Doing time with John Paizs The 1985 film Crime Wave was Winnipeg auteur’s big break — after the first screening almost broke him

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 22/12/2022 (1176 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

John Paizs thought his career was over.

It was 1985, and Paizs was waiting in the old Winnipeg airport with precious cargo sitting in his lap at his gate: the canisters containing his first-ever feature film, a picture he directed, wrote, produced and co-starred in. It was called Crime Wave, and it was his carry-on luggage for a flight to Toronto.

The trip was potentially career-making, with Crime Wave set to screen at that year’s Festival of Festivals, an annual competition that soon became known as the Toronto International Film Festival.

Paizs, then 27, was a nervous wreck.

“It wasn’t until I was sitting at the airport that I crashed,” he says. Mentally, he was exhausted, having put two years of his life into his feature film. “It hit me. It’s finished. There’s nothing left to do. It was the moment of truth: How would this go?”

Since his early teenage years, when he first picked up a camera and made a movie, thus making him, by definition, a ‘filmmaker,’ Paizs had been obsessive as both a creator and recipient of visual art: Crime Wave — a movie ostensibly about writer’s block, now considered by many to be a cult classic, and an elegantly constructed experiment in visual storytelling — was the end result of those transactions.

On the plane, Paizs tried to reassure himself that the screening would go well.

In the near future, some of the most influential figures in Canadian cinema — including directors, producers, distributors and film critics — might see the stories the canisters contained. What fun.

An inauspiciously auspicious debut

Crime Wave’s world première was also its test screening; Paizs didn’t do one before. “It showed me a lot, in terms of what worked and what didn’t.”

Just before the film started, Paizs went up to the projector booth. “I asked the projectionist to play the movie loud. As loud as he could. Right up to the max. He sort of shook his head, but then he said OK, and he cranked this dial on the wall.”

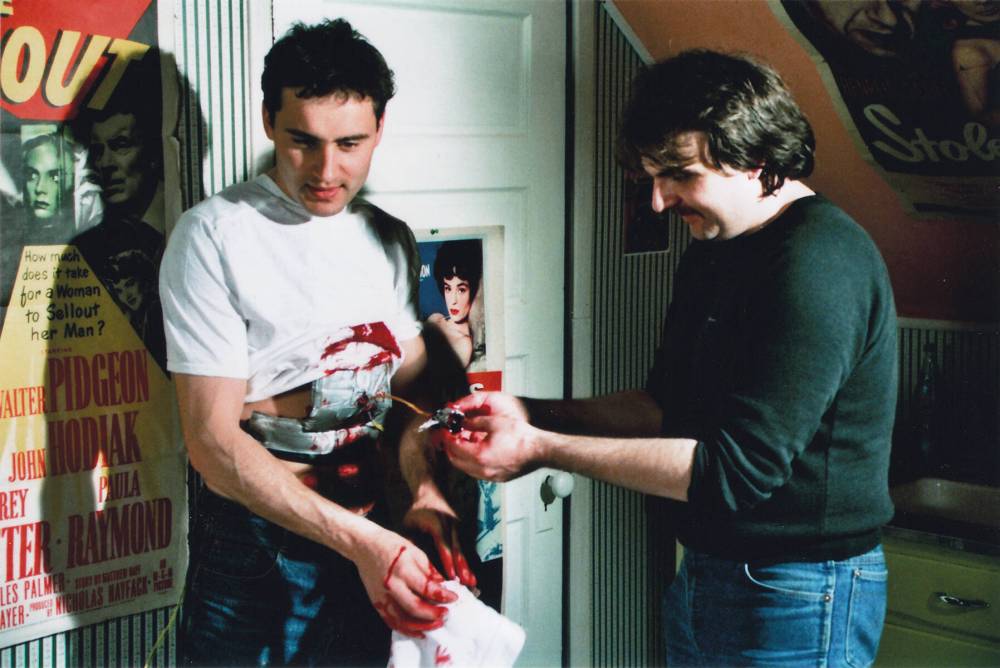

SUPPLIED John Paizs (left) and David Peter.

The room was “electric,” Paizs says. All the jokes were landing, and Paizs recalls waves of laughter. “Just around when there was this turn in the story, around the 20-minutes-from-the-end mark, something awful happened.”

The theatre lost its sound. A circuit had blown, or something like that, and the sound system went silent. For the next half hour, the projectionist tried to fix it. Meanwhile, patrons went to the lobby for a smoke.

When the sound returned, most of the audience hadn’t. “And this was exacerbated by the fact that the story took such a huge tonal shift in the final 20 minutes.” Paizs’ bubble was burst, and the director was fittingly deflated.

Head hung low, he loped back to his hotel, where the next morning he received a surprise.

One day later

“I was crossing the lobby and someone came from the press room, and said, ‘Have you seen Jay Scott’s review in the Globe and Mail?’’

He hadn’t, so someone handed it to him. Headline: Winnipeg director can’t quite end it all: Half-cooked Crime Wave.

“And I thought, what the f—? Why are you showing this to me?’” Paizs remembers. “This was exactly what I was afraid of. And she said, ‘No, the reviewers don’t write the headlines. Just read it.”

JESSICA LEE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Winnipeg director John Paizs in Middle Gate, where he made his debut feature film, Crime Wave, in 1985.

What Scott had written floored the young director. “If the great Canadian comedy ever gets made, Winnipeg director John Paizs … may be the filmmaker to do it,” the critic opened. “Paizs has a unique, off-centre sensibility. When he’s cooking, he sizzles.” He compared the film’s narration to that style used in Badlands and Days of Heaven, a pair of epic visual poems from American filmmaker Terrence Malick.

But Scott, the multiple National Newspaper Award-winning critic, who died in 1993, had one critique that rang particularly true to Paizs, who went on to work with the iconic Canadian comedy troupe the Kids in the Hall and to forge a fruitful career in film.

“He said the last 20 minutes or so does it in. Something along those lines,” the filmmaker says.

“I think he was right. It was the audience’s reaction, combined with Jay Scott’s review, that convinced me, maybe on the spot, to redo from scratch that last 20 minutes.”

That’s it: back to Winnipeg

Paizs had worked his tail off on that first cut, so he took Scott’s criticism — and praise — to heart. The director returned home, where he’d made and shown every film he’d produced to that point.

Paizs began his career as a teenager, focusing largely on short animation films, the lengths of which were a function of a lack of money and spare time.

He had his first proper studio in a St. Boniface warehouse his dad’s construction company owned. Paizs’ mother sewed costumes, and his parents let him use their house for shoots.

SUPPLIED Darren Bullerwell (left) and Shawn Wilson prep an exploding head.

But in 1981, the St. B building burned down, destroying most of what Paizs had made since he started making art as a student at St. John’s High School.

He initially wanted to be a comic-book artist, or an animator. He made an animated short called The Dreamer, which in 1978 earned recognition from the British Film Institute. But animation had limits Paizs found disconcerting.

“That was three minutes of film, and it took me over two years to make,” he says. “In a two-year span of time, I would have liked to have produced more work.”

He then went on a bit of a tear on live action shorts, including The Obsession of Billy Botski, which had its debut in 1981 at the Festival Cinema on Sargent Avenue, with former Winnipeg Film Group executive director and filmmaker Greg Klymkiw as programmer. “Before it was the Festival, it played — I don’t know if it was hardcore pornography or just nudies,” Paizs says.

SUPPLIED Tom Fijal perched on what is referred to as ‘Our Very Primitive (and Super Unsafe Looking) Camera Car’ during the filming of Crime Wave.

That film was an educational experience for the Paizs, who grasped the potential that existed within the constraints of budget, time, and space.

For a scene in Botski, Paizs and his crew had to transform a meeting room into a motel room. “I had three square feet of carpet and by moving it around the room, you have the illusion of a fully carpeted motel room,” he told the Free Press in 1981.

“It was the first movie where I established what would soon become my signature style: working in 16mm with a Bolex, and I had a very stripped-down approach,” he reflects, 41 years later. “I wouldn’t move the camera. I would post-sync all of the sound. It was narration heavy, and I shot it in this tableau style.”

A self-taught director — with plenty of mentorship — he learned to make films by making do, and by making best use of the city around him.

The city as a star

After struggling with two complete screenplays, Paizs started writing Crime Wave in 1984 at his Wardlaw Avenue apartment.

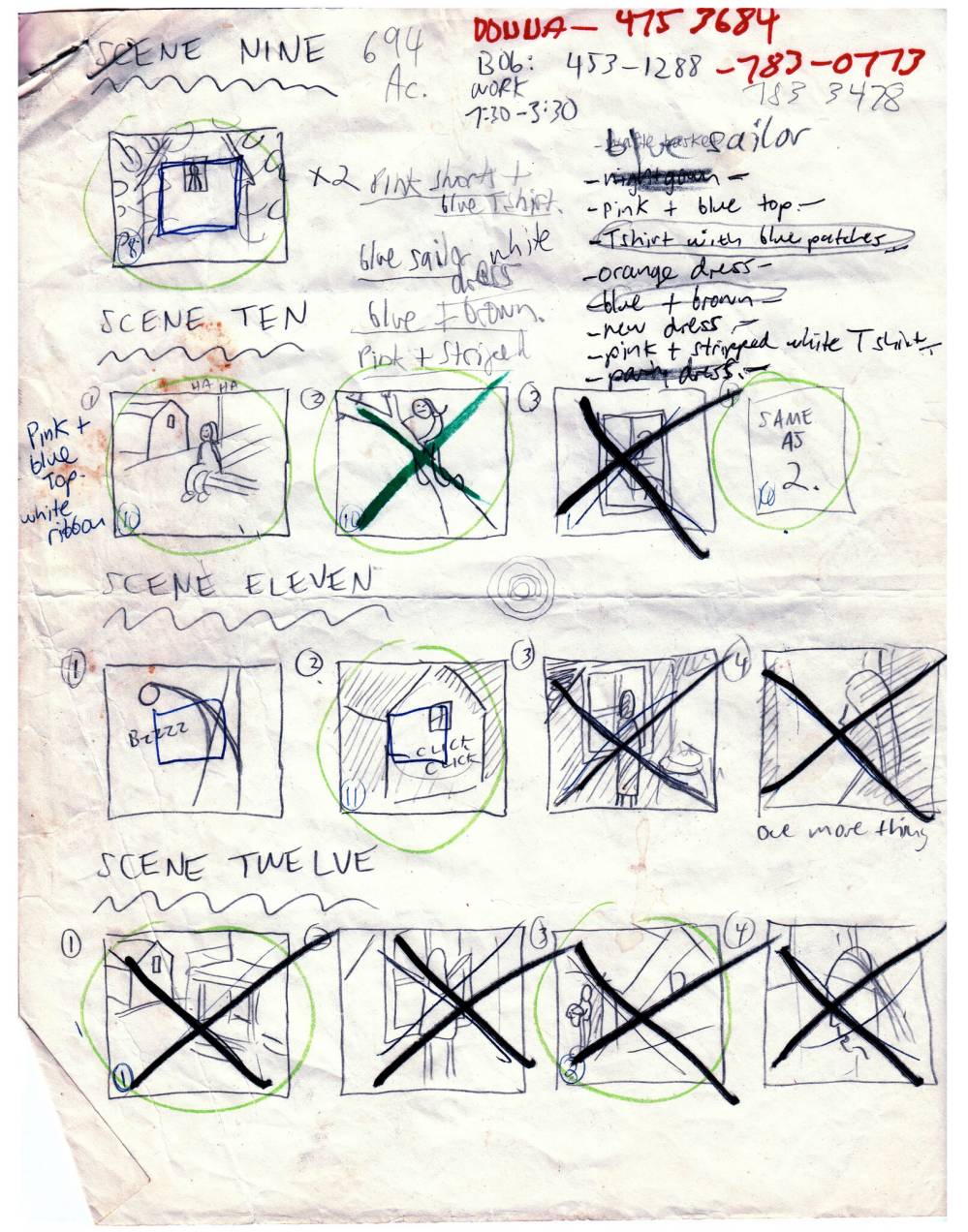

SUPPLIED A storyboard from Crime Wave

Inspired by the music of Talking Heads and Devo, Paizs set out to write a film that was short, poppy and paid tribute to bygone eras with an added edge and acerbic bite.

When finished, he assembled a murderer’s row of budding local talent, including composer Randolph Peters and story editor George Toles — who contributed “gold” scenes for the revised ending — and a cast of non-professional actors including Tea Tanner, Donna Fillingham and Bob Cloutier.

The film begins with an outlandish sequence of professional impersonators of Buddy Holly, Sid Vicious, Elvis and the like, but the montage is interrupted by a girl speaking directly to the camera, who introduces a character (played by Paizs) intent on making the “greatest colour crime movie ever.”

His leading actress arrived to Paizs as a godsend in an insect costume.

SUPPLIED Eva Kovacs as Kim Brown.

“In the biggest fluke ever, my parents invited me to go to their church for a revue featuring the kids of the parishioners, and Eva Kovacs was one of them,” Paizs says of Kovacs, who later became an anchor for Global News. “She was in this bug costume that had a couple extra hands sticking out the sides, and she recited this elaborate poem.”

“It was eureka,” Paizs says. Better yet: her dad was an engineer at Paizs’ father’s company.

Eighteen months later, Paizs was reading Jay Scott’s review and soon would be rewriting, reshooting, and recutting the ending completely. That version — restored from Paizs’ own 16mm print by Matchbox Cine, in collaboration with the film group — screens Friday at Cinematheque.

An unlikely legacy

Since that night in Toronto, the original cut of Crime Wave has since become totemic in some independent film spheres, perhaps nowhere more so than in Winnipeg. Cinematheque refers to the film in its marketing materials as “one of the greatest films ever made.” That notion makes Paizs laugh when he hears it.

Jaimz Asmundson, the theatre’s programming director, reiterated his opinion with regard to the original cut.

“Crime Wave was unlike anything my young mind had experienced,” says Asmundson, who saw the film as a child at Cinema 3 on Ellice Avenue. “It opened my eyes to the possibilities of creative ingenuity with limited resources, and that filmmaking wasn’t some lofty idea that only happened in Hollywood — great films were being made right here in Winnipeg.”

SUPPLIED Camera operator Jon Coutts (from left), soundman Gerry Klym, hair and makeup person Szilvia Kovacs and actor Eva Kovacs.

Asked by a reporter what it means to have made this film in Winnipeg, Paizs is stopped in his tracks.

“Jeez,” he says, after several seconds. “I guess we could’ve made this movie somewhere else, in the same way, on a very small budget, virtually next to nothing, and using all amateur talent. Honestly I don’t know what to say to this one. It’s not a hard question. Why am I drawing a blank?

A few more seconds.

“I don’t know what to say,” he says. “It means everything to me. But what kind of an answer is that?”

ben.waldman@winnipegfreepress.com

If you value coverage of Manitoba’s arts scene, help us do more.

Your contribution of $10, $25 or more will allow the Free Press to deepen our reporting on theatre, dance, music and galleries while also ensuring the broadest possible audience can access our arts journalism.

BECOME AN ARTS JOURNALISM SUPPORTER

Click here to learn more about the project.

Ben Waldman is a National Newspaper Award-nominated reporter on the Arts & Life desk at the Free Press. Born and raised in Winnipeg, Ben completed three internships with the Free Press while earning his degree at Ryerson University’s (now Toronto Metropolitan University’s) School of Journalism before joining the newsroom full-time in 2019. Read more about Ben.

Every piece of reporting Ben produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.