What if? The day Nazis ruled Winnipeg A colossal war-effort fundraising campaign 80 years ago designed to give residents a taste of life under the Third Reich offers contrast to issues dividing Canadians today

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 18/02/2022 (1390 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Dora Paul was 14 years old when she saw her first Nazi.

She left her house on Lisgar Avenue on Feb. 19, 1942, and walked to a lunch counter run by the mother of her friend Shulames Kirk. Mrs. Kirk’s was a busy restaurant on one of the busier streets in town, the main thoroughfare of Jewish life, the Portage Avenue of Winnipeg’s North End: Selkirk Avenue.

The Yiddish language flowed freely, as did Ukrainian and Polish. It was as if life in Eastern Europe had been preserved and carried across the Atlantic to be placed in the geographical heart of North America. On Selkirk Avenue, shtetl and city merged into one.

Dora and Shulames had met at the Sholem Aleichem, a left-leaning Jewish school that stressed socialism and the ideas of class struggle. When she was 14, Dora went to Aberdeen School, where the majority of the students were Jewish like her. They were as politically aware as 14-year-olds could be, but still, they were 14; the world was so big and they were so small. There was much happening that they could not have possibly understood.

The war was far away, but it was not an abstract concept to Dora: her brother, Lavey, was engaged in tank warfare in Italy, and she and her classmates, along with every person still in Canada, had been conscripted to fight as well, albeit in a much different manner.

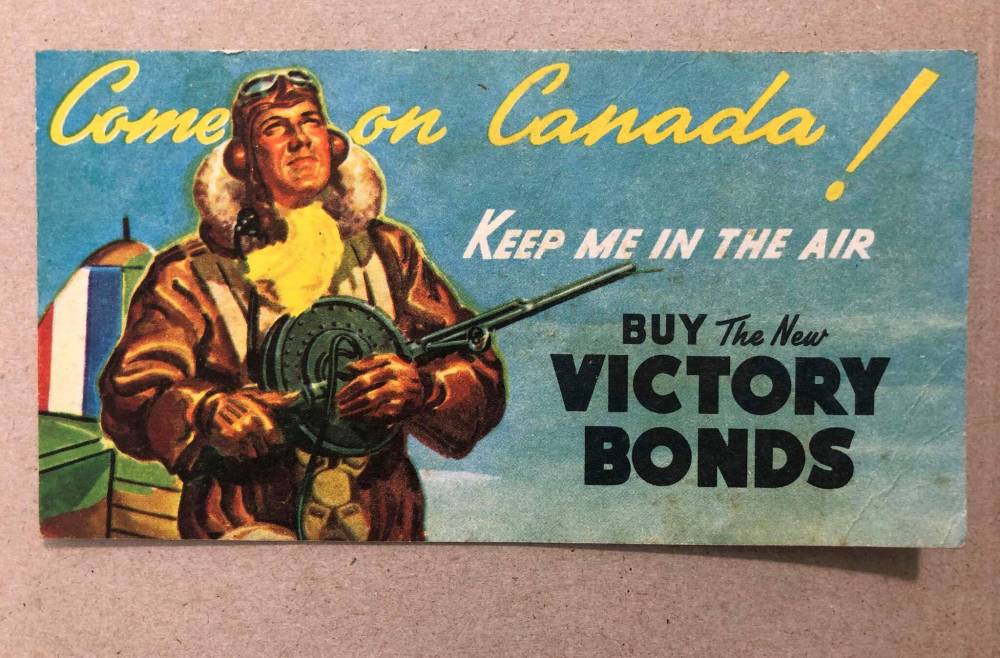

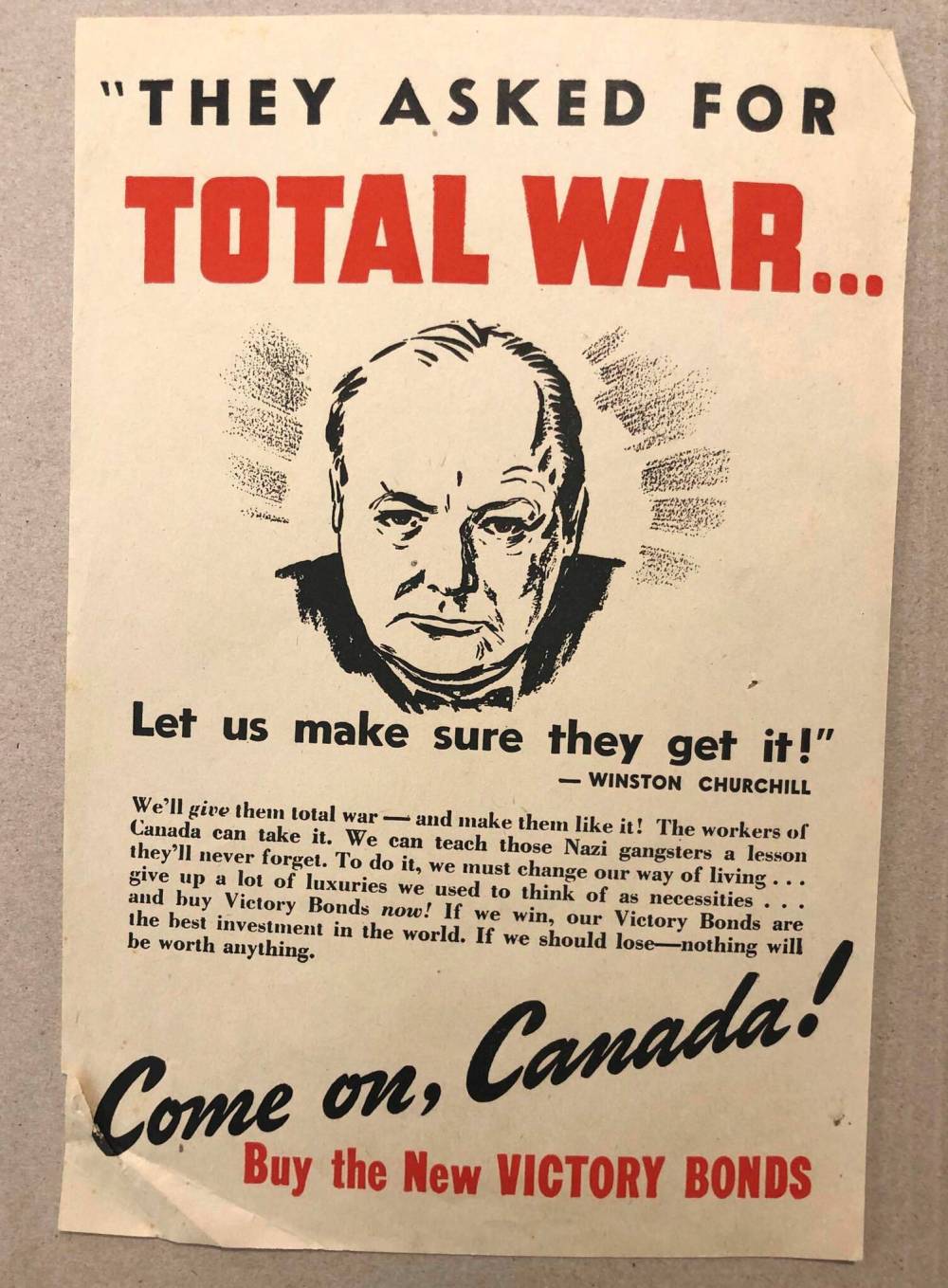

The Department of War Services ran extensive campaigns to encourage support for the war effort against the Axis, asking Canadians to give money and save paper, discarded scrap metal, grease and aluminum foil to be used in the manufacture of war materials.

“Don’t Throw It Away,” the ads read. “Throw it at Hitler.” Winnipeg’s Canada Bread Company began selling “Victory Loaf.” The war effort had invaded the classroom, the press, the grocery store.

But it was February 1942, and Europe was a world away to Dora. At that point, there were rumblings of the evils occurring overseas under the Nazi regime — the systematic mass murder, the destruction, the antisemitism, the racism, the homophobia, the eugenics, the assault on human liberty for the sake of an idea of Aryan supremacy — but information back then came in trickles, not streams.

“Holocaust” was a word not yet in use. Polish jurist Raphael Lemkin had yet to coin the term “genocide.” The war was a world war, but it was not yet clear to those not witnessing it first-hand just how drastically it would alter the world they lived in.

The National War Finance Committee and the Manitoba War Savings Certificate Program sought to show people just that, with a flair for the dramatic, in an attempt to convince Canadians to reach into their wallets and look into their hearts.

A year earlier, on Feb. 7, 1941, the certificate program decided to put on a performance to kick off its fundraising drive: the Battle of Portage and Main.

At 11:45 a.m., alarms began sounding, alerting the city to approaching enemy aircraft. City police showed up to keep the peace and control the public. Streetcars screeched to a halt. Thousands of workers rushed out of their offices and headed to the iconic corner, where khaki-clad soldiers of the 13th Field Regiment and soldiers of the artillery training centre took their battle stance.

The RCAF band played on, and motorcycles revved their engines: the enemy had arrived with its big guns. Officers barked commands, and the good guys crouched behind their anti-tank rifles. Over a loudspeaker, an omniscient voice narrated.

“Suddenly, a clapper could be heard… Gas!” the Free Press reported. “The men in the street became ghouls — strange, fierce-looking men of another world — as they put their masks on.”

The crowd fell hushed. The artificial war game for a moment felt real, and the silence was broken by five silver streaks in the sky: the air force swooped in, and half an hour after the battle began, the soldiers packed up their arms, and paraded down Main Street to Selkirk Avenue, across the Salter Street Bridge, and back to their barracks via Portage Avenue.

“Thank heavens, this is only fun,” someone in the crowd said, according to the Free Press report.

But the games were far from over. The Battle of Portage and Main proved effective at capturing the public imagination and, paired with ongoing publicity in the press surrounding the war effort, was an impactful form of state propaganda. While in good fun, the fracas brought the battle home. Next, to bring home the war.

By the following February, the conditions in Europe had become more desperate, with Germany continuing its march across the continent. Anxiety was high, and in Canada, thousands of families were left wondering whether they’d see their fighting relatives return home alive and well.

Support for the war effort was relatively strong, but could be stronger, and the National War Finance Committee’s Manitoba arm was seeking a way to publicize its second instalment of the Victory Loan campaign. The local chapter had set its sights on raising $45 million.

How to do it? How to inspire fear and incite generosity? How to show — not tell — what was happening in Europe under the leather gauntlet of the Nazis? How to bring over there, over here?

Other cities hosted mass bonfires to stoke support for the upcoming campaign. But that would not work in a Manitoba winter. They needed to do something on a grander scale that could not be ignored. They needed to craft a public relations stunt that would show Canadians why it was so important to lend as much money and time as they could to the war effort. They needed to show what was at stake.

What if, for one day, the Nazis invaded Manitoba?

● ● ●

The Nazi airplanes first flew over Norway House.

They weren’t really Nazi aircraft; they were property of the Royal Canadian Air Force, under the command of Col. D.S. McKay. It was before midnight, and the aerial activity signalled the beginning of the largest military operation in modern Manitoba history.

While the invasion itself was all false, its impact was entirely reliant on the commitment to the bit: the surreality of the day was underscored by an extraordinary level of co-operation from the military, the professional class, the working class and the political elite.

The military assembled at the Fort Osborne Barracks and the armouries at Minto and McGregor, with every local reserve unit participating. When air-raid sirens sounded at 6 a.m. that Thursday of what would be known as If Day, the local troops established a defensive perimeter surrounding Winnipeg’s city hall, having already learned of the fall of Selkirk.

Troops from the Fifth Field Regiment, the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders, the Royal Winnipeg Rifles and the Winnipeg Grenadiers, among other units, formed the defensive corps, while organizations such as St. John Ambulance and the Manitoba Volunteer Reserve gave their time to play along in the ensuing invasion, Winnipeg historian Jody Perrun recalls in his book, The Patriotic Consensus: Unity, Morale and the Second World War in Winnipeg.

The battle began in East Kildonan, with blank artillery firing away. The gunfire of Nazi panzer forces rattled back. The Nazis meant to dominate, and by 9:30 a.m., had overwhelmed the defenders of the city, who waved a white flag and saw the Union Jack at city hall replaced by the red, white and black of the Nazis. The swastika climbed up the flagpole and waved freely in the wind.

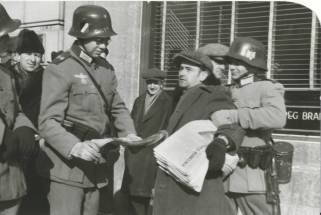

These men were not Nazis, but played the part convincingly. Members of the Young Men’s Section of the Manitoba Board of Trade, they marched throughout the city with the air of superiority, sneering and leering at those who passed them on the street as they went about their military operation.

One hustled past Dora Paul on the Salter Bridge, his helmet emblazoned with a swastika. The smoke from a false bomb burned her throat.

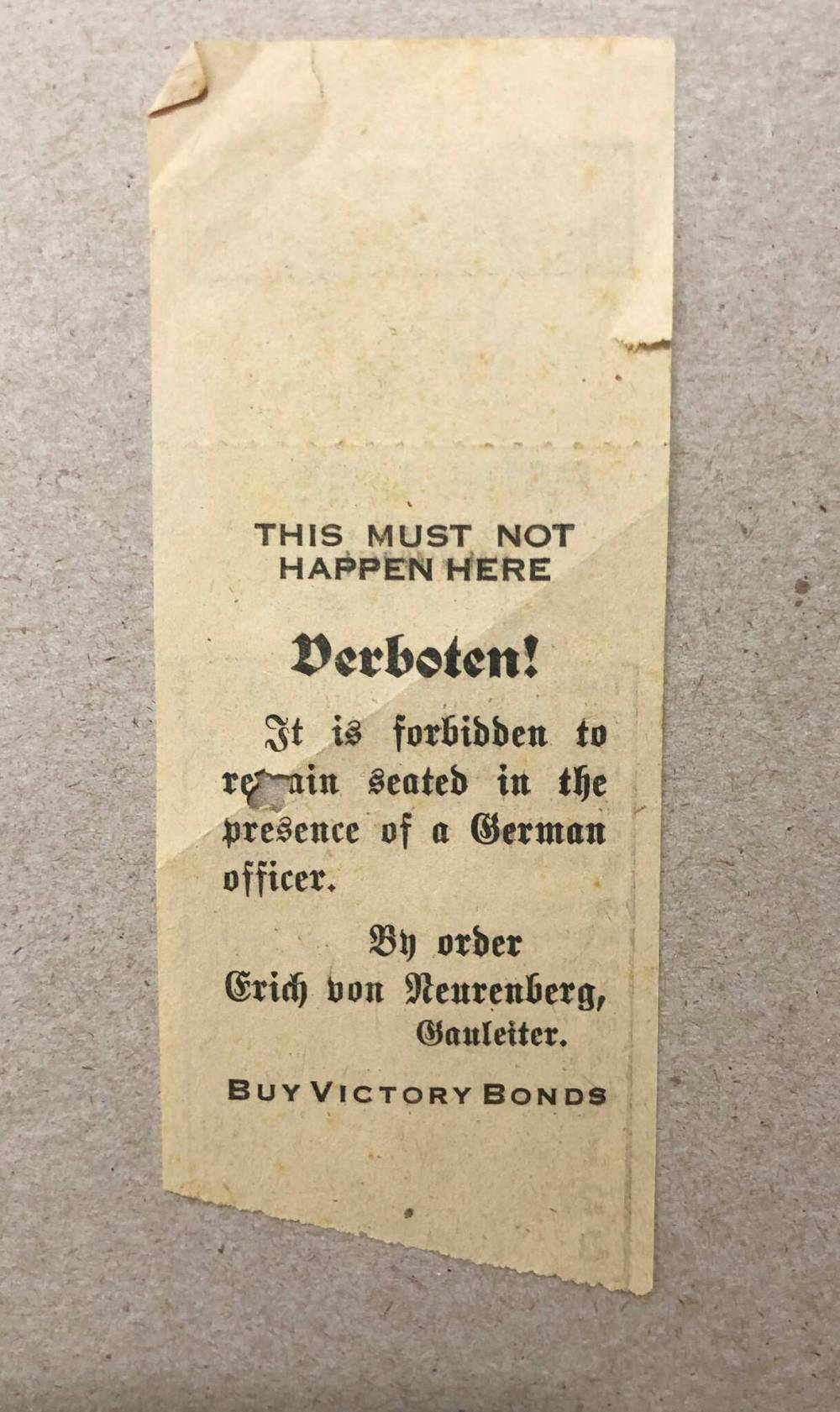

The invasion was swift: Brandon and Flin Flon fell, and Virden became Virdenburg. In a matter of hours, Winnipeg would become Himmlerstadt, Portage Avenue was redubbed Adolphe Hitler Strasse, and carrying rifles and guns — unloaded — on loan from the military and local gun clubs, the fake Nazis ran amok, beginning to inflict their new will. Posters were plastered across city walls, proclaiming the new rules by which the citizens of Manitoba would be governed.

“Ankundigung” — “announcement” — “This territory is now a part of the Greater Reich and under the jurisdiction of Col. Erich Von Neuremburg, Gauleiter of the Fuehrer.”

The new laws were meant to evoke life under Nazi rule: “all national emblems excluding the Swastika must be immediately destroyed,” one read. “No one will act, speak, or think contrary to our decrees.”

A newsreel camera crew from the Associated Screen News, led by a man named Lucien Roy, captured the production in stark detail. The young men played their roles, operating out of a building on Princess Street. The troops entered and seized the Legislative Building, standing on the steps like a family posing for a portrait.

The Winnipeg Public Library, then on William Avenue, was raided, with books thrown into piles and set afire. Rev. John Anderson of the All Saints Anglican Church was ushered away from his pulpit and arrested. Looting erupted on Broadway, and stormtroopers made off with furniture and household goods.

Premier John Bracken was ousted from his office and imprisoned at Lower Fort Garry, as was Wilhelm de Morgensterne, the Norwegian minister to the U.S., whose visit to Lt.-Gov. R.F. McWilliams coincided with the false invasion.

At the Great-West Life Assurance Building, employees were harassed and heckled as they ate their sandwiches and drank their coffee in the cafeteria. They were inexplicably pulled from their tables and jailed.

“Barking” in German, the dayplayers searched for the police chief, who took a well-timed lunch break and evaded capture. At city hall, mayor John Queen, along with several city staff, was arrested; alderman Dan McClean hid in an empty committee room. “The jack-booted Nazis failed to find him,” wrote Rick Groom for a Free Press article in 1985.

By nightfall, McClean was in handcuffs. Hitler’s speeches and martial music were broadcast on the radio, reichmarks replaced Canadian currency, bus transfers were written in German and passengers en route to Charleswood were arrested mid-commute.

At Robert H. Smith School in River Heights, the principal was arrested, and with a touch too-on-the-nose for Hollywood, a lesson plan on democracy at a Catholic school, written in chalk on the blackboard, was wiped clean by the bare hand of a Nazi commandant. Only “the Nazi truth” would be taught there henceforth.

One man, interviewed in a 2006 documentary by Aaron Floresco and historian Rhonda Hinther, recalled the thrill and fun in playing make-believe.

Watching the newsreels, which are easily accessed on YouTube, or Hinther and Floresco’s documentary with the volume muted, an observer could be forgiven for mistaking Winnipeg for Warsaw in 1939.

“Most remarkable is the true-to-life behavior of the principals concerned, the Nazi soldiers and the crowds in the streets,” the Winnipeg Tribune reported of the newsreels, which were seen by an estimated 40 million theatregoers in North America.

“Entering fully into the spirit of the event, all acted with such sincerity that those not knowing it was only make-believe might easily take the incidents for the real thing.”

What was missing were casualties — the only If Day injuries were a sprained ankle and a woman who cut her finger while making toast with her power blacked out. What also was missing from the attempt at realism was a core piece of the reality: the Nazis’ rampant ideologies of targeted hate and racial supremacy.

While hyper-realistic in many regards, the hypothetical invasion unfurled in a drastically different manner than what was happening in towns across Europe.

The troops stormed Robert H. Smith and the All-Saints church, yet according to reports of the day, places such as the Sholem Aleichem school, the House of Ashkenazi Synagogue and the city’s foremost Black church, Pilgrim Baptist, were left alone.

But that did not mean those in those places did not see what happened on that cold February day.

•••

The event was heavily publicized in the English-language press, though hardly so in the mainstream Jewish press.

In the days leading up to If Day, the Tribune and the Free Press, plus smaller publications in towns such as Baldur and Morris, ran advance warnings. Meanwhile, the Jewish Post, headquartered on Selkirk Avenue, ran wire reports of mass executions of European Jews, Roma and political dissidents a continent away.

“The roads leading to the concentration camps of Brest Litovsk, Bialystock and Lublin are choked with the bodies of murdered Jewish war prisoners machine-gunned by their Nazi guards,” an item on the front page of the Feb. 5 edition of the Post read.

Nobody expected, nor should have expected, the simulated invasion to be completely realistic; it was never planned to lead to actual calamity, and some details were obviously too grim to feature in the planning.

The goal was to strike fear into the hearts of Manitobans about what would happen if the Nazis made their way to Portage and Main. What the organizing committees did was enough to accomplish that goal.

But consider for a moment a different, more realistic hypothetical than a Nazi invasion: that some people did not get the memo. One Albertan unsuspectingly drove his car into Winnipeg only to see stormtroopers surrounding the Bay or Eaton’s.

“According to witnesses,” Rick Groom wrote in 1985, “the Albertan abruptly did a U-turn, slammed on his brakes and got out of his car.”

Now, consider those who did not listen to the English radio or read English papers. The Ukrainians, Jews, Austrian, Poles and Czechs who still lived in clusters in some ways more akin to the old country than the Chicago of the North. The Yiddish speakers who read the paper in their “mamaloshen,” their mother tongue, and not the official language. Racialized people who called the province home. Groups who already knew with varying levels of acuity what a Nazi invasion truly meant for people like them.

Dora Paul, who later became Dora Rosenbaum, recalled that in the fall of 1941, a pair of round-faced brothers who spoke only Polish and Yiddish joined her class at Aberdeen School abruptly, midway through the semester. They were brilliant in math and science, regardless of their linguistic limitations. These Jewish boys had managed to escape Europe alive, and they may have been somewhere in Winnipeg when the fake Nazi tanks rolled through town.

The premise of If Day as a fundraiser for the masses proved hugely successful; the goals for the war effort were exceeded in a matter of days. But for as much as it aimed at realism, the organizing committees ignored reality and lived experience.

They asked what would happen if the Nazis arrived, and if their ideology permeated a civilized country such as Canada, a province such as Manitoba or a city such as Winnipeg.

They neglected to acknowledge that the ideology, and those most at risk from it, had already been here.

•••

Maurice Steele was born in 1929 in Rovno, a city in Poland where the majority of the population was Jewish. He grew up in nearby Zornov, a small village, where they were the only Jewish family in town. His father worked in the lumber business and his uncle ran an oil-seed crushing plant. In earlier business ventures, members of his family ran the town tavern and the local flour mill.

Once or twice a week, Steele would walk 3.5 kilometres to what is now called Varkovychi, where they attended a Jewish school. In Zornov, he did not experience antisemitism directly. “But there was antisemitism there,” he says. As a child, he did not see what was coming.

But his mother Manya did. She was friendly with the local elite, who asked her a very pointed question: “What will you do when the Germans come?”

Steele’s father Shloeme was hesitant to leave, but his mother caught her friends’ drift. “She had a general feeling this wasn’t the place for children to be growing up.”

Shloeme Steele applied to work for the Canadian Pacific Railway, which was looking for two things: to fill its transportation network and to find farmers to purchase their land in Western Canada. In 1935, local law in Poland shifted, and Jewish people were allowed to be landowners, Steele recalls, and his father owned a parcel so narrow “he couldn’t turn the wagon around on it.”

“By that virtue, we were farmers,” he said. And by May 1939, he, his sister Mira, and his parents were bound for Winnipeg.

“If we had known what was going to happen we could have taken more of mother’s siblings, but who knew what was on the horizon at that time?” Steele said. Had they stayed much longer, there is little doubt what their fate would have been; many of his relatives died in the Varcovyci ghetto.

His uncle Morris was, at a certain point, the only Jewish person left. His wife and daughter were killed, and for two years, he lived under the floorboards of a horse barn owned by a Ukrainian friend before spending two more years embedded with partisan forces.

(When Steele returned to Rovno in 2005, there were six or seven Jews left, he said. On Nov. 6, 1941, the 17,500 adult Jewish inhabitants, and more than 6,000 children of Rovno’s ghetto were executed in the pine forest outside the city. By July 1942, the Germans declared that Rovno had been “cleansed of Jews.”)

When Steele arrived in Winnipeg, his family lived on the second floor of a farm in Old Kildonan, where a German farmer also lived with his family on the main floor. They had about 1,000 chicks on the third floor. One night in May, the farmer and his son invited Steele to go into the city for the evening.

The two young boys played on the balcony of the Winnipeg Auditorium, now the home of the Manitoba Archives, for what turned out to be a meeting of the Deutscher Bund, a fraternal organization founded in the 1930s, which had many members allegiant to the Nazi cause.

In January 1939, the Tribune reported that local Germans were under tremendous pressure to conform to pro-Nazi ideals in the leadup to war. “They admit that a considerable measure of success has been achieved in making converts to Naziism among people of German stock in Manitoba, especially among those under 30 years of age.”

More than 5,000 people were in attendance at a Bund-organized event in River Park, where Bernhard Bott, the leader of the western chapter of the Bund — a “vociferous proponent of Nazi philosophy” according to former University of Winnipeg scholar Jonathan Wagner — insisted on giving the Nazi salute.

Long before the concept of If Day percolated, the Bund had already committed itself to spreading propaganda of its own, albeit of a much more insidious, supremacist brand.

Their national publication, The Deutsche Zeitung fur Kanada, began publishing in Winnipeg in 1935. “Week after week, the Zeitung has hammered away with propaganda derogatory to the Jews, whom it blames for many of the world’s problems,” the Tribune reported.

The Zeitung, the Bund and Bott freely expressed their hate-filled views in the months leading up to the war, at which point, publication ceased.

Meanwhile, Wagner noted in a 1978 interview, there were active local fascist chapters comprised of both British and French Manitobans. The same week as the Tribune article on the local contingent of Nazism, Free Press writer Francis Stevens visited the Bund’s clubhouse on William Avenue.

“In view of the fact that the members are all Canadian citizens it is worth noting the decorative features of the main room include two Nazi flags with red fields, white circles and black swastikas, and a picture of Adolf Hitler looking fierce and mystical all at once,” Stevens wrote in his piece, which failed to mention any sort of racism or hate inherent to the policies those symbols represented. “On the opposite wall is one Union Jack and a picture of His Majesty King George VI.”

The auditorium where Steele found himself was decorated similarly with a packed crowd. “There were swastika flags,” he remembered. “And of course I had no idea what the proceedings were all about. But when I described it to my folks, they told me it was a Bund meeting.”

Those types of meetings soon went underground when the war was declared, but Steele was never allowed into the city with that German family again.

(After the war, Steele’s family reconnected with and brought his uncles Morris and Abe, along with Morris’ newborn son, Sam, and Morris’s wife Sonia, to Winnipeg. Incidentally, Sonia’s sister Clara met a widowed man from Poland in the postwar years, and married him, moving to Ecuador where the man’s first wife, Esther, who did not survive the Holocaust, had relatives. The man Clara married was my great-grandfather Saul Leszcz, and in the early 1950s, he came to Winnipeg, with his wife Clara, his son, Hymie — my grandfather — and a newborn daughter named Eva, with their son Molyn being born soon after they arrived here.)

When If Day happened, Steele and his family were living on a farm in Stony Mountain, but they and other families like theirs living in Winnipeg had already understood the threat that unchecked Nazism and fascism posed.

The hypothetical was very real.

•••

Brandon University history professor Rhonda Hinther was studying toward her PhD at McMaster University in Hamilton in the early 2000s when her Alberta-born officemate told her about If Day for the first time.

As a summer job, he once worked on a “This Day in History” calendar, and the entry for Feb. 19 was about the staged invasion. It happened in your home province, said the officemate, now a history prof at Laurentian University. He figured she, of all people, had heard of it.

Hinther hadn’t, and she filed that factoid in the back of her mind. When she met her partner Aaron Floresco, a filmmaker, she mentioned it to him, and the two saw a documentary in their minds. Here was a largely forgotten and unexplored slice of Winnipeg history. It appealed because of its subject matter, which was campy and kitschy and offbeat.

“It was such a weird idea for a publicity stunt or fundraiser,” she said. “Let’s get people to dress up as German soldiers.”

The fake invasion sounded too fake to have really occurred. “As far as a story for a film, it felt like a gift,” she said.

She dove into the archives, and the pair tried their hand at finding some living participants. They put calls out, finding only a few who were still alive to recall the operation. The 21-minute documentary, available from the Winnipeg Public Library, effectively brings to life the news reports of the day, and puts into perspective the co-ordination required to pull it off.

To Hinther, If Day was a success from a financial point of view. Winnipeg easily surpassed its quota of $23.6 million, as did Manitoba with its $45-million target, she said. That’s due in no small part to the theatrics of the staged invasion.

It was also “tremendously” effective in driving home the severity of a potential invasion, plus how an occupation would affect the common Manitoban. An enormous map, divided into 45 sections, was placed on the Bank of Montreal building at the corner of Portage and Main. For each million dollars raised, a Union Jack was placed on the map. It was filled with red, blue and white.

But as an experiment in reality, it had its shortcomings. The entire day was centred on a hypothesis of the hate and inequity that would inevitably arrive if the country were invaded.

Meanwhile, there were clear and overt examples of different types of hate and discrimination occurring on Canadian soil. The residential school system was operating in full force, in what is now widely considered an act of genocide, and the ongoing struggles of Indigenous people against colonialism were, and still are, vast.

During the war, some labour activists and political dissidents were interned in Manitoba. Japanese Canadians had their land seized with the onset of war and were considered enemies of the state facing internment.

Many people from specific ethnic groups and races were either barred from educational institutions or were up against steep and restrictive quotas in their attempts to attain an advanced education. There were several groups of people living in Canada who did not have the right to vote. The list goes on.

“I think If Day speaks to the inherent contradictions in the ways democracies function and how these can be amplified in times of war,” says Hinther. “It glossed over and obscured difference, as well as longstanding patterns of discrimination and (inequal) civil liberties.”

This often happens during times of adversity, when messages of unity are preached. Even when sharing the same battlefield, certain people always have more to lose and tend to lose it faster.

•••

Eighty years after If Day, there appear to be people who require a reminder of what true loss of freedom and fascism are.

On the grounds of the Legislative Building Tuesday afternoon, a sign rested in the snow on the median on Broadway falsely and insidiously comparing the provision of free, life-saving vaccination to the criminal and unethical experimentation by Nazi doctors in concentration camps.

Another woman, the day before, walked down the street carrying a sign reading “Nuremberg 1947.” There have been more than a few Confederate flags flown. Each is a symbol of hate.

While If Day was a single day of revisionist history, an experiment in hypotheticals, the above instances are the result of one of two things, or both: a willingness to forget, or the ignorance to have ever learned what truly happened during the course of history. Both are dangerous, both are irresponsible and both present an opportunity for introspection and interrogation.

Although the invasion of Winnipeg never manifested, and Winnipeg remained untouched by foreign troops during the Second World War, certain elements that played out on the city’s streets on Feb. 19, 1942 are happening before our eyes: a denial of history; a denial of fact; and the pervasive, pernicious power of propaganda.

There is no credible comparison to be made between the battle playing out today over freedoms and the one that Manitobans were forced to imagine when considering the invasion of the city by Nazi forces in 1942.

To compare the pain of potential genocide and military occupation to the challenges of a pandemic would be a disservice to history and does no one any favours.

The one place where the two battles share common elements is that they both rely on dishonesty and misinformation, with one key difference. The organizers of the battle that happened 80 years ago told the public it was all a lie. Many participating in the one happening downtown today claim that their misinformation is the truth.

ben.waldman@winnipegfreepress.mb.ca

Ben Waldman covers a little bit of everything for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Saturday, February 19, 2022 10:00 AM CST: Corrects spelling of Lavey

Updated on Saturday, February 19, 2022 12:36 PM CST: Fixes typo

Updated on Saturday, February 19, 2022 12:46 PM CST: Fixes typo