One final ride Remembering one of Winnipeg’s last streetcar drivers, and looking back on a different era

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 19/01/2022 (1422 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

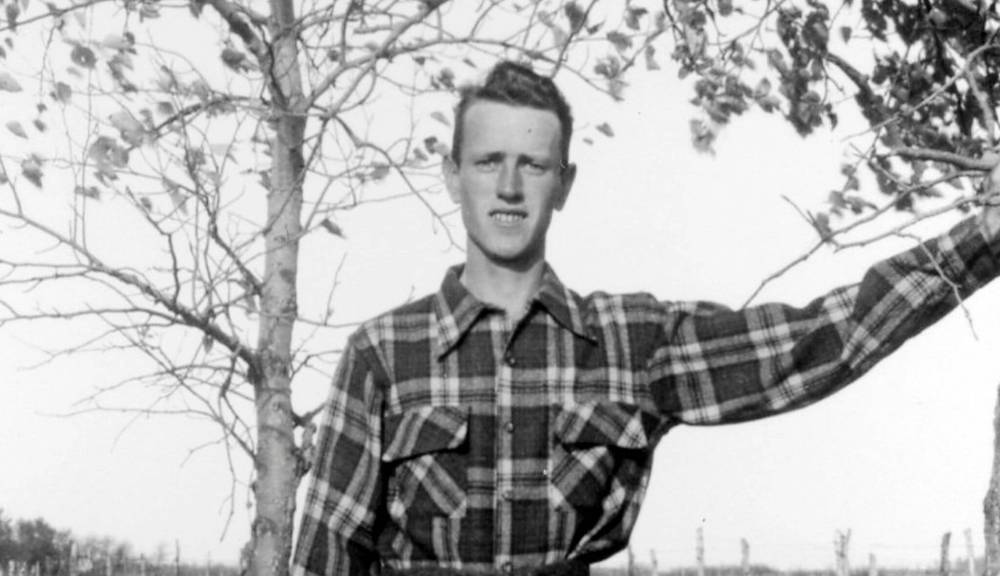

Brian Darragh did not know what he wanted to do for a career, but he knew perhaps the only thing better: exactly what he could never stand doing.

He did not want to sit down for a living. To be some body crouched behind a desk all day was not for him. On the farm, he spent most of his time outdoors, with teams of horses in the open air, his hands covered in a hard day’s dirt in Keyes, Man., just west of Gladstone. To be behind a desk meant to be inside, and to be inside was out of the question. He was stuck for ideas, he told his future wife, Carol, and needed a job in Winnipeg, where they would soon begin their adult lives.

“Why don’t you see if you could operate a streetcar?” she suggested in the spring of 1954.

He listened to her, and before he died in December, at the age of 93, Darragh was believed to be the last living operator of a Winnipeg streetcar, one of the only people left on earth who could say what it felt like to open the doors to passengers waiting at Portage and Main. If he wasn’t the last, he was one of the final few.

Darragh remembered being a four-year-old boy, in 1932, an only child accompanying his mother on the Portage Avenue streetcar to Eaton’s, where — if he was on his best behaviour — he would be rewarded with a 10-cent toy from Woolworth’s. He remembered the clang and the whoosh and the rattle of the cars, and the feeling that he could go anywhere. He didn’t ride the streetcar for long: in 1933, his father, a northern Irish immigrant, couldn’t find steady work, and the family of “city slickers” moved to Keyes, where they tried their hand at farming. The Darraghs had no radio for three years, no car for seven, no telephone for 10, and no electricity for 16.

Their roof leaked like a sieve every time it rained. With a few neighbours, the Darraghs tore their house down to build a new one from the old one’s lumber. For six months, they lived in a 14’ by 14’ tent as the new home was built. There were no streetcars in Keyes, but in a way only children can, Darragh never forgot his childhood rides downtown, and the streetcar sweetened in his memory as he grew up in its absence.

Carol’s suggestion was perfect: streetcar operators stood for a living, and they not only did it outside, but they did it in constant motion, standing still while moving forward. He got himself an interview, and it so happened the Winnipeg electric streetcar company was looking to hire 80 operators that month. Only 20 were trained to operate the soon-to-be-retired streetcars, and the 25-year-old Darragh was one of them. He went through three days of training, tagging along with experienced motormen and operators to learn the ropes, including to not touch the 600-volt wire running above the car, a lesson instructor Charlie Hays threw in almost as an afterthought at the station at the North Car House on Luxton Avenue at Main Street.

On April 19, 1954, at about 5:20 p.m., Darragh got behind the wheel of the streetcar for a seven-hour shift, wearing Badge #825 (The higher the number, the more junior a driver was). The previous operator stepped out of the car, gave the young man a few words of advice, and then was gone, leaving Darragh alone to punch a fresh book of transfers and adjust his mirrors before doing what he signed up to do.

On April 19, 1954, at about 5:20 p.m., Darragh got behind the wheel of the streetcar for a seven-hour shift, wearing Badge #825.

‘Turning around and facing the rear of the car I had about 30 passengers,” Darragh wrote in The Streetcars of Winnipeg: Our Forgotten Heritage, an informative, entertaining memoir of Darragh’s life and the streetcar’s era, published in 2015. “Some of them were reading the paper, a few were talking to their seatmates, and others were just looking out the window thinking about their day.

“Then I looked at myself in the mirror. Here I was a farm boy, only three weeks in the city and the only thing I had ever driven before besides a team of horses was a 1928 Model A Ford, a 1947 Ford, and a John Deere tractor,” he wrote. “I was in charge of a streetcar worth several thousand dollars, and more than that, I had all these people’s lives in my hands and they don’t even seem concerned! I looked down and thought to myself — How did I end up here?”

For 17 months, Darragh climbed aboard the city’s streetcars, driving every route available, clutching his 21-jewel Balco pocketwatch to keep on time, earning $1.30 per hour to not just drive the car but to feed the stove that heated it during the winter.

He drove women carrying live chickens, men in natty suits, lawyers, doctors, florists, children, and the elderly. All types of people rode the streetcar. It had been that way since 1892, when the first one started running along what is now River Road. The streetcar’s existence was key to that of the city: the Eaton’s department store was built in 1905 at Portage Avenue and Donald Street because the streetcar ran there. “These buildings would have never been built there if the streetcars hadn’t been there to give them service,” Darragh would say. The city expanded by, for and around the streetcar’s tracks, a vehicle for urban development.

“He was so enthralled,” says his daughter, Charlene Shatsky. “He was seeing history, and he was living it.”

“He was so enthralled. He was seeing history, and he was living it.” – Charlene Shatsky, Darragh’s daughter

But Darragh started driving at an inopportune time for a man who’d found his calling. In 1946, the Winnipeg Electric Streetcar Company carried 106 million passengers, but by the mid-1950s, the city was changing. After a wartime stoppage on automobile production, manufacturing was in full swing, and loyal transit passengers abandoned the streetcars for cars of their own. Meanwhile, the city was looking toward diesel busses. The same thing was happening all across North America, Darragh wrote. The end of the line was nearing, and it came in September 1955, when Leonard Kolley pulled the last revenue streetcar into the North Car House at 2:45 a.m.

The next day, a procession of streetcars chugged down Portage Avenue, eastward from the old racegrounds at Polo Park. When they reached the Bay, Darragh wrote, police blocked off all traffic as the cars proceeded to Portage and Main. There was Car #374, driven by Francis Daly, one of three remaining female operators. The next was the double-truck sweeper, used to clear the tracks of snow, driven by McGuire Cummings. Then there was #798, driven by superintendent Bill Jones. Each vehicle was built in Winnipeg and carried city and transit dignitaries, Darragh remembered. The streets were flooded with people waving goodbye. The chair of the transit commission, mayor George Sharpe, and each of the 12 reeves lifted a section of the track to signify the beginning of one era, and the end of another.

“Then #374, with its painted-on tears on the front windows, lurched forward. A quiet hush fell over the assembled gathering as they watched the four cars go around the corner of Portage and Main and head north out of view,” Darragh recalled in writing 60 years later. “Some of the several thousand people who witnessed these proceedings shed a few real tears for the great service the streetcars had given over their 73 years.”

The pain of losing the streetcar was still palpable, even after nearly six decades. “The buses are all the same,” Darragh says in Jeff McKay and Beth Azore’s 2010 documentary Backtracks: The Story of Winnipeg’s Streetcars. “I mean sure, they’re different shapes, but they’re all the same. The streetcars were individuals. I know you’re going to laugh, but they had a soul.”

“The streetcars were individuals. I know you’re going to laugh, but they had a soul.” – Brian Darragh

For 38 years after last boarding a streetcar, Darragh drove the very vehicle that replaced his favourite mode of transport. In 38 years, he only had one “blame” incident, and never hit another vehicle. For every five years with no chargeable or preventable accidents, drivers were entitled to claim one of six bonus prizes: a travel clock, a pen and pencil set, a flashlight, a Transit belt, a tote bag, or a sleeveless sweater. Darragh collected all six, and was named the Transit driver of the year in 1988, four years before his last shift in 1992, putting a close to a career in which his badge number fell from #825 to #1. He drove an estimated 900,000 miles.

But those 17 months driving a streetcar defined him. He became one of the city’s most knowledgeable sources of streetcar history, providing insight academics or younger transit historians could never have conveyed in presentations for schools and community groups. “He was a living history book,” says Azore. He saw the removal of the streetcar as a moment that split the city into two eras.

From the day the streetcars stopped, and especially in his last 30 years of life, Darragh made it his mission — along with other enthusiasts, historians, and a dwindling number of operators — to ensure the streetcar not be forgotten. Most were destroyed or scrapped. One car, Streetcar #356, built in 1909 in Winnipeg, sits in storage at the soon-to-close Winnipeg Railway Museum.

A committee to restore the streetcar has tried to raise the funds necessary to refurbish it for the better part of two decades, says Heritage Winnipeg executive director Cindy Tugwell. Throughout his memoir, Darragh, who sat on the committee, worries about what that means for the city. He begs readers to consider supporting the project before the streetcar rots away. The book opens with a call to action. “It’s Winnipeg’s 150th anniversary in 2023. How about getting Streetcar #356 on track then?”

“In the year 2014, it will be almost 60 years since the last streetcar operated,” he wrote. “By another seven years, you won’t be able to talk to a former Transit employee who operated one.” His sense of time was as precise as his Balco pocket watch: both he and his beloved wife died in 2021.

Before ending the book, he took himself on one more streetcar ride, vividly describing something most can only imagine.

“Personally, I’d be perfectly happy to be back on the old streetcar again, watching down the track on a frosty winter morning, hearing the groan and whine of the motors as the car picks up speed from its last stop,” he wrote. “You can hear it first, and then you see it in the distance sporting that bright orange front that can be mistaken for a furniture truck.

“As it comes closer you see the trolley sparks as it hits the overhead contacts and occasional switches. Pulling into the stop, the operator fans the brakes a couple of times and you hear the hiss of the air and can see it mixing with the early morning frost.”

He went on, recalling each hiss and clatter and gong as though he heard them the day before.

“Whoops, we are not living in that world anymore — it’s back to reality,” he wrote to finish. “Maybe someday, if I live long enough, they will restore #356 and we could have a similar ride in it. Like our youngest grandson used to say, ‘Bring it on!’ Hey, I’d settle for that any day. As I, too, am reaching the end of the line, I couldn’t have said it any better myself.”

ben.waldman@winnipegfreepress.com

Ben Waldman covers a little bit of everything for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Thursday, January 20, 2022 9:20 AM CST: Corrects reference to Donald Street