Built-in immortality Even 91 years after his death, architect Max Blankstein lives on in the glory of the Uptown Theatre and other creations distinctive enough to warrant a book about his life’s work

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 21/12/2022 (1172 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Max Blankstein died 91 years ago. So how is he still living in Winnipeg?

In 1874, he was born in Odesa, a key cog in the Pale of Settlement, where his father worked in the business of building. In Odesa, Jewish people were restricted in their career choices, with antisemitic laws barring entry to many professions. But that was not the case in the trade where Mayer Kritchmar — who would soon change the family name to Blankstein — found success.

His son, Max Zev, was a brick off the old apartment block.

Several buildings in Odesa are attributed at least in part to Blankstein’s expertise; The Tanasevich Block at 30 Chervonoslobis’ka St., and at least two other Blanksteins still stand in the Ukrainian port city.

Despite there being no records indicating he received professional training in his native land, Blankstein was already an architect — an age-old job which in the 19th century had only recently become a recognized profession in many countries around the world.

Though Blankstein’s career was progressing, many benefits of staying in Russia were counteracted by serious risk.

Odesa was rounded out by a disproportionately high number of intellectuals, writers and artists from other parts of what was becoming modern Europe. And by 1897, more than one third of Odesans were Jewish. It was in a sense the perfect place for a young architect to sketch out the schematics of his life.

But antisemitic pogroms roiled the city’s Jewish community five times, with the attack in 1871 — three years before Blankstein’s birth — earning the ignominy of being the first attack wherein locals joined in on the violence.

In 1905, the most violent pogrom in Odesan history up to that point happened, with hundreds of Jewish residents murdered and thousands more injured.

But Max Blankstein was not there.

A whole new shtetl

The cycle of Blankstein’s life and career is carefully laid out in city historian Murray Peterson’s essential Max Blankstein: Architect. Published this month by the Winnipeg Architecture Foundation ($35, winnipegarchitecture.ca), the book is a classic and dream-like fable of the staunch mentality and work ethic required of newcomers in an often unforgiving new land.

When he arrived in Manitoba in 1904, “Mordechai” Blankstein had a goal in mind — to work hard enough, fast enough and, ultimately, earn money enough to send for his children, his sister-in-law, his father, his mother-in-law, and his wife, Esther Goldin.

It was in some ways a matter of life and death.

In 1904, the Russian and Japanese empires engaged in war on the Pacific Coast, Peterson notes, and Jewish people or other unwanteds became military pawns and patsies. “The rising antisemitism in the Russian Empire of the early 1900s found expression in its expanded conscription of Jews for the war,” writes Peterson. Children under the age of 18 were often ensnared in military service, and Jewish people were four times as likely to be forced into a war that killed 2,500 Russian soldiers.

RUTH BONNEVILLE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Murray Peterson, author of Max Blankstein: Architect, and Winnipeg Architecture Foundation director Susan Algie believe Blankstein’s architectural signature is most profoundly seen in the Uptown Theatre on Academy Road.

In October 1905, in Odesa, hundreds of Jews and non-Jews were murdered, thousands more were injured, and over 1,600 Jewish-owned or rented properties were damaged or destroyed by antisemitic mobs. The city’s governor estimated the number of casualties to be 2,500.

“Indeed, no other city in the Russian Empire in 1905 experienced a pogrom comparable in its destruction and violence to the one unleashed against the Jews of Odesa,” Jewish historian Robert Weinberg wrote in 1992.

Undoubtedly, Max Blankstein knew places that were burned and knew people who were wounded, whether mortally, superficially or psychologically, during the attacks, which lasted four days.

But neither his wife, nor his children, sister-in-law, mother-in-law or father were killed in the Odesa pogrom of 1905.

By 1907, they would all be Manitoba residents, thanks in large part to their relative, the architect.

The right time

Blankstein didn’t know it, Peterson writes, but he arrived in the Prairie capital at precisely the right moment. Incorporated in 1873, the city of Winnipeg was expanding at a rate which made it one of the most important nodes of business, entertainment and public life in all of Canada, not just in the West.

Meanwhile, the Jewish population was growing in tandem, creating an influx of merchants, professionals, educators and religious officials, each of them sharing not only a cultural background, but a common need for accommodations: every rabbi needed a pulpit, and every butcher needed a shop. Group economics were at play, especially in the North End, where Blankstein eventually set up his home office at 131 Machray Ave.

SUPPLIED Max Blankstein’s home office, at 131 Machray Ave., was where he drafted much of his work.

As an architect, Blankstein’s output dovetailed with the expansion of the city, and its Jewish population. In 1905, he designed the Chesed Shel Emes, the Jewish funeral chapel. In 1907, he designed the Adas Yeshurun Synagogue on the 200 block of McGregor Street. The same year, Max designed the Aikins Court apartment building, constructed by a contractor named J. Shrem for an owner named J. Freedman. Now known as Pritchard Court, the 115-year-old building still stands.

Quickly, Blankstein’s workload quadrupled, as did the variety and scale of his designs, which he drafted from his home on Machray, with his children watching.

“His office … was a place of fascination for his children, who spent much time playing and drawing there,” Murray Blankstein write in the foreword, the oldest of Max Blankstein’s nearly 100 grand- and great-grandchildren.

His early days in Canada were not without personal tragedy: only one year after Blankstein brought his wife, along with their two young children and her extended family to Winnipeg from Russia, the 25-year-old Esther Blankstein died. He then married her sister, Laika, and the couple had five children. In 1907, more of Blankstein’s relatives arrived, including his father and his father’s second wife, his niece, and his sisters.

In 1910, Blankstein made official what he had unofficially been for his entire adult life: he registered as an architect.

The first Jewish one in Canada, as far as Peterson and Winnipeg Architecture Foundation director Susan Algie can tell from their extensive research.

A pair of palaces

With the December wind blowing, Peterson and Algie stand beneath the marquee of Max Blankstein’s final, and arguably most famous, contributions to the Winnipeg architectural record: the Uptown Theatre, still standing nearly a century after his death.

Blankstein had a bit of good fortune in the company he kept, and after starting his career — and building his wealth — by taking on an enormous number of small contracts, as well as buildings for the Jewish community, he began to expand into commercial properties. The blossoming world of cinema was the beneficiary of Blankstein’s grand designs.

TRIBUNE ARCHIVES Designed in 1912, Max Blankstein’s Palace Theatre, on Selkirk Avenue, would eventually seat 800 patrons.

In 1913, the Rex — Winnipeg’s first motion-picture-only facility — opened, Peterson writes.

“If there was one building type that Max Blankstein excelled at … it was theatres,” the historian writes.

If there is one thing that Peterson does well, it is to describe with clarity and skill the architectural sensibilities of the men and women who designed this city’s built environment. Blankstein’s strength was in designing “Moorish village scenes” where “the ceiling became the night sky with twinkling stars and drifting clouds,” Peterson writes. “It made going to a movie an event.”

ETHAN CAIRNS / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS In 1912, Max Blankstein designed the Palace Theatre on Selkirk Avenue.

Blankstein made friends with a fellow Russian Jewish immigrant named Jacob “Jack” Miles, born in 1887 and settled in the North End in 1905, where he worked as a painter. Miles was a forward-thinker: he’s credited with introducing Harley Davidson motorcycles to Winnipeg. And he quickly became one of the country’s most successful independent theatremen: at his peak, he controlled 18 local theatres.

It was through Miles that Blankstein got into the theatre business, and in 1912, he designed the Palace Theatre on Selkirk Avenue, “festooned with ornamentation and decorative lighting, with seating for nearly 800 patrons after an expansion.”

In the ensuing years, Blankstein’s contracts continued to pile up, and as a solo practitioner, he designed dozens of projects. But Winnipeg’s building boom was about to go bust. About $16.5 million in building permits were taken out in 1912, but by 1915, that was reduced to one tenth.

Like most architects in the city, Blankstein struggled as an economic downturn began in Western Canada, and by the mid-1920s, Peterson writes, he could not afford to pay his annual dues to the Manitoba Association of Architects.

He eventually managed to pay, and in 1931, took on one final contract for Miles for the Uptown.

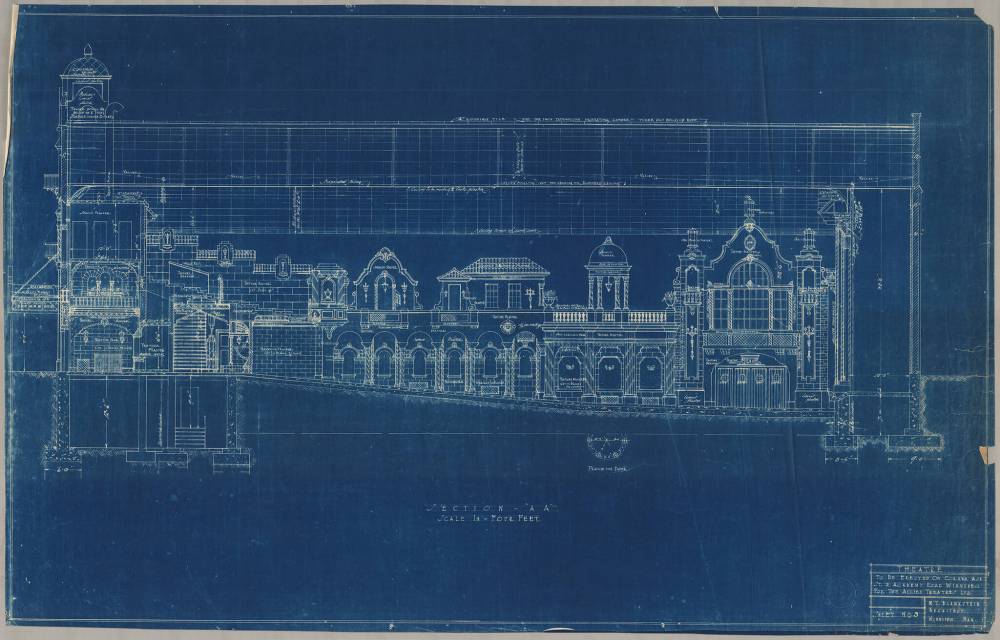

SUPPLIED The original drawings for what would become the Uptown Theatre, which opened its elegant doors to the public in 1931, a week before its architect, Max Blankstein, died at the age of 57.

Peterson and Algie admire the theatre — converted in the 1960s to a bowling alley, and in 2021 to loft apartments — and its Moorish ornamentation, clad in a yellow stucco with other colours mixed in; that’s a Blankstein signature, Algie says.

Blankstein’s design for the Uptown was grand, and while its domed roofs, rounded windows and Juliet balconies recall a fairy tale, Blankstein’s theatre evokes a spirituality and mysticism reminiscent of a house of worship. A temple.

He died on New Year’s Eve 1931, at age 57, only seven days after the Uptown’s doors opened.

Still standing

Blankstein’s architecture continues to tell the story of Winnipeg, and there is perhaps no better encapsulation than the Palace and the Uptown. On Academy Road, the Uptown was given a glitzy and extensive renovation in 2021. Meanwhile, the U of M-owned Palace on Selkirk Avenue faced demolition, a fate staved off by community intervention.

SUPPLIED Max Blankstein in his later years.

And even though Blankstein has been dead for 91 years, his architectural legacy is still ongoing.

His daughter Evelyn was the second female student to graduate from the University of Manitoba’s architecture program, working for over 40 years in a male-dominated field. His son Isaac entered the theatre business, and later was a co-founder of Great West Development Co. Another son, Cecil, took on his father’s practice after his death, later joining with architect Lawrence Green to form Green & Blankstein Architects, which became Green Blankstein Russell, or GBR, one of the most influential firms in Winnipeg history. Max’s youngest son, Morley, joined GBR, and then was a co-founder of a firm that is today known as Number TEN Architectural Group.

One-hundred-and-eighteen years after his arrival in Winnipeg, Max Blankstein still lives here.

ben.waldman@winnipegfreepress.com