned the case.

Another Indigenous girl killed, he said, and added another thought: Canadians are so racist.

Jolly was struck by the statement. She had grown up near London, travelled the world as a journalist, spent some time on the Canada’s East Coast and “absolutely loved it.” She’d known Canadians and liked them, and the thought of racism being pervasive in the country surprised her.

“I thought, ‘Hold on a sec,’” Jolly says, chatting over the phone from East Timor, where she had returned this week to mark the anniversary of the Southeast Asian country’s independence vote.

“‘Canadians? Racist?’ I’d always had the highest opinion of Canada… and also kind of looked at Canada as the kind of place you’d live if you could choose where to live.”

The thought stuck in her mind. For years, Jolly had reported on sexual violence against women and girls; just two years earlier, she’d covered a horrific gang rape and murder case in New Delhi, which had galvanized a movement against sexual violence in India and lit international headlines.

Now, she found herself reading up on violence against Indigenous women in Canada. She learned about British Columbia’s Highway of Tears, where more than 20 women have vanished or been slain during the past four decades. She convinced her BBC bosses to send her to Winnipeg to cover what happened to Tina.

At first, they were reluctant to send her here, so far away from the heartbeat of world news. But in November 2014, after another Indigenous teen was attacked near the river — and survived — Jolly was able to secure a travel budget and make her way to Winnipeg to report on these stories of pain.

That first visit would give way to four more, including a five-month stint in Winnipeg in early 2018. She visited Sagkeeng First Nation, where Tina grew up; she explored the North End’s streets. She built a close working relationship with Winnipeg police, who gave her an unprecedented look inside their investigation.

“‘Canadians? Racist?’ I’d always had the highest opinion of Canada… and also kind of looked at Canada as the kind of place you’d live if you could choose where to live.”

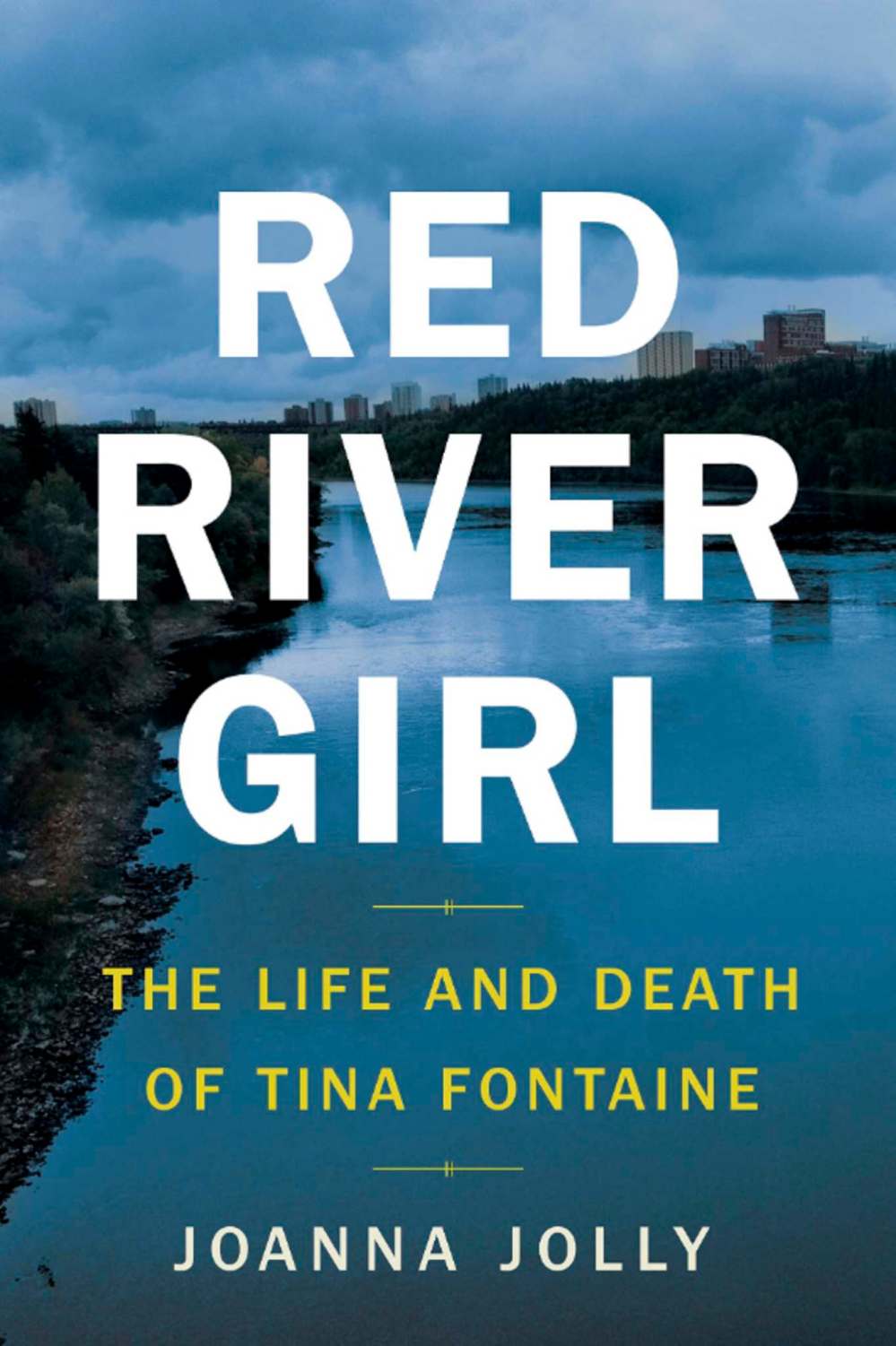

Five years and several articles later, the sum total of what Jolly found here is presented in her first book, Red River Girl: The Life and Death of Tina Fontaine. The book, which was released in Canada last week, offers a deep look inside the case, from the police investigation to the broader social context in which it occurred.

The truth is, Jolly came to love Winnipeg. She enjoyed the pace of life here, she says, the way rush hour seemed to slide by so quickly, the way Winnipeggers stretched out their lives on long summer days. But she was struck by the segregation of the place, the perceptions of the North End, the way non-residents spoke about it.

In Winnipeg, people asked her: aren’t there areas like that in London?

“Generally, I found that quite an alien idea in a modern city, to have this big area which is seen by many people as just unsafe,” Jolly says. “I spoke to many Winnipeggers who said, ‘Nope, won’t go near it.’ Or, ‘My husband won’t let me go near it, as a woman.’ I was learning a different side of Canada.”

In time, she came to have a unique view of the investigation, too. After Raymond Cormier was arrested and charged with Tina’s murder in December 2015, Winnipeg police approached Jolly, noting that it had been a remarkable effort; they offered to share the notes from their investigation.

That’s a highly unusual move for Winnipeg police; Jolly thinks that in a way, they wanted to work with an outsider, someone without the complicated relationship local media have with them. And as she learned more about the police work behind the arrest, she was struck by the breadth of the effort.

“There was an immense amount of manpower invested into it, and many, many people worked on it,” she says. “And they really thought outside the box about how they were going to conduct it. It’s clear they felt an enormous amount of pressure on this case, to get a conviction.”

Many results of that work came out at the trial: how police bugged Cormier’s apartment and scoured thousands of hours of audio for clues. How they tried to track down every one of the Costco quilts in which Tina had been wrapped. How they set up a Mr. Big sting to try to coax a confession out of the suspect, with little result.

“There was an immense amount of manpower invested into it, and many, many people worked on it. And they (the police) really thought outside the box about how they were going to conduct it. It’s clear they felt an enormous amount of pressure on this case, to get a conviction.”

In the end, the evidence that was presented at trial was insufficient to earn a conviction; there was little forensic evidence, not even a known cause of death. In February 2018, Cormier was acquitted.

Jolly was there when the verdict was read, and she witnessed the heartbreak that flowed from it. It was, she says, “one of the most emotional scenes” she’s ever reported. Outside, on the steps of the courthouse, she listened as leaders — including Sheila North Wilson, former grand chief of Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak — spoke about what it meant.

The journalist was struck by those words, by the show of leadership in the city. A colleague from Toronto called to report that out there, people were out on the streets in protest rallies; in Winnipeg, Jolly thought, the response felt more quiet, more focused on holding the memory and building the legacy of Tina’s life.

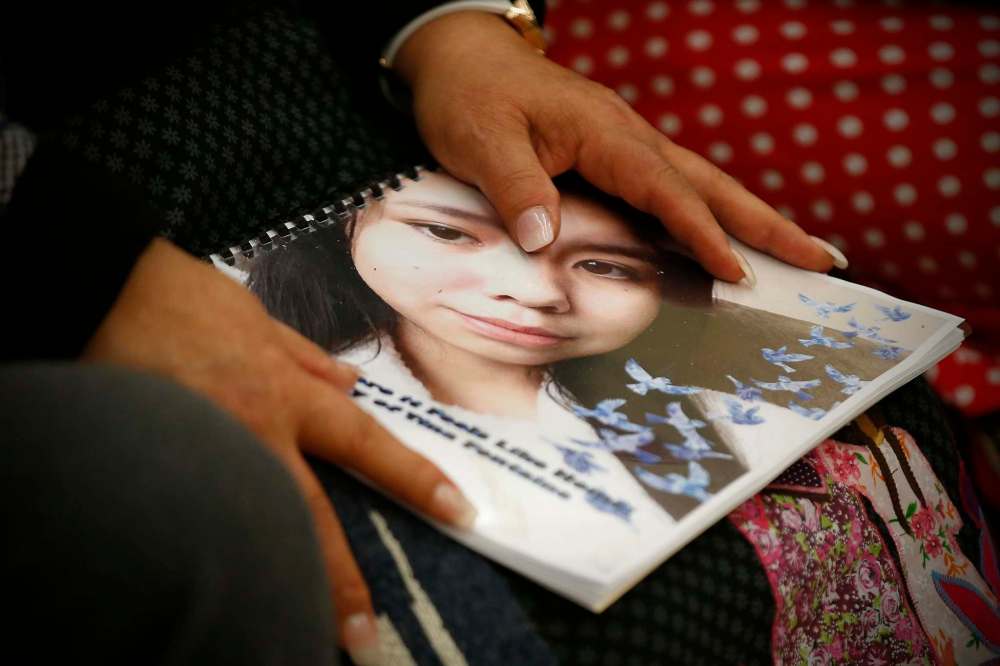

“It wasn’t the verdict that everyone wanted, but that doesn’t mean that Tina didn’t change everybody at the same time,” she says. “It’s difficult to know why she became the poster child. Why Tina, after so many victims? But she did, and her story touched so many people. Winnipeg was changed from that investigation.”

The book, she says, is not a political one. It wasn’t her intention to make a searing political statement — only to gather the facts about Tina’s death and subsequent investigation, and the larger social and cultural realities that shaped it. It’s for others to take that information and draw their judgments, make their conclusions.

And it is, above all else, a story about the life at the centre of the story, stolen from the heart of a city that offered no safe place for her. A young life that fell through cracks in the social fabric, cracks split so wide as to become chasms. The city too often prefers to forget about girls such as Tina; now, she will be remembered.

“I know a lot of true crime is about the crime itself and having a page-turning, thriller mystery,” Jolly says. “There’s an element of that in Red River Girl, but ultimately I wanted this to be a book about Tina… that she would be properly honoured.”

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Melissa Martin

Reporter-at-large

Melissa Martin reports and opines for the Winnipeg Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.