The spirit of sharing Methods of discovering music shift with technology, but the joys stay the same

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 25/04/2022 (1323 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

At the risk of being all “kids today don’t even know,” kids today don’t even know.

When I was a teenager in the late 1990s/early 2000s — a.k.a. when the eldest members of gen Z were born — here were my choices if I heard a song I liked and then wanted to hear it again: I could save all my babysitting money to buy an entire $20 CD for one single; I could wait until the radio played it, or MuchMusic showed its accompanying music video, and then record either to cassette or VHS.

Or, I could attempt to download it via a file-sharing site accessed by dial-up, and then pray I didn’t accidentally download porn to the family computer and/or infect it with viruses, or get sued by Metallica.

(Some of you will say these are more choices than what was available to previous generations, to which I will say, “barely.”)

Now, though, The Youth can just hear something on TikTok and then go to YouTube or Spotify and there it is. Are we still saying “What a time to be alive”?

TikTok — and therefore, generation Z, since the two now appear to be synonymous with each other — in particular is often credited with reviving songs that end up going viral on the platform.

And you know what? I like it. I admit to initially bristling at the memeification of meaningful songs, but look: if I, a person with a full-on Pearl Jam lower back tattoo, can find the humour in the TikToks poking fun at Eddie Vedder’s impassioned incoherence on the song Yellow Ledbetter, anyone can.

As Richie Assaly notes in a Toronto Star piece looking at grunge’s TikTok moment, “beneath the meta-jokes and layers of irony, there seems to exist a genuine appreciation for the music.” I agree. TikTok is merely a new entry point for musical discovery.

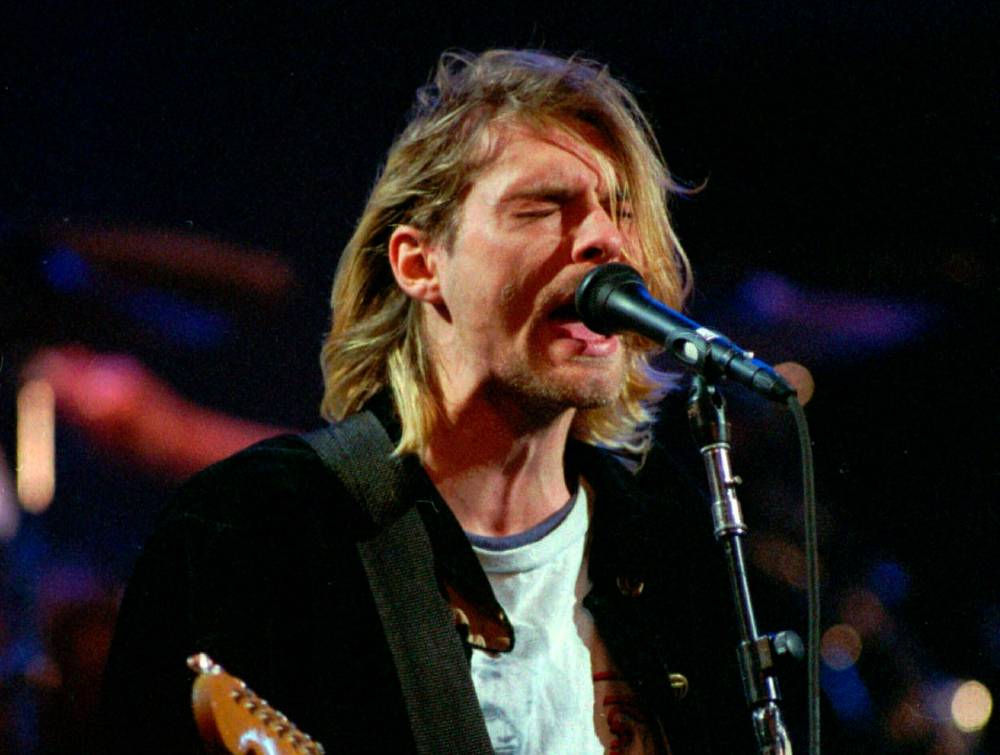

A lot of these bands, I would submit, also haven’t exactly faded from view, making their “revival” not all that difficult. Nirvana, for example, will probably always be someone’s favourite band — voices of a generation have the kind of endurance that can allow them to be voices of multiple generations. I was nine when Kurt Cobain died by suicide; I didn’t get seriously into Nirvana until I was 15. I’m not a gen-Xer, but discovering Nirvana — beyond what was played (and is still played) on the radio — felt like finding “my music” all the same. This is how legacies are built.

If you didn’t have the mythical older sibling or friend to help shape your musical tastes, or were too intimidated to chat up snobby record-store employees, finding non-radio music was a bit of a journey in the Time Before TikTok. Music magazines were good at describing music, but there was no mechanism to actually hear the “hard-charging” guitars or “squiggly” basslines.

But there were invisible tastemakers on whom we could rely, whether we knew it or not. Those guardians of cool, those unsung heroes of musical discovery: music supervisors on TV shows and movies.

In the early to mid-2000s, the high-water mark for music supervision was that of The O.C., the teen soap that gave us music nerd Seth Cohen (Adam Brody), whose great taste was bequeathed to him by music supervisor Alexandra Patsavas, who has worked on more than 100 films and TV series, including Gossip Girl, Grey’s Anatomy and Mad Men.

Seth Cohen’s fondness for indie rock helped propel many defining bands of the day — including the Killers, Death Cab for Cutie and Modest Mouse — to household-name status, and Patsavas’ work changed the way TV used music. For bands, it was no longer “selling out” to place your song in a hit show or movie. It was a pipeline to new fans. (Pearl Jam’s Yellow Ledbetter, by the way, was used in an episode of Friends, another ’90s phenomenon revived by gen Z.)

There are iconic examples from film, too. Many people of a certain age got into Pixies precisely because of the inclusion of Where Is My Mind? in the final scene of the 1999 film Fight Club. Something in the Way, one of the best songs on Nirvana’s 1991 album Nevermind, is having a similar moment right now, thanks to its use in this year’s The Batman.

TV’s influence can be seen all over the comments on YouTube videos. “Killing Eve brought me here.” “Good Girls brought me here.” Even car commercials can send someone scurrying online to figure out “who IS this?” Sometimes the songs are new; sometimes they are obscure tracks from 50 years ago.

I’m here for young people earnestly sharing their music finds on TikTok via series that have titles such as Oldies (oh no) You Should Know. How we share music has changed, but the spirit behind that act, not so much. It’s that itchy, “everyone has to hear this right now” feeling you get when you hear your new favourite song, the feeling on which many a mixtape/burned CD/playlist was built.

It doesn’t matter how old or new a song is — or to what generation it “belonged” — when it’s heard for the first time. And it’s always someone’s first time.

jen.zoratti@winnipegfreepress.com

Twitter: @JenZoratti

Jen Zoratti is a Winnipeg Free Press columnist and author of the newsletter, NEXT, a weekly look towards a post-pandemic future.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.