Pieces of the past Interlake artists’ Slo-Toons are whimsical little works on wood that deliver comforting shot of nostalgia

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 04/07/2022 (1251 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Shaun Morin and Mélanie Rocan live in a present bursting with the past. Their kitchen shelves are lined with cookie jars in the shapes of walruses or lambs, alongside bottles once filled with sodas that haven’t been made since before the couple was born. Little knicknacks, everywhere.

With their young daughter, Eloise, the artists would rather watch Peter Falk solve a case on Columbo than sit through whatever Netflix is pushing. They like what they like and they aren’t afraid to show it.

At their property, just past Camp Morton in the Interlake, the couple has built what can only be described as a residential wonderland. On every square centimetre is the welcoming imprint of whimsy, and an invitation to return to the innocence of youth. There is a handmade ring-toss game, a giant cutout of Spider-Man, and on the wall of one of several outbuildings, a hand-painted wooden Woody Woodpecker: you can almost hear the Heh-heh-heh-HEH-heh.

Morin and Rocan are serious artists. They’ve both had success in the prestigious RBC Painting Competiton, enjoyed exhibitions at galleries both local and national, and are graduates of the University of Manitoba’s School of Art, where Rocan was an instructor.

They’re members of the Two-Sicks, a local street-art collective that broke new ground in Winnipeg with a blend of street and fine art in the aughts, “pre-fabbing” artworks and “nailbombing” them to fences and walls throughout the city. Their skills, developed over two decades as professional artists, are extensive, ranging from graffiti to oil paintings: they could probably create anything if they set their minds to it.

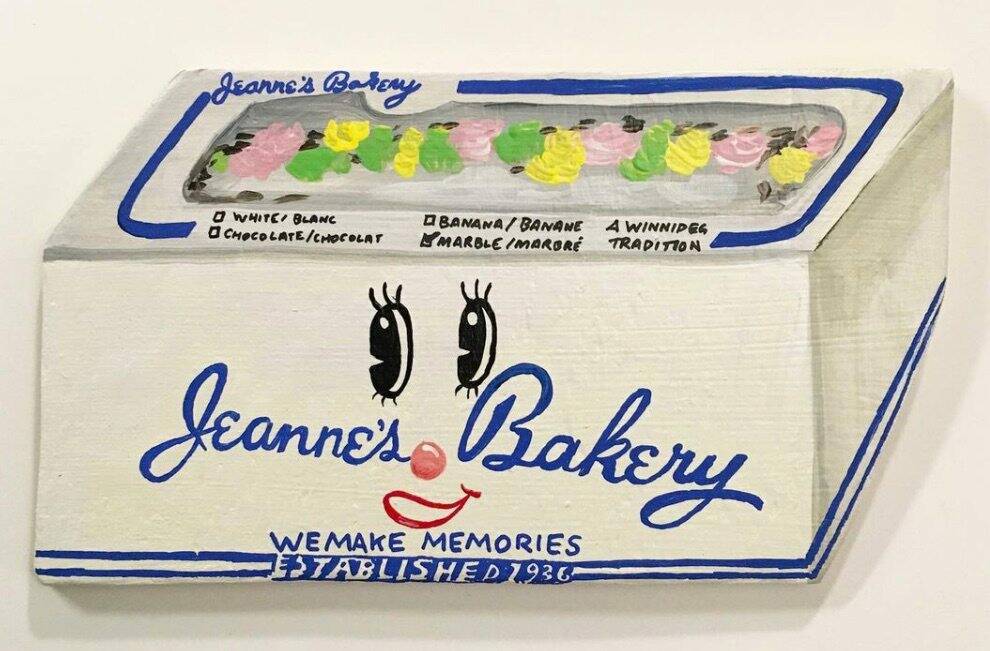

So why are they painting cartoonish Hawkins Cheezies, wide-eyed pieces of Bubblicious gum, rosy-cheeked cans of SPAM, smiling slabs of Jeanne’s Cake and concerned bottles of China Lily soy sauce on pieces of plywood, then selling them for less cash than a nice dinner for two would cost these days?

For one thing, they are inspired by their surroundings — and just look at the world they’ve created, which oozes with unfettered nostalgic joy. For another, they are inspired by what they know. They try to distil those components into their work to create a pure expression of themselves, and a reflection of what matters to them and gives them feelings. Ultimately, they want to connect with people.

Enter Slo-Toons.

In April 2020, a few things happened. Morin left his job as an addictions counsellor, and the pandemic forced the world into a dark, depressing epoch marked by uncertainty about the future both near and far. Naturally, as he and Rocan have always done, they sought comfort in the past — the only part of life cushioned by any semblance of certainty. What’s done is done.

Using Instagram (@slo_toons) Morin began posting woodcut artworks of crude and eye-popping faces, selling them for $45 apiece. The idea was to create affordable wall art, as accessible and appealing to the millionaire as the student eating bowl after bowl of instant ramen.

Tired of feeling hemmed in by the often stuffy world of galleries, Morin wanted to lean in on his roots of Mad magazine and Wacky Packages trading cards to make, with Rocan, art that felt both highly specific and in some ways universal.

“There’s high art, and then there’s what they call low-brow,” Morin says as he fans the flames of a bonfire with a piece of cardboard that reads, in his own writing, “Oxygen.” “My whole life is spent learning to try to walk to the centre point. That is the essence of what we’re trying to do. Finding that place is hard work.”

Rather quickly, the cartoon faces were transplanted onto s’mores, socket wrenches, Pez dispensers, table-hockey players, phone booths, Care Bears, metal lunchboxes, a DeLorean and ice-cream cones.

Sitting in front of a shelf overflowing with hockey cards, comics, dollar-store LPs and tiny figurines, the couple created a rather human assembly line, embracing their nostalgia to create lovingly rendered images of the world that existed before social media, before streaming video, when self-driving cars were the stuff of science fiction.

“Not every piece will be appealing to every person but you would often be surprised at which pieces feel as if they speak to you very directly,” says Toronto’s Ginette Lapalme, who has several Slo-Toons on display at her Toutoune Gallery. “It was exciting to bide my time and wait for the right moment to pounce on the pieces that really felt like they should belong with me. I first acquired a bag of my favourite childhood chips (Hickory), a bunch of grapes, an inhaler and, eventually, a terrific Wilma Flintstone with mouths for eyes.”

Almost 2,000 toons have followed. Right now, there is clearly an appetite for the past.

“It’s almost like coming full circle,” says Rocan, who met Morin in 1999. “You go through many things, and then finally you can go back to the beginning.”

● ● ●

Nostalgia can roughly be translated as “a pain associated with home,” but is often meant colloquially as a rose- coloured spectrum through which the past is seen by modern eyes. In his 2020 book On Nostalgia, writer David Berry says the titular feeling is considered as much a coping mechanism as it is a reflexive condition. Usually, the “pain associated with home” refers to a yearning to return to its comforts, sometimes associated with soldiers away at war in faraway trenches.

In the early stages of the pandemic, the yearning was to go anywhere other than home, and the common inclination was to surround oneself with insulation — reruns, escapist fiction, sourdough — from the dangers lurking outside.

It was in that state that I bought my first Slo-Toon — a cloud wearing a top hat who looks like he’d had enough. My second was a Montreal Expos hat that smiles at me from above my desk. They sum me up pretty well.

Morin says something that doesn’t need to be said: the onset of the pandemic was a scary time. He felt unmoored. He was a little bit depressed. He was concerned.

In the Slo-Toons studio, he and Rocan and Eloise, who often helps her parents if she isn’t drawing cartoons of her own, created their own bubble of comfort. Eloise fell in love with old Strawberry Shortcake cartoons. Morin and Rocan fell back in love with the things they adored growing up in the 1980s, which it turned out they never really outgrew.

They’d sit at their table — morning, afternoon and night — and create little pieces that would brighten up walls across the province and country: they painted Gumby and cupcakes and teacups and pizza slices. A can of Bush’s Baked Beans, a gumball machine, mixtapes, Coffee Crisp, batteries, Swiss Army knives.

They also painted Signs of the Times: teardrops that said “It’s Never Too Late for a Good Deep Heartfelt Cry,” or an inviting hearth, asking to “Pull Up a Chair and Stay Awhile.”

At first, the couple was a little bit surprised by the verve of their customers, who snapped up paintings quickly and with great frequency: some buyers have 10, or even 20, Slo-Toons in their personal collections.

The brilliance of the toons is the feeling Toronto’s Lapalme described: that certain pieces were simply made for you.

“A bus driver bought one of our (Winnipeg Transit) buses,” says Morin. “What an honour that was.”

The daughter of the owners of St. Vital burger stop Mrs. Mikes — “I think it used to be called Dairy King when I was a kid,” adds Morin — bought the Slo-Toon of the restaurant for her parents. And then she asked for one for herself. A similar story played out at Red-Top. A member of the City Bread family bought Morin and Rocan’s loaf of plywood rye.

For Morin and Rocan, the response has been overwhelming: as a primary source of income, the small paintings have merged love, hobby, memory and commerce to support their family through the pandemic, as trying a time for working artists as has existed in recent memory.

It’s also been an exercise in understanding: who they are, what they care about and what they want to be their legacy.

“These are little pieces of us, and the more they get out there, the more I feel like we’re giving birth to some kind of love or something,” says Morin, sitting by the fire sipping from a cup covered in strawberries. And if they don’t sell? They put them up in their own home, or in their self-built gallery that sits in their front yard.

Nostalgia is often dismissed, sometimes with good reason, for glossing over reality in search of what’s lost. Slo-Toons do not do that: they ask why we lost those things in the first place. If we loved something when we were children, or teenagers, or earlier versions of ourselves, does that inherently make that thing too quaint, too childish, or too innocent?

“I feel that there’s something special in that what we do feels so honest and natural,” says Rocan.

“I think that there is a strength in nostalgia, in that there’s an innocence to it,” says Morin.

When did innocence become such a bad thing?

ben.waldman@winnipegfreepress.com

Ben Waldman covers a little bit of everything for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.