Little treasure on the Prairies Now a museum in the Dauphin area, the Negrych Homestead is a living snapshot in Manitoba history

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 19/10/2018 (2612 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The people who settled in Manitoba in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were tough, both physically and mentally. They had to be. They were driven by a desire to create a new life of freedom in Western Canada, and to make opportunities for their descendants.

Their homes provided few of the creature comforts that we take for granted today: primitive heating in winter using wood or coal, no cooling in summer, a toilet in a stinky and mosquito-filled outhouse in the yard, no hot and cold running water at the turn of a tap, no electrically-powered lights and appliances, no communication with the outside world at the lift of a handset, and certainly no big-screen television and internet access.

We assume that these wonderful conveniences came about gradually through the 20th century so, by the 1980s, most Manitobans lived a life of ease compared to their parents and grandparents. Therefore, it is curious to think that, as recently as 1990 in a relatively developed part of the province, some people eschewed a life of comfort to live essentially as their forebears had done.

This is the story of a remarkable site that is considered by heritage advocates to be the most complete and best-preserved pioneer homestead in Canada, and possibly all of North America. I am referring to the Negrych Homestead, located about 40 kilometres by road northwest of Dauphin or 20 kilometres northeast of Gilbert Plains. Operated today as a community museum, I tried several times over a period of years to visit it, always arriving when it was closed, until I finally managed to get there in the spring of 2017. I must say that it was one of the most moving experiences I have had during my decade on the road in search of historic places. Walking into the site seemed as though I had used a time-machine to jump back over a century, to see a log house almost exactly as it would have appeared when it was built in 1899.

In 1897, Wasyl (Basil or William in English) and Anna Negrych, accompanied by their seven children ranging in age from nine months to 19 years, left their home in the highlands of western Ukraine and boarded a sailing ship in the German port of Hamburg, bound for Quebec City. The trip was gruelling and at least two of the 788 passengers died in transit.

On arriving in Canada, the Negrychs travelled by train to Winnipeg then, after a brief stay, continued on to Dauphin, where 53-year-old Wasyl bought a quarter-section of land for $10. Thirty-three-year-old Anna and the younger children stayed in an immigration shed at Dauphin while Wasyl and the older children investigated their new homestead. Wasyl and his brothers Anton and Jan, and his cousin Iwan, had purchased the four quarter-sections of one square mile. Unlike settlers who typically built homes near the outer edge of their land, near a “road allowance,” the Negrychs built on the inner corners of their quarter-sections, along an old “colonization trail” that ran southeast-northwest through the property. The families created, in effect, a small Ukrainian village for themselves.

In conversation with Gordon Goldsborough

Gordon Goldsborough is an aquatic ecologist at the University of Manitoba. He is also the head researcher, webmaster, and a past president of the Manitoba Historical Society.

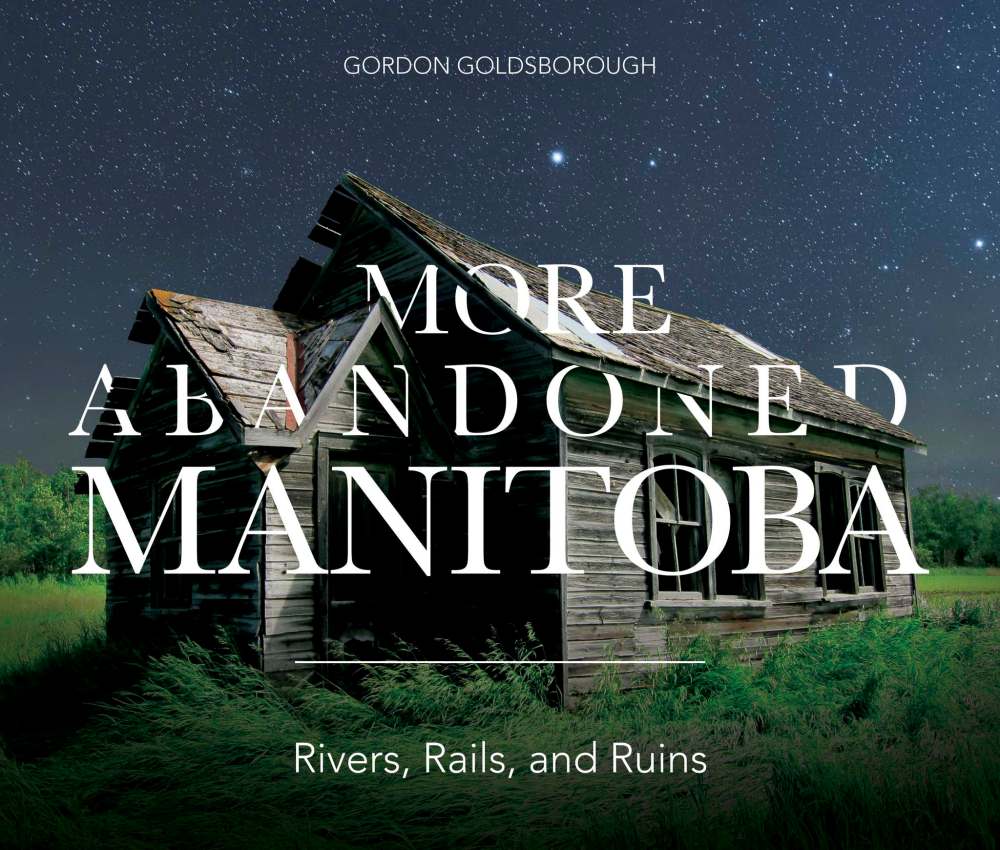

Most recently, Goldsborough has been documenting the history of derelict buildings all over Manitoba. He first began showcasing this research on the CBC’s Weekend Morning Show in 2015 with a column called Abandoned Manitoba and a bestselling book of the same name appeared in 2016.

Goldsborough will be launching the sequel, More Abandoned Manitoba on Oct. 25 at McNally’s.

Winnipeg Free Press: What do you want people to know about More Abandoned Manitoba: Rivers, Rails, and Ruins?

Gordon Goldsborough is an aquatic ecologist at the University of Manitoba. He is also the head researcher, webmaster, and a past president of the Manitoba Historical Society.

Most recently, Goldsborough has been documenting the history of derelict buildings all over Manitoba. He first began showcasing this research on the CBC’s Weekend Morning Show in 2015 with a column called Abandoned Manitoba and a bestselling book of the same name appeared in 2016.

Goldsborough will be launching the sequel, More Abandoned Manitoba on Oct. 25 at McNally’s.

Winnipeg Free Press: What do you want people to know about More Abandoned Manitoba: Rivers, Rails, and Ruins?

Gordon Goldsborough: My objective in writing this book was to make people curious about Manitoba and to encourage them to get out and see it for themselves. I like to think that my book tells stories about places in Manitoba that people have never heard of, about how our province has changed through the years, as revealed by abandoned places that I have visited in my travels.

WFP: For your two Abandoned Manitoba books, you’ve written about derelict schools, churches, stores, homes, grain elevators, and military bases. How do you find your sites?

GG: I have a wide range of sources. I find a lot of places that sound like they might be interesting through research at libraries and archives then I go out purposely to find them. Others are accidental finds that I stumble upon in the course of looking for something else entirely. Still others are recommended to me by people who know about my fascination with abandoned things.

WFP: You say that you enter these sites “armed with a drone and a deep curiosity about local history.” You’ve been documenting historic sites in Manitoba for decades — the Historic Sites of Manitoba map on the Manitoba Historical Society website comes to mind. At what point in your process did a drone become necessary? And do you use it for anything beyond taking aerial shots?

GG: The drone gives me an entirely different perspective on a historic site, especially when it is so large that what I see on the ground does not do it justice. For instance, a former Second World War training base east of Dauphin looked like not much more than a farm field with a few chunks of concrete here and there. From the air, however, the outlines of former hangars and other buildings, roads, and three large runways in a giant but overgrown triangle were clearly visible. The drone provides unique insight into the scope of historic places like this.

WFP: What has been your favourite abandoned building to date?

GG: There are so many favourites that it is hard to pick just one. My most recent favourite is a large building just outside of Churchill that was a military surveillance post during the Cold War. For just a few years in the 1950s and early 1960s, it was used to spy on Soviet communications to detect if a bomb-carrying plane was coming over the North Pole. The building has been abandoned for decades. I spent several hours exploring its many rooms and taking numerous photos. I looked closely at its unique architecture that allowed the building to remain level despite sitting on permafrost. (Ironically, the Soviets came to see it too, to learn about its innovative design.) I walked around in its former high-security area, whose windows are all boarded over, using the light of my mobile phone. There are lots and lots of other interesting places like this, but that one really stood out as a highlight.

WFP: What are the difficulties of doing local history research? Have you ever had a building you couldn’t find much about?

GG: This happens all the time. I find an interesting building (or some other structure) but am stymied at finding any information about it. Usually, local sources are the best ones but, sometimes, even the locals don’t know very much about a place, especially if it has been abandoned a long time. I find that posting a photo on social media can sometimes provide useful clues, and my best “go to” sources are books and documents at the Manitoba Legislative Library and the Archives of Manitoba, supplemented by historical newspapers. I’m confident that all these obscure places were reveal their secrets eventually. So I’m patient.

WFP: What do abandoned buildings say about our society? About what we value and what we leave behind?

GG: Abandonment is a statement of our priorities. A building that is abandoned is considered by its owner(s) not to be useful, and I am fascinated by the circumstances that led us to reach this conclusion. Over the last century, Manitoba has changed in so many profound ways, and I see signs of those changes in the abandoned places that I visit. We should be grateful for the ease and comfort of our modern lives, as compared to the ones lived by Manitobans a couple of generations ago, and abandoned places provide these reminders.

WFP: Which writers and historians were influential to you?

GG: I am inspired by writers whose work is informative and engaging at the same time. Two of the best writers of Canadian history, I think, were James Gray and Pierre Berton. Among professional historians in Manitoba, I love the work of Jack Bumsted, Jim Blanchard, Dale Barbour, and Nathan Hatton. They tell great stories in a way that is approachable by almost anyone. A few other writers/historians whose work I admire are Jake MacDonald, Charlotte Gray, and Margaret MacMillan.

WFP: What are you reading right now? What are you writing right now?

GG: I love to read but, unfortunately, I am so busy these days that I don’t have the luxury of much free time to indulge it.

My next book project is a history of the engineering and geological professions in Manitoba, to be published for the 100th anniversary of the Association of Professional Engineers of Manitoba (now Engineers Geoscientists Manitoba). It engages my technical background to a greater degree than my previous books and it is a great opportunity to write about what I really love: the history of things we take for granted in everyday life. There are many wonderful stories there waiting to be told.

Ariel Gordon is a Winnipeg writer.

Initially, the families built “buddas,” temporary A-frame structures made of locally sourced poplar poles covered in cowhides bought in Dauphin. In 1899, after his initial home was destroyed in a massive prairie fire that swept through the region, Wasyl Negrych built another one, in a style typical of ones in the Carpathian mountains of eastern Europe. It still stands today. The 15-foot by 35-foot structure is made almost entirely of wood with minimal metal hardware. Its walls are squared tamarack logs covered inside and outside, along with the interior ceiling, with homemade mud-plaster — made by mixing clay, straw, cow manure, and water — made strikingly white by adding laundry bluing to the wetmixture prior to application.

Unlike some such buildings, where the roof would be covered in thatching, the home’s roof was covered with wood shingles. Following a floorplan popular in their Ukrainian homeland, the Negrych home had three rooms, all with wooden floors. The main entrance led into a central room that served as a kitchen, with an iron cook-stove, shelves, and a washstand. Beneath the kitchen was a root cellar excavated into the ground for storing vegetables through the winter. A small room off one side of the kitchen was used as a pantry. The largest room to the other side was a combined bedroom and sitting room containing “two iron beds, a rocking chair, extension dining room table, a treadle sewing machine, a small box heater and a coal oil lamp.”

In their new home in Canada, the Negrychs had five more children, bringing their family to 12 children: six girls and six boys. They also built several other buildings on the site, including an earthen-floored bunkhouse (built in 1908 for the boys), cow barn, pigpen, chicken coop, three granaries (1898, 1908, 1940), and an icehouse, all made of logs. Inside the bunkhouse was a peech, a log-and-clay stove used for summer cooking. It also heated the bunkhouse in winter and provided smoke to cure meats in a lean-to beside the building. Surrounding the buildings was a vegetable, berry, and herb garden, an orchard (with plums, sour cherries, and six varieties of apples) enclosed with wooden rail fences, and small fields cut from the surrounding forest where the Negrychs grew grain and feed for their chickens, pigs, and cattle.

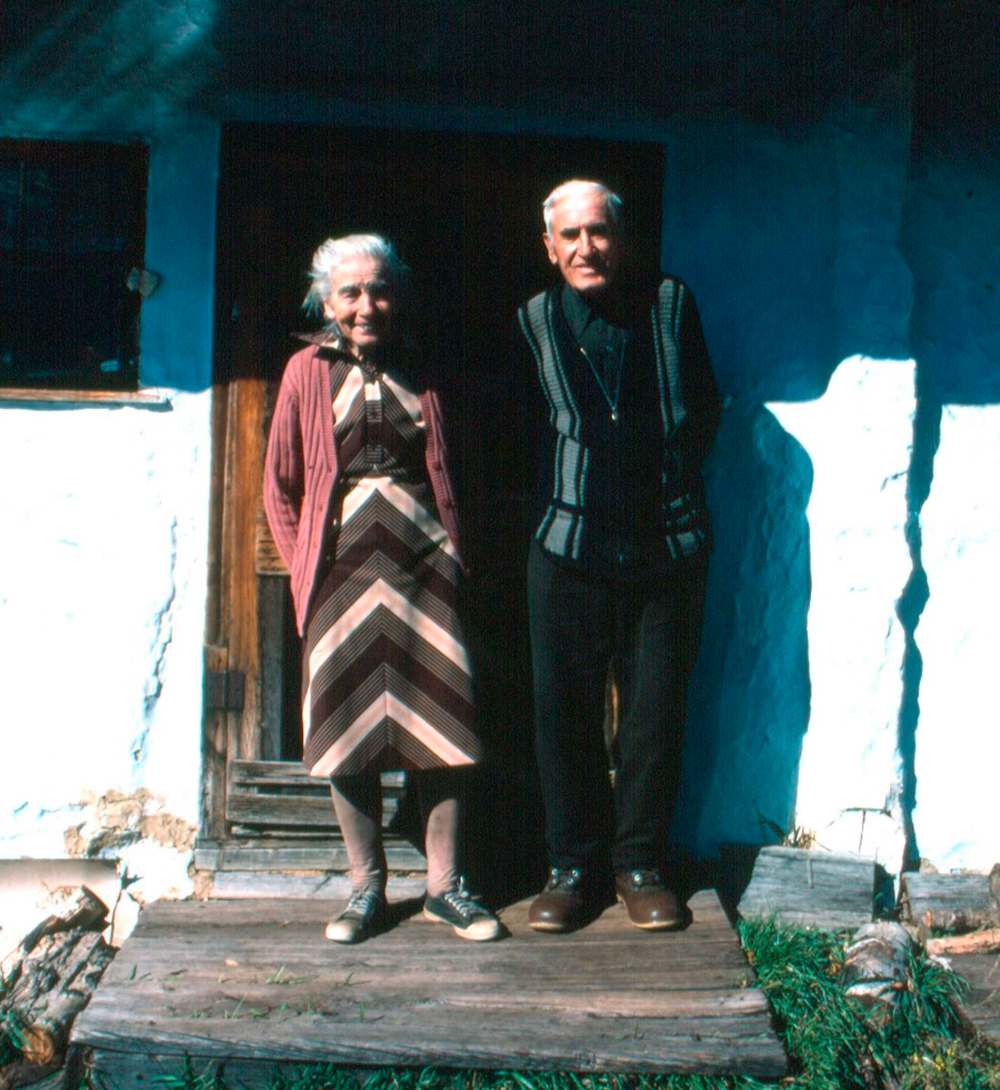

Wasyl Negrych died in February 1927, at the age of 83, and was buried in a little Ukrainian Orthodox cemetery a kilometre-and-a-half northwest of his home. Anna Negrych continued on until March 1944, when she joined her husband in the nearby cemetery. The youngest of their six daughters, Annie, born in 1907 and never married, continued to live in the original house into her 80s. Throughout her long life, Annie never had the house wired for electricity or a telephone. Lighting was provided by kerosene lamps, as they had years earlier, and heat was provided by a stove fuelled by wood. There was no running water. Instead, Annie would dip a bucket in the Drifting River that flowed about 30 metres away from her house. However, she did not lack for company. In 1968, her brother Stephen returned to the homestead to join her and their older brother Wasyl.

Born in 1903, Stephen Negrych had attended Wesley College in Winnipeg, then over the next 38 years until retirement, he was a teacher at a series of 10 one-room schools. Like he had done as a child, the old bachelor slept in a bunkhouse a few metres away from the main residence.

In 1983, Wasyl became ill and was moved to a personal-care home in Dauphin, where he died on Dec. 17, 1986. At that time, most of the farm machinery, animals, and building contents were sold at auction. With Bimbo, a small dog of indeterminate breeding, the two surviving Negrychs continued to live “off the grid” as their ancestors had done for generations, performing light chores during the day and reading in the evening by the light of a coal oil lamp. Occasionally, Stephen played his violin. Annie made meals on the old cookstove, fired by wood cut by Stephen in the surrounding forests.

Finally, in the spring of 1988, Annie Negrych moved into a seniors home in Gilbert Plains and she died there on Dec. 16, 1988. Stephen Negrych lived at the homestead until October 1990 when he moved into Dauphin. When he died at the Dauphin Hospital on June 23, 1992, he was the last of the pioneer Negrychs. He was buried in the same cemetery as his parents, along with Annie and many other members of his extended family.

The Negrych farm buildings, largely unaltered from their original appearance, survived far longer than most other pioneer farmsteads that were usually torn down when they were replaced by modern amenities.

Late in his life, Stephen Negrych is said to have hoped the homestead that his parents built would be preserved for its historical significance in commemoration of his parents’ pioneer spirit. In 1991, the local Lions Club began developing plans before he died. Initially, that would have entailed relocating the buildings to the Selo Ukraina Museum south of Dauphin, home of the National Ukrainian Festival. However, that would have destroyed the context for the buildings — the fact that each building sits in the same spot as when it was first built — which is their most unique feature. The move never happened and, instead, the Gilbert Plains and District Historical Society stepped forward with a commitment to protect and preserve the buildings where they stood. Consequently, the 120-year-old Negrych Homestead is the oldest-known Ukrainian-Canadian dwelling in Manitoba on its original site.

The Negrych Homestead began opening for public visits in 1994 and work continued through the 1990s with the refurbishing of old buildings and the construction of a few modern replacements, such as a piggery and an icehouse. Owned by the Municipality of Gilbert Plains, and leased to the Gilbert Plains and District Historical Society, it was designated as a provincial historic site in 1992, and as a national historic site in November 1996 (although the federal designation ceremony did not take place until August 2004). If you are interested in seeing this truly remarkable site, the Negrych Homestead is open daily in July and August, Tuesdays to Saturdays, from 10 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., or at other times by appointment. When you arrive at the site, be reminded that it is almost kilometre from the nearest public road along a twisting, tree-encroached driveway. There are no flush toilets and cellphone reception is spotty. But I can think of no better place to imagine you have been transported back a century and experience the fortitude with which hardy Ukrainian settlers set down roots in this region of Manitoba.