Drum roll please… Bill McMahon has been sitting behind a kit for 65 years, keeping the beat in venues and for bands all across the city

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 24/06/2022 (1264 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

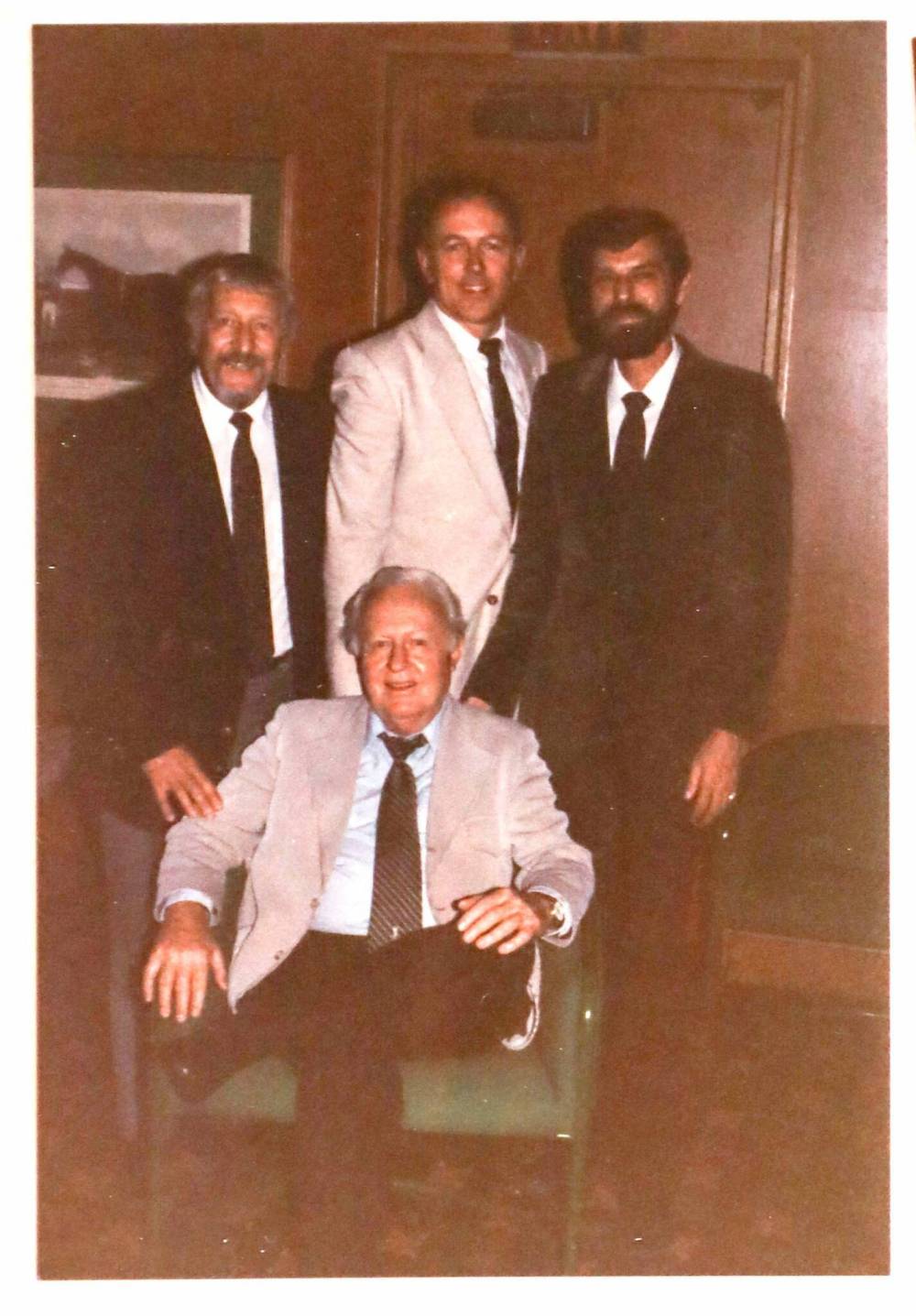

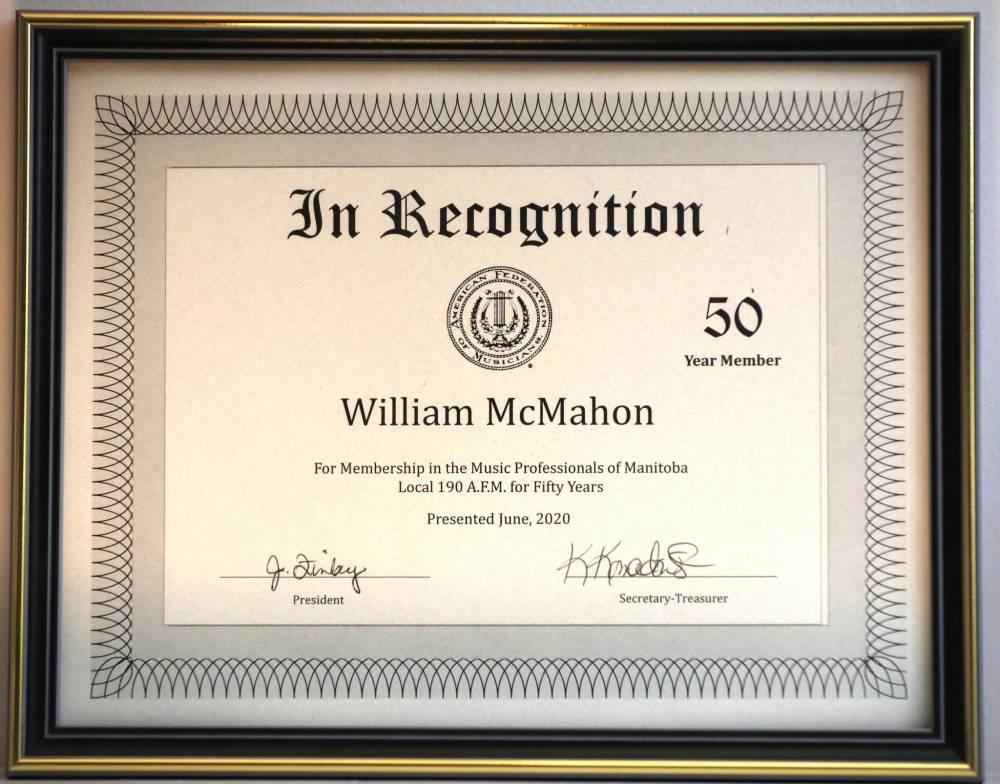

Bill McMahon has a few things in common with ex-Beatle Ringo Starr. First off, both men were born in 1940; McMahon turned 82 on May 11 and Starr will follow suit July 7. Second, each took up the drums in 1957, at the age of 17. Furthermore, neither appears ready to park his cymbals (did we mention each of them pounds away at a similar-looking Ludwig drum set?) any time soon. Starr, in fact, will roll into Winnipeg this fall with his All-Starr Band, for a scheduled performance at Canada Life Centre on Oct. 17.

That said, there was a period earlier this year when McMahon, a member of the highly respected jazz outfit, the George Reznik Trio for 40-plus years, was in a bit of a pickle, concerned he wouldn’t be able to play drums again.

McMahon was shoveling snow off his two-tier deck in January when he tripped, causing him to tumble down a flight of stairs. He knew he was hurt, as the pain was “something else,” he says, seated on a couch in the Charleswood split-level he shares with Diane, his wife of 61 years. Still, he chose not to tell her what occurred when he finally made his way inside, opting instead to head to the rec room to pour himself a shot of rye. OK, two.

He was forced to come clean the next morning, and ultimately agreed to let their son Ken drive him to the hospital. X-rays revealed that in addition to damaging his left rotator cuff, he’d broken nine ribs.

“I spent seven or eight days with an epidural in the top of my back; there were giving me opioids and I was swinging pretty good for about a week,” he says with a chuckle.

A few days after returning home, McMahon received an email from Tony Siwicki, the owner of the Silver Heights restaurant, where, pre-COVID, he had been performing every Saturday afternoon under the banner, the Bill McMahon Group. Siwicki was hoping to restart things, to which McMahon shot back, “Oh, cripes, I don’t know if I can.”

“To make a long story short, I finally took the drum chair again on May 7, straight from an appointment with my (athletic) therapist,” he says, noting his jazz ensemble, which has a rotating cast, has a strong following in the city and was warmly greeted by a packed house. “I’m not going to lie, I felt pretty rough the next morning, but that was mainly because I don’t back off when I play, I give it everything I’ve got. We’ve since taken a break for the summer, the same as we always did, but come fall, my goal is to be back at it, every weekend.”

Born in Winnipeg and raised on a farm in the Dauphin area, McMahon was living in the city in 1957 when he attended a house party in St. James with his older sister. Her boyfriend was part of a band providing the entertainment, and McMahon found himself studying the drummer as the group whipped through one Elvis Presley song after another. “You seem to be digging what’s going on,” the drummer remarked to him between sets. Did he want to give it a try, himself?

You bet, he replied. When he was finished, another person at the party complimented him on his technique. How long had he been playing, the fellow wanted to know? “About 15 minutes,” came McMahon’s reply.

“I can’t say why, but it just came naturally to me, like I’d been doing it all my life,” he explains. “Two months later I had my own drum kit, and not long after that, I was playing in the pubs with a guy named Benjamin Jones, who was originally from Jamaica, and did all the (Harry) Belafonte tunes.”

For years, McMahon, who left school in Grade 9, overhauled diesel engines by day, and kept the beat for umpteen different bands by night. Style of music was never an issue; he could play everything from rock and roll to western swing to rhythm and blues. He never took formal lessons, mind you, and vividly recalls an evening when he was enlisted to back up a pair of brothers, one a trumpet player, the other an alto saxophonist, for a wedding.

The setlist that night consisted primarily of songs made popular by Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass. Every three minutes or so the brothers would turn around and loudly instruct him to turn to whatever page of a provided songbook.

He did precisely as he was told. At one point, the guitarist leaned over to McMahon, to let him know the brothers were mightily impressed with his reading ability.

“I looked at him and said, ‘Who the (bad word) told them I could read music?’”

McMahon figures it was around 1969 when he began to fall in love with jazz music. Married with one son and another on the way, he heard through the grapevine about a pianist named George Reznik who was packing ‘em in every Sunday night, at a downtown night club. He headed there one evening, and was gobsmacked when Reznik, who by then had played with the likes of Louis Armstrong and Barbra Streisand, approached his table during a break, to see if he wanted to sit in with the band.

“Holy crap I was scared, but I guess things turned out OK because I spent the next 42 years — 25 of those at the Pembina (Hotel) every Saturday afternoon — playing with George,” he says of Reznik, who died in 2016 at age 86.

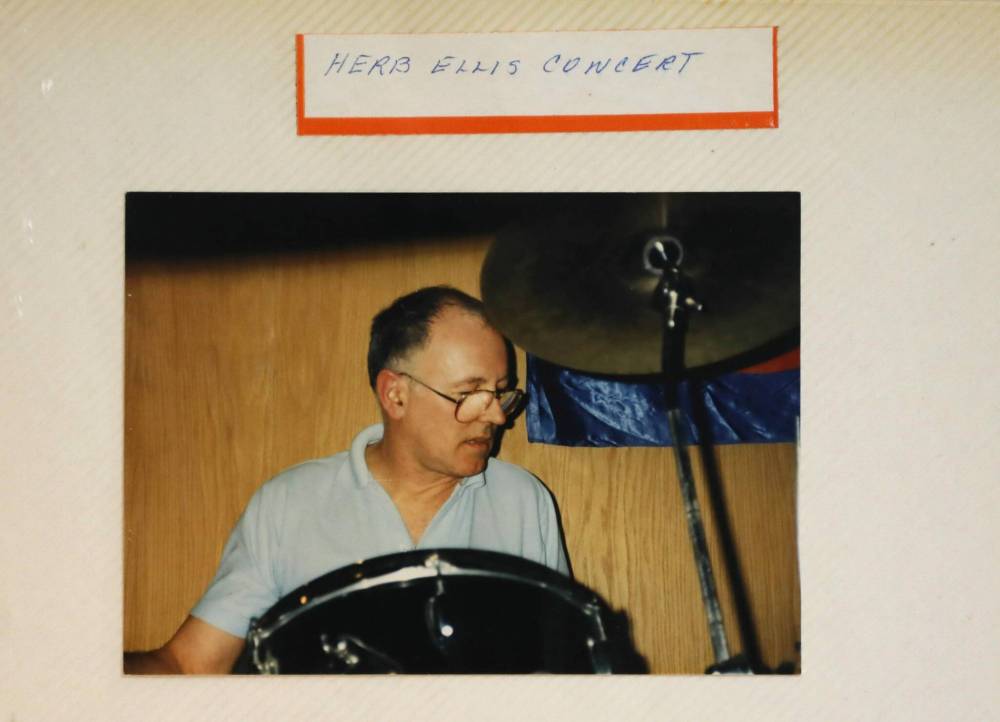

McMahon, who only retired from his job as a diesel mechanic seven years ago, calls it a tough question, when asked about moments from his musical career that stand out above all others.

He worked extensively with blind bass player Dave Drew in the 1970s, and says around-the-block lineups were a common occurrence, when the two enjoyed a six-month run at the Voyageur Inn, a 90-seat venue formerly in Fort Garry. It wasn’t just local jazz fans filling the chairs. One time they were joined on stage by pianist Earl (Fatha) Hines, who was in town for a show of his own, and later regaled them with yarns about working with jazz giants Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie.

Other benchmark moments include the multiple occasions the self-described hired gun backed up Chicago-born jazz songstress June (Pepper) Harris and more recently, Winnipeg blues singer Tracy K. Then there was the time his wife spilled a drink at an afterparty at the Centennial Concert Hall, and the person who brought her a refill was none other than Rock and Roll Hall of Fame member B.B. King, whom McMahon & Co. had opened for, earlier that evening.

“She didn’t even know who he was and there was me with my jaw on the ground, going ‘Holy s—, it’s fricking B.B. King.’”

Long-time bandleader Ron Paley was 14 years old when he played with McMahon for the first time in 1964. McMahon’s band was short an accordion player and Paley, who took up the instrument at age 8, was the only person available. (McMahon smiles, recalling Paley’s dad Walter, a musician in his own right, giving him explicit instructions when he picked Ron up: “No smoking, no booze and no broads.”)

“I remember that, too; he needed somebody to fill in at the last second, and somebody, I don’t know who, gave him my name,” says Paley, who last played with McMahon in the fall of 2019, six months before COVID-19 turned the world on its ear. “Through the years I’ve continued to play with him on and off, around my own schedule. Any time he calls, I’m always happy to oblige.”

Paley, who spent two years on the road in the early 1970s with Buddy Rich, widely regarded as one of the greatest drummers of all time, refers to McMahon as an “excellent player.”

“He loves music, he loves to play, and that’s clearly evident every time he sits down behind a set of drums,” Paley says. “I can’t count the number of times I went to see him with the George Reznik Trio, and though the jazz community misses George dearly, thank goodness Bill is still going strong.”

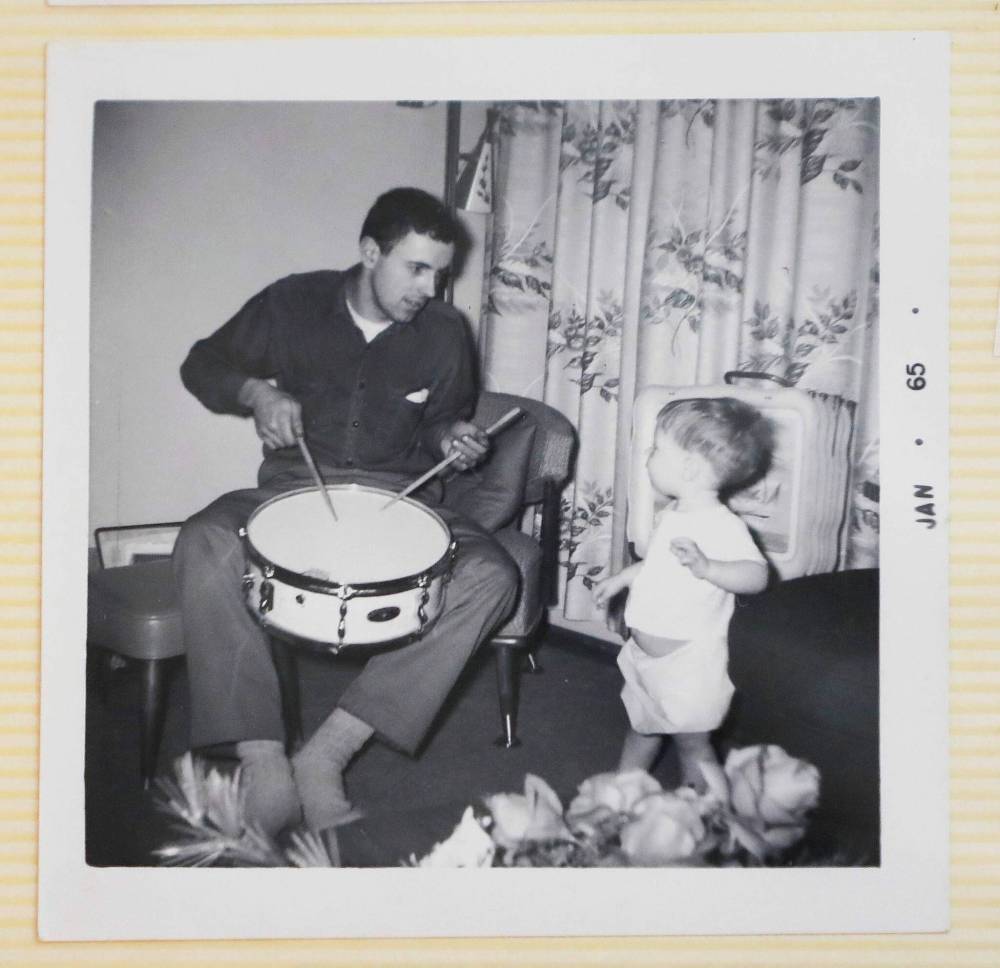

Ken McMahon, 50, was two years old when he started drumming on his mother’s pots and pans, and three years old when his dad began bringing his kit home from gigs, for him to use instead.

Ken, a veteran of the local blues scene who’s worked extensively with Brent Parkin and Big Dave McLean, says he learned a few drumming tricks from his dad, sure. What’s better is he was also on the receiving end of lessons focused more on what it takes to be a professional musician.

“Be on time for gigs, make sure your gear is in working order and above all else, maintain a level of humility,” Ken says. “One of the things Dad instilled in me is that, as a drummer, you’re just a piece of the puzzle; how if I was on stage with (Big) Dave (McLean), for example, there probably wasn’t anybody in the audience there to watch me, so I should know my place.”

Ken says his father would be the first one to tell you there are scores of drummers more technically sound than him. What the elder McMahon might lack in approach, he more than makes up for through his passion for music, his son says.

“Close your eyes when he’s drumming and you’d never know it was an 82-year-old up there.”– Ken McMahon

“It’s that deep affection for his art that has kept him going all these years,” Ken continues. “Close your eyes when he’s drumming and you’d never know it was an 82-year-old up there.”

For his part, Bill McMahon counts his blessings, as he continues feeling a little stronger every day. The word practice was never part of his vocabulary — he played so often, why would he ever pull out the sticks at home? — but he admits to playing along to CDs in his rec room the last few months, mostly to reassure himself he still has what it takes following his mishap.

“It’s the same as when George (Reznik) retired in 2013, and people kept wondering if I was next,” he says, leaning over to crank the volume on a favourite Thelonious Monk track. “People still ask that question once in a while, to which I say, ‘Hell, no. I’m just getting going.’”

david.sanderson@freepress.mb.ca

Dave Sanderson was born in Regina but please, don’t hold that against him.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.