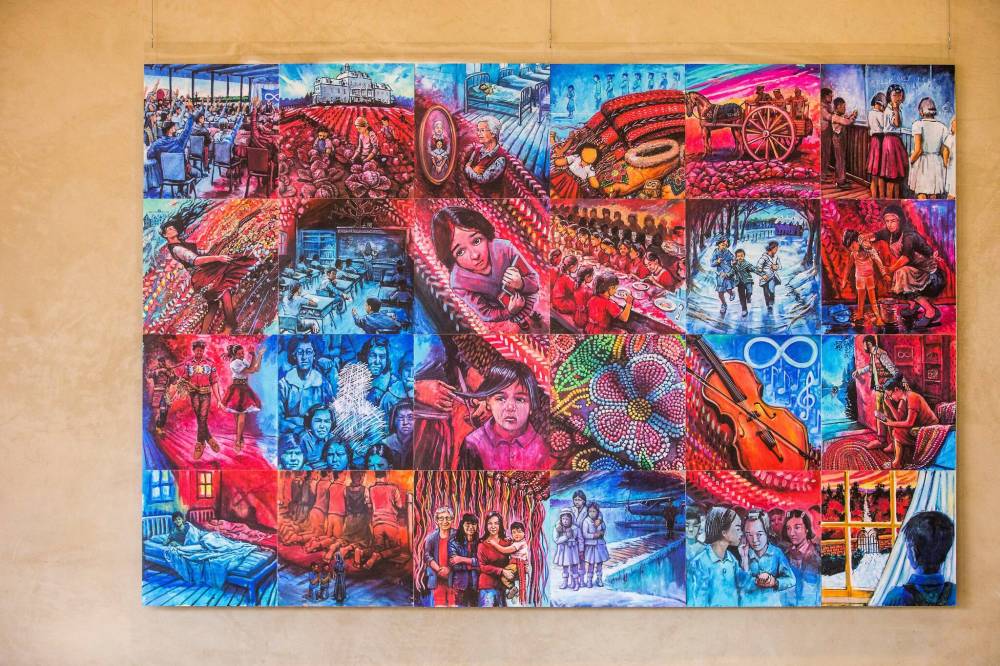

A mosaic of memories Vivid, visual vignettes convey Métis residential school experience

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 03/08/2022 (1223 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Tucked in a hallway corner at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, the new Métis Memories of Residential Schools exhibit demands that viewers do more than just watch passively — they must actively participate.

The 24-tile mosaic displays small blue and red vignettes of the Métis experience. Each individual tile is adorned with a teaching statement on the back. Viewers learn about Métis struggle, joy and survival — from flower beadwork to residential schools to cultural reclamation.

Yvonne Poitras Pratt and Billie-Jo Grant, the co-organizers of the project, are glad to host the exhibition in the homeland of the Métis Nation. The pair worked on numerous Métis educational initiatives together at the Rupertsland Institute in Alberta before embarking on the project together.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS

Organizers hope viewers will reflect on the Métis experience and then take action.

The project was birthed out of years of scholarship, conversations and storytelling from the Métis community. The Métis Memories of Residential School exhibit is an attempt to illustrate a host of experiences through bite-sized tiles.

“Every panel you see on there has been discussed by community,” Grant said. “This is a project that people will feel. Once they start feeling, we go from the mind to the heart, and they have a deeper understanding to move forward.”

One blue tile in the mosaic displays a group of Métis children with the middle child’s face scratched out in white ink. This particular tile is a testament to the fact that many Métis children in residential schools were replaced with a number or name that was easier for the school teacher to pronounce.

“What would it feel like to have someone replace your name with a name of their choice?” the tile asks the viewer.

Grant, who is the associate director of Métis education and K-12 initiatives at the Rupertsland Institute, said that Métis experiences are vastly underrepresented in Canadian school curricula. Installing the exhibit at a museum that thousands of students visit each year provides an opportunity to share authentic Métis narratives and histories with a wider audience.

Supplied photo

Métis Memories of Residential Schools co-organizer Billie-Jo Grant.

“We realize as Métis educators that the voice of Métis community is missing in resources, and teachers are really hungry for authentic resources,” Grant said.

Poitras Pratt, an associate professor at the University of Calgary, said Métis experiences in residential schools are often missing from the greater narrative of truth and reconciliation. The goal of the mosaic was to shed light on the various forms of colonial schooling. Not all Métis children were sent to residential schools; some were sent to industrial schools and day schools, where children received subpar education, Poitras Pratt said.

“The colonial landscape is far larger than just Indian Residential Schools,” Poitras Pratt said. “We (Métis) were involved not only in residential schools… we were also involved in industrial schools, and in day schools. Oftentimes our people, our children, were placed in public schooling systems where they were looked at as ‘halfbreeds’,” Poitras Pratt said.

For many Métis, including Poitras Pratt, the project’s narratives hit close to home. While curating the project, Poitras Pratt came across a photo of her mother at the Fishing Lake Colony School. While not a residential school, the Fishing Colony Lake School was imbued with a colonial legacy.

“She can tell us stories about what it was like to be taught by would-be educators who are actually religious leaders,” Poitras Pratt said. “There is the harm, whether you’re in a residential school or in an industrial day school, where you don’t have trained educators.”

Supplied photo

Métis Memories of Residential Schools co-organizer Yvonne Poitras Pratt.

With the exception of the painter Lewis Lavoie, Grant said everyone on the Métis Memories team is Métis. The project would not be possible without the guidance of Elder Angie Crerar from Grand Prairie and the Métis community members who graciously shared their thoughts and stories.

Lavoie’s job was to translate original Métis stories into visual imagery — a job Grant said was done exceptionally well.

“He did so much listening and was so humbled by it,” Grant said. “That type of teaching we’ve actually taken into university classes to share.”

Sometimes, listening meant repainting sections of the tiles multiple times to get the story across in the right way. Sometimes it meant tweaking a facial expression or changing a dress colour. The overarching goal was to reflect each experience as authentically as possible.

In a way, that’s what viewers of the Métis Memories exhibit are obliged to do as well. The mosaic is not a stagnant artwork, but rather a conversation. It’s a call to reflect and to take action.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS

The tiles were painted by Lewis Lavoie, whose task was to translate original Métis stories into visual imagery. This sometimes required repainting sections of the tiles multiple times.

“People don’t know these stories, and so that’s what we’re here to do, it’s to share those stories,” Poitras Pratt said. “We are working extremely hard to get our stories out there in an authentic way, and now we need Canadians to not only wake up, but to take action.”

The Métis Memories of Residential Schools exhibit can be viewed at no cost at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights Community Corridor from now until Jan. 13, 2023.

cierra.bettens@freepress.mb.ca

Supplied photo

Elder Angie Crerar from Grand Prairie and the Métis community shared their thoughts and stories for the project.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS

The Métis Memories of Residential Schools exhibit at the CMHR is made up of a number of blue and red tiles, with teaching statements on the back of each tile.