Folks of a feather flock together Growing number of Manitoba pigeon-racing enthusiasts revive centuries-old pursuit

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 10/12/2021 (1460 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

1. There They Were

The whistle to end the soccer match had just been blown one afternoon in 1982 when a 16-year-old boy looked up at the sky and saw them for the first time.

As his teammates left for the nearby mall, Bill Voulgaris headed in the opposite direction, mesmerized by an unexpected eddy of red, white and grey hovering above the backyard of the house on Cambridge Street, just across the way.

He crossed the street, drawn nearer and nearer, as if a magnet was pulling him. First, he had seen them, then as he got closer, he heard them, their velveteen coos humming like the engines of 100 feathered airplanes.

Voulgaris was no stranger to animals. He’d had some dogs and rabbits and budgies, and even a few fancy pigeons, birds bred more to show than to tell, their expressive plumage unhelpful when it came to aerodynamics. But these pigeons seemed different, the ones above the yard. They had wide, muscular chests. Their wings were supple, hardly a feather out of place. They looked nothing like city pigeons, neither rotund nor scruffy. These birds were fit. These birds were not quite pets and they were not quite wildlife. They were their own separate entity, somewhere in the middle, and in their two-storey River Heights loft, they lived like avian kings and queens.

Amid the flock, there stood a man unfazed by the birds’ movement. He looked to be in his 60s, but had a youthful energy when surrounded by the birds. He treated them more like peers than subordinates. He was coaching them, from the looks of it, noting the way they moved, which bird was fast and which bird was slow.

The man noticed the observer, and signalled him to come closer.

“He told me they’re racing pigeons,” Voulgaris recalls almost 40 years after finding the home that changed his life. “You take them hundreds of miles away, and they come back in hours.”

The old man’s name was Omer Van Walleghem.

2. Blood Lines

This is a story about pigeons. But it is also a story of navigation, a story of man and bird, feathers and fathers, of those who can fly and of those who never will. It is a story of lineage and a story of home. Of often misunderstood creatures, told in bloodlines.

Omer Van Walleghem’s bloodline went back, way back, to 1450, when his great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great grandfather Antheunis was born in a town called Wingene, in the country of Flanders, in the northwest corner of Belgium. The oldest form of the surname translates to “the place where they live together.”

For more than 400 years, that place was Flanders. Until 1892. Work was scarce on the family farm. So Omer’s grandparents, Ludovicus and Nathalie, rustled up $100 and sent two of their nine children across the Atlantic on a steamship. Adolphe and Camiel Van Walleghem were on the cusp of adulthood, 18 and 20 years old, when they arrived in Halifax, after three weeks and 5,000 kilometres. They hopped onto a train and headed further west. Three days later, they arrived in Winnipeg.

In their new home, they did what their ancestors did: worked on a dairy farm. They saved and saved, and by 1896 had saved enough to buy 160 acres in Ile-des-Chenes. Some would say they had it made, but the call of the Gold Rush came, and the brothers answered. In 1901, they returned, and with his nuggets, Adolphe returned to Belgium, where he met Elodie Anseeuw, who would become his wife and Omer’s mother. Once again, Adolphe boarded a steamship across the Atlantic, this time a married man.

For a few years, he ran a dairy in Transcona. But in 1904, a choice parcel came up for sale in a then-barren area known today as River Heights, at Ebby Avenue and Cambridge Street. Upon that land they built two dairies, Royal and Winnipeg. Business was strong, the family was growing, and Adolphe returned to Belgium with Elodie for a four-month trip in 1914. The next time he boarded a transatlantic steamship bound for Canada, Adolphe carried with him a renewed passion for something he left behind when he had first left Wingene: the sport of pigeon racing.

● ● ●

In Belgium, pigeon racing was a national obsession.

The sport started in the country in the 19th century, and Belgian fanciers were fascinated by what these little balls of feather and muscle could accomplish. The pigeons defied logic, expectation and mortal understandings of distance, speed and time. It seemed impossible: they could find their way back to their loft from places they’d never been. They could reorient themselves in the sky to find paths in the air where none appeared to be lain. They could fly hundreds of miles in a single day, speeding nearly 160 miles per hour.

By the end of the century, the hobby with one starting line and 1,000 finish lines was the national pastime. Fanciers started developing pedigrees of pigeons, thoroughbreds of the sky. They would buy fast, strong birds and cross them with their best pigeons, hoping to establish a lasting dynasty. Fantasy sports before fantasy sports.

In Winnipeg, pigeon racing was no hockey, but waves of immigration from Europe spurred by the First World War meant a community of fanciers was burgeoning, composed of settlers from France, Belgium, Britain, Poland and Germany. Newcomers from different worlds found commonality on the flatland in animals that thrived above it: a pigeon coos the same in Bruges as it does in Oxford.

Still, the men — it was usually men — who kept pigeons tended also to keep to themselves: clubs composed mostly of Belgians or Frenchmen started in Norwood and St. Boniface, headquartered at the Club Belge on Provencher Avenue, while in Elmwood and the North End, the Brits had clubs of their own. Behind their houses, they erected peculiar buildings, not quite garages but not quite homes: go for a walk down the back lanes of St. Boniface, and you will see them. Once, they were everywhere. Now, they stick out jagged like broken thumbs.

“No, I don’t use it for pigeons,” says a resident of Edgewood Street, whose parents bought the house he lives in, loft included, in 1959, “I use it for storage. What am I? A kook? What am I? Crazy?”

Most people have trouble believing pigeon racers exist now. They respond like this man, who questions the pigeon mens’ sanity. But 80 or 90 years ago, there were more than 900 fliers in Winnipeg, and in 1920, Adolphe Van Walleghem aspired to be one of them. All he needed were the birds, and he got them: pigeons from the famed Logan line, bought off a local Englishman named Bert Scarth.

On race days, Adolphe put his pigeons in crates and towed them on horseback from Cambridge Street to the Belgian Club. His birds did fine, but in 1926, they began doing finer: his nephew brought him six pigeons from Belgium, and after breeding, the offspring turned out to be some of the greatest pigeons in the country.

In a 600-kilometre race from Moose Jaw, Sask., birds No. 180 and No. 858 came in first and second. Omer helped his dad clock the birds in. Two weeks later, the birds flew out of Swift Current, Sask., at 6 a.m., Adolphe expected them home by five o’clock. At four, he was driving the cows into the barn when he looked up to the sky in the west.

Two specks. Closer, closer, closer. Adolphe climbed the fence to run back to the loft to see if his eyes betrayed him. There they were, No. 180 and No. 858, an hour early, the fastest pigeons in Winnipeg.

That year was 1930, and Adolphe Van Walleghem built himself a brand-new pigeon loft.

3. Still Standing

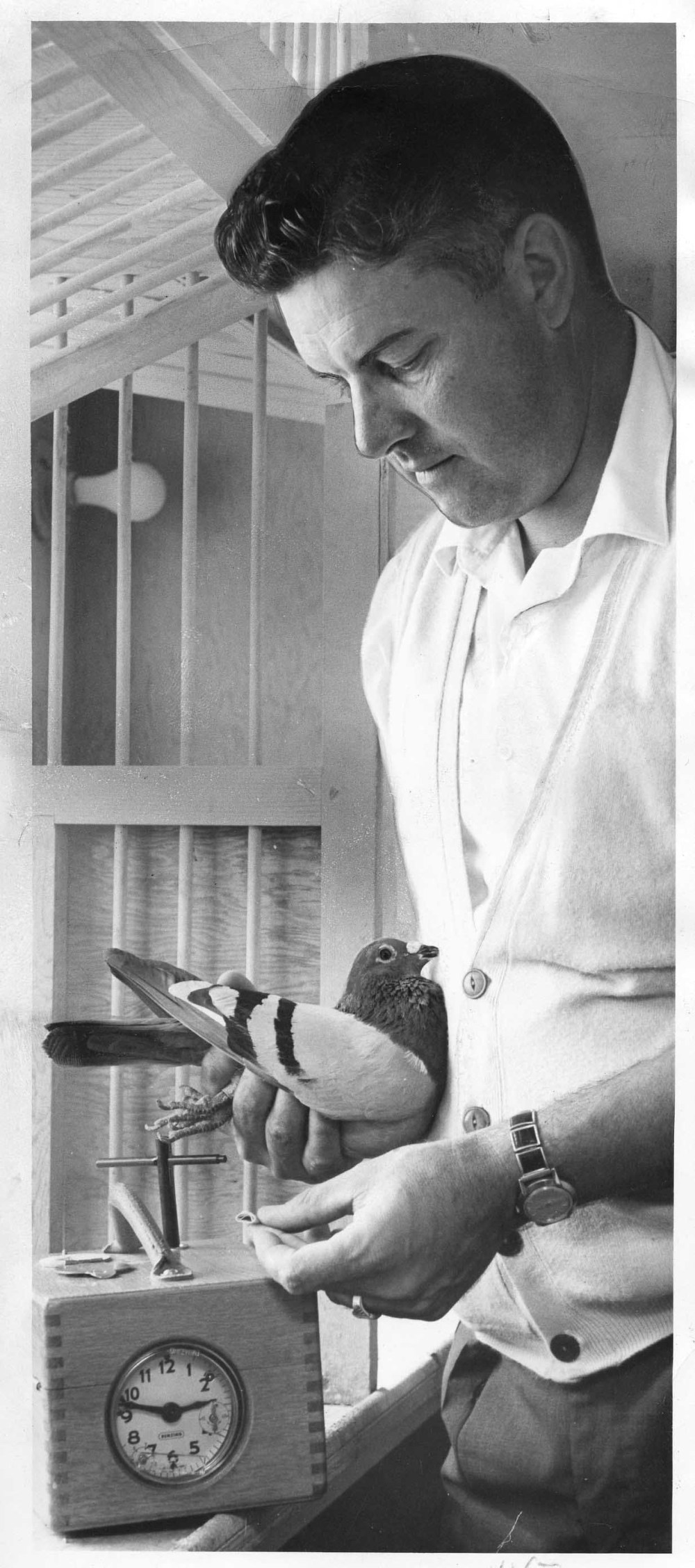

It’s 2021, and Ken Van Walleghem — Adolphe’s grandson and Omer’s son — is standing on the second-storey of that very same loft, with a newborn pigeon resting in his hands.

It looks like an alien: yellow strands, like straw, surround its head. White chest hair curls around its breast. Its beak is an embryonic pink. The bird is cute in an grotesque way, and grotesque in a cute way, but in Ken’s eyes, it is more: he looks at that little pigeon like it’s a miracle. He sees it for what it is and what it will be: a beautiful creature that can make grown men feel like children again. “I didn’t dream of flying,” he is fond of saying. “I dream of being a pigeon.”

Standing with Ken is Bill Voulgaris, who never left after showing up one afternoon in 1982 and meeting Omer Van Walleghem, who reached into his own loft and gave the 16-year-old a dozen pigeons with which to start his. It wasn’t without failure: Voulgaris twice came to his loft to find blood everywhere; weasels and raccoons are vicious creatures.

The two men have been racing partners since 1990. They learned just about everything they know about pigeons from Omer, who developed a legendary reputation for his training regimen. He was called by some the Godfather of Pigeon Racing, always generous with his time and knowledge, and gave away untold hundreds of birds to new fliers.

He always looked for an edge. After Adolphe died in 1938, Omer bought the family dairy with his brother Wilbur, and started raising children with his wife, Marguerite, while expanding the business to unforeseen highs. Still, he found time to manage his fantasy pigeon team, searching for new recruits to strengthen his pedigree. In the 1950s, Omer acquired two eggs from Belgium, which were then smuggled to Winnipeg inside a brassiere, according to some stories too whimsical to subject to fact-checking.

For 40 years, he worked alone, training the birds like soldiers. “It feels as if you’re holding feathers covering an abundance of muscle,” he told a racing newsletter in the 1980s. And a Van Walleghem bird’s condition must be peak, right down to their bowel movements, he said.

“Unless they show real good, they do not make it to the widowhood loft next year. My neighbour makes soup with them.” – Omer Van Walleghem in a 1980s newsletter

The wattles on their beak must be snow white. Their eyes must be bright, sparking and clear. The feathers must be tight and covered with white bloom. Their feet should be red and warm. They mustn’t overeat. A widower in good condition the night before a race will feel like a blown-up ball. They must be tame. The droppings should be small and firm. “They roll like peas in the morning. They are in a small pile with a few down feathers around,” he told the newsletter.

He was also a tough critic: “Unless they show real good, they do not make it to the widowhood loft next year. My neighbour makes soup with them,” he said.

When Omer got older, Ken joined him as a racing partner. They did everything together: the feeding, the training, the cleaning. When Omer reached his 70s, Voulgaris joined the loft. The three of them became inseparable. Voulgaris would arrive to pick up the birds for training at 4:30 a.m., and there was Omer, with a cup of coffee and a slice of toast for Bill. When his kids bought him a cellphone in the 1990s, Omer’s first thought was that Ken and Bill could call him with updates from those early morning training runs.

Omer turned 80. Then he turned 90. But he never fell out of love with his birds. On racing days, he could no longer go up to the second floor of the loft to welcome his pigeons home. So he would sit on his back porch with a pencil in hand, marking down the return times, just like he did when he was a boy.

● ● ●

Every day, Ken wakes up in a bedroom with walls covered in portraits of great Van Walleghem pigeons, and racing trophies atop his dresser. For years, he took care of his parents in this house, helping them stay home until the end of their lives. He now lives alone, but not by himself.

He goes out each morning to the loft his grandfather built to see his pigeons. He refreshes the water, he scrapes up the droppings, he sweeps the floor. Ken is in his 60s now. Tall, strong. Thick head of grey and black hair, the same as his favourite type of pigeons, the grizzles. He’s charming. Makes you feel at peace. Looks a bit like Bobby Orr. He used to fall asleep in the loft with the birds all around him when he was a boy. He’d play them songs on the radio. He still does that.

A picture of his dad smiles at him on the main floor. On the second storey, Omer’s handwriting is still legible on the walls. Every bird in the loft has their place: if they aren’t moving around, bobbing and waddling, they sit on shelves like trophies. The loft is cleaner than most apartments. Inside, the smell is hardly noticeable, a hint of anise leaves it smelling like black licorice. Outside, the smell is non-existent. There’s an almost imperceptible hum. Were it not for the birds, this might be just another shed. Instead, it’s another world.

During racing and training season, which runs May through October, Bill usually stops by early in the morning before work. He is bookish, particular, incredibly knowledgeable about the history of pigeon racing, and like Ken, deceptively youthful looking. He explains concepts about pigeon racing with detail one can only glean from a lifetime of study. He can pick up a bird, look at its feathers and decide whether it should fly, like a carnival sideshow character who can guess patrons’ weights. He looks intensely into the pigeons’ eyes as if he believes the birds understand him too.

He and Ken train the birds for their flights, taking them ever further to toss them and build up their endurance for the season’s longest races, which span as much as 700 kilometres. Bill and Ken rarely go more than a day without seeing or speaking to one another: they shop for groceries together, talk about sports, about Ken’s parents — whom Bill treated with the same respect as his own. Whatever Ken doesn’t remember, Bill does, and whatever Bill never knew, Ken has ready at the tip of his tongue.

“He and I are like brothers,” says Bill, now in his mid-50s. The two impossibly kind men might as well be.

They show off the newborn pigeon. That pigeon is here because of the first pigeons almost 100 years earlier: they can trace some of their birds’ pedigrees back all the way to 1930. They look at pigeons the way the rest of the world looks at humans. “He looks just like his dad,” Bill says of one of their best breeders. “That’s his son,” Ken says about another.

Pigeon racing is a sport of inheritance. Bill and Ken are following the footsteps of Omer and Adolphe, walking through the same loft door, sweeping and scraping the same floors. They don’t make pigeon soup. They don’t drive a horse and buggy. But most of what they do in 2021 is not far from what was done in 1921.

There is a problem, however. Most people these days would not think to construct a loft. City bylaws make it hard, and neighbours can make it harder: one member’s neighbour once took him to city hall, alleging the man’s pigeons were responsible for the spatter of bird feces on windows right underneath that neighbour’s birdfeeders. “How did he know it wasn’t the sparrows that pooped?” another racer reasonably asked.

If new homeowners find an old loft in their backyard, they’d likely tear it down to make way for a garage. (Kristen Feniuk, 26, turned the loft behind her St. Boniface rental into an enviable hangout space with her roommates after she swept away the feathers.) Most 16 year olds in Winnipeg would not consider pigeon racing as a hobby, if — and it’s a big if — they knew it was a hobby at all. Neither Bill nor Ken have children to pass the sport on to. They don’t want this tradition to die when they’re gone.

In the 1930s and 1940s, there were anywhere from 500 to 900 fliers in the city. But for years, membership of Winnipeg Pigeon Flyers Inc. hovered around 20.

Now it’s climbing back up. A new lineage is starting.

4. New Blood

Henry Salazar rolls up to the house on Cambridge Street, carrying two crates that coo. “Como estas?” he asks Ken, who smiles politely. It’s a Friday in September, which means the garage and driveway are about to get busy: it’s crating day, and Salazar — one of the club’s newest members — is among the first to arrive.

He has always loved pigeons. Loves animals, period. Back in Colombia, he loved them so much he became a veterinarian. On the open third floor of his house in Bogota, 200 pigeons flapped their wings. But in 2007, he left and ended up in Manitoba. His pigeons didn’t join him.

For more than a decade, he thought about his birds. Some people want a bigger yard so they can host barbecues. Salazar wanted a bigger yard so he could build a loft. Finally, a few years ago, he bought a larger property, in La Broquerie, an hour southeast of Winnipeg. He promptly found Voulgaris’s phone number and gave the president of the Winnipeg Pigeon Fliers Inc. a ring in December 2019. The following May, as the pandemic began, Salazar joined, and found refuge from his two jobs as a personal-care worker in six baby birds Bill and Ken gave him. Six have since become 70.

Every Friday during racing season, Salazar drives to Cambridge Street. It’s the highlight of his week.

More new blood arrives. “Mr. Ken, how are you doing?” asks Brix Delcarmen, 21, followed closely by his brother Brando and their friend, El-Deeb Essa, 17, who looks after the birds at the Delcarmen loft while the brothers work at a mink farm. In a little over a year since joining, Brix has become one of the most promising fliers in the city.

“This guy is a champion,” Salazar says, shortly before lighting up a cigar. “He is,” Brix replies with a laugh.

Suddenly, the driveway is packed with men and their birds: There’s Cornelius Martens. Dick Van Walleghem walks over from next door. Tony Poetker, John Olfert and Billy Cabrera congregate in the garage as Bill registers their birds, whose ankles are scanned electronically to enter the race. Robert Madlangsakay arrives. Robert Hernandez follows. Johnsen Arrogancia, Mar Cacho and Red Opina pull up. Ivan, Angelo and Alan Reyes, too. They caress the birds gently before putting them into the trailer that will carry them to Dryden and Ignace in Ontario, 350 and 450 kilometres away, respectively.

A century after pigeon racing arrived on the Prairies, a bloodline of new Manitobans is keeping the sport alive. In the last three years, 13 members have joined the club.

No matter where they’re from, the members share a mutual love. They talk about their pigeons like they’re their children, and they talk about their pigeons like they themselves are children again.

“We protect them from whatever calamities come their way,” says Brix.

“Once they’re flying, I become a child again. Nothing else matters,” says Mar Cacho.

● ● ●

Joe Belchior has been around the birds for most of his life. As a boy in Portugal, on the Azores Islands, every house had pigeons, but not for sport. “They raised the birds for meat,” he says. But Belchior wasn’t hungry. He fell for the pigeons, in particular a checkered-pied.

“When we moved to Winnipeg (in 1975) I wanted to bring him with me,” he says in his loft in Woodlands, an hour northwest of Winnipeg.

His family settled on Furby Street, and 11-year-old Belchior went for a walk down the back alley, where he saw the pigeons. Instead of shooing him away, the homeowner waved him over. “That was a long, long time ago,” recalls Jurgen Bonus.

Bonus gave the young boy, who knew little English, his first birds, and as he grew up, Belchior would accompany him to local pigeon shows to meet fanciers from across the province. In the birds, Belchior found a community. But it didn’t last, Belchior says with regret. He started drinking. It got bad. He couldn’t take care of the pigeons anymore, so he sold them. For the first time in years, he was birdless and aimless.

Until the winter of 2001. Some pigeons were up for sale, and after Belchior bought them, he no longer had time to go out and drink. “I spent all my time with the birds,” he says. “They helped me get sober. They helped me stay sober.” It’s 20 years, this coming February. Belchior, in his late 50s, looks no older than 45. The birds keep him young.

“Pigeons are just like us. They care for each other. They love their babies. They’re protective. They’re smart. They’re peaceful. I can sit there and just watch ‘em.” – Joe Belchior

Each morning, Belchior wakes up at 4 a.m. He hugs his three foster kids and his wife. Then, he goes to his loft. He gives the birds food and water. He gives them apple cider vinegar and garlic. “Same thing I drink,” he says. His birds looked so damn good, so healthy, that he had to give it a try. “My back used to hurt me. Six months drinking that, it felt great.”

“Pigeons are just like us,” he says, holding a checkered-pied. “They care for each other. They love their babies. They’re protective. They’re smart. They’re peaceful. I can sit there and just watch ‘em. I know who trusts me and who doesn’t. That feeling you get when a bird jumps up and sits on your leg. It’s magical to me.”

Other men use that word — magical. The cooing is tranquil to them. They start their days outside, bright and early. They don’t check their email; they check their pigeons. In keeping their birds, they keep themselves. The routine becomes ritual, which becomes medicine.

Belchior and these other men must know something the rest of us don’t. They make you reconsider things and people you may have dismissed. They recognize genius in pigeons, some of the city’s most maligned and unappreciated creatures. They see athletes and confidants where many would see annoyances. They find comfort within the confines of a pigeon coop. They make you ask yourself: who is odder — the man who feeds the pigeons on the sidewalk or the one who shoos the birds away?

One more question they make you ask yourself: how on earth do these pigeons find their way home?

5. The mystery is the romance

It’s a question Charlie Walcott has been asking himself for almost 60 years.

He was working at Harvard University in 1965, as an assistant professor of applied biology, when a graduate student approached with a conundrum. The student wanted to track seagull flight using radio transmitters, but was having problems. The birds flew out of range, and they got distracted by snacks at the nearest dump. Walcott suggested homing pigeons instead: they wouldn’t get lost.

To follow the signal, Walcott got his pilot’s licence. He was surprised to find himself spending thousands of hours chasing pigeons. As a boy in Cambridge, Mass., he mocked his father’s love for birds. But that first day in the sky set the young scientist on a new path: his father lived long enough to see his son become the director of Cornell University’s Lab of Ornithology; Walcott is now professor emeritus of neurobiology and behaviour there.

In the 1960s and 1970s, homing was a burning question. Scientists in Italy, Germany, Poland, and the U.S., conducted elegant experiments to answer it. In Italy, researchers focused on smell. At the State University of New York at Stony Brook, Walcott researched how pigeons use the earth’s magnetic field, while at Cornell, in Ithica, N.Y., a scientist named Bill Keeton ran myriad studies with a loft of more than 2,000 pigeons. (There is a connection to Winnipeg: Keeton’s pigeon keeper was a relative of the Van Walleghems named Andre “Andy” Gobert; his father brought Adolphe Van Walleghem those eggs in 1926).

At 87, Walcott is asked whether there is a clear answer as to how pigeons find their way home.

“I would say we don’t know. That’s the short answer,” he says over Zoom from his office at Cornell. “Here is a longer one.” He clears his throat and talks for eight minutes.

“If you’re a pigeon, and you’ve been taken some place you’ve never been before, the first thing you gotta do is figure out is what direction it is from home. Did they take me north, south, east, west? That’s what we call the map problem. It’s simply, “Where am I?” Once they solve that problem, they employ compasses.”

“I would say we don’t know. That’s the short answer.” – Charlie Walcott

One, Walcott says, is the sun. Nobody disputes that. But what if, gesturing to a dark cloud outside his window, the sun is covered? Then, pigeons need a secondary compass, and that is believed to be the earth’s magnetic field. “The problem then becomes that map,” Walcott says. But there’s no consensus on how the map is built.

Some believe in what Walcott calls the stink theory, or the olfactory navigation hypothesis, proposed by the Italians in the 1970s: pigeons use an odour-based map to find their way home. Others believe magnetic fields play a significant role in homing, or that low-frequency hearing does. John B. Phillips, a professor of biological sciences at Virginia Tech University, who worked in Keeton’s lab in the 1970s, says the only thing people agree on is that there is not a definitive answer to the homing question: support and confounding results exist for every pathway thus far proposed.

“We have all of the pieces of the puzzle,” Phillips says. “The problem with the birds is there are 17 different ways these guys can put together these components of the navigation system to solve the (map) problem of getting home.” Some scientists, he says, avoid replicating experiments that might disprove favoured hypothesis, leaving the answer ambiguous, at best.

“The problem with the birds is there are 17 different ways these guys can put together these components of the navigation system to solve the (map) problem of getting home.” – John B. Phillips

“We don’t know,” Walcott repeats. “If you grow up in New York City, I bet you’d use the roads to find your way home. They’re all nicely rectilinear. But here in Ithaca, you’d be hopeless if you tried that. You’d use the lake, or the clock tower. My point is I think pigeons are opportunists. They use whatever makes sense in their environment.” Different pigeons who grew up in different conditions may use different cues, he says, which may explain different research results. “It’s not just one of these things. It’s whatever is useful. Am I clear?”

We see them when they leave and we see them when they return. How they get from one point to the other is an unanswered riddle.

Bill Voulgaris for one doesn’t want to know.“It would ruin the romance.”

6. Last Race of the Season

Lilly Guo pulls into Ken’s driveway to do an important job: driving the pigeons to their release point, seven hours away in Thunder Bay, for the last race of the season.

For the past three years, she and her husband Richard have been pigeon chauffeurs every weekend during racing season. They make $100 or so for the short-distance races, about $300 or $400 for the long ones, but they don’t do it for the money. They do it to have a little bit of adventure and rekindle a connection to the past. In China, Richard had 30 pigeons growing up.

On this day, their six-year-old son Jeffrey begged to join his parents. They hooked up the trailer to their SUV and headed to Ontario. The trailer is light. Two weeks earlier, the fliers got a reminder that pigeons don’t always come back: dozens of birds took five or six days longer than expected to return from Ignace and Dryden. Wind, smoke or predators are possible explanations for the confusion. One bird was reported outside a town in Minnesota. Some still haven’t returned. The ones that did needed a break.

Richard drives at night, and when they arrive in Thunder Bay, the family sleeps in their vehicle, on a mattress they carved to fit inside. At 6 a.m., they wake up, and get ready for the release.

“When you watch them, you feel freedom.” – Lilly Guo

On the journey, the pigeons drink their water, they look out the little slits as the SUV rolls along. They sit there, patiently, waiting for the opportunity to go. When it comes — when the locking mechanism drops and the grate opens — they do not squander it: they leap — one by one and all at once — into the sky.

As the birds take off, Jeffrey can’t keep still. He bounces up and down, clapping, and the three chauffeurs stand there, watching as the birds slowly disappear from sight, knowing they will lose in the race back to Winnipeg. It’s a moment that never gets old, says Lilly.

“When you watch them, you feel freedom.”

● ● ●

Seven hundred kilometres away, Ivan Reyes waits patiently for his pigeons to come home to the family loft he runs with his dad Alan and uncle Angelo.

The Reyes Loft started in July, one of the club’s newest. But the Reyes aren’t new to this: all three were avid fliers back in the Philippines, where pigeon racing is incredibly popular.

This year, a few years after moving to Winnipeg, they acquired their first birds. Some from Van Walleghem and Voulgaris, who give away dozens of birds annually, and a few from Robert Hernandez, who sold Ivan a baby pigeon for $25 in July. Ivan, 24, named her Luna, and she was one of the birds on her way home from Thunder Bay. She was a young bird, untested, so Ivan expected her back around 6 p.m.

“Suddenly, I heard something,” he recalls. It was 5 p.m., and Luna was home. She placed in the Top 10.

“I don’t easily cry, but the feeling of pride overwhelmed me,” Ivan says. “No tears dropped from my eyes, but my uncle and dad, they were crying. We hugged, we jumped. We were all so happy. The performance of the bird was that beautiful.”

Ivan struggles to find the words. After a moment, he does. “Imagine you had a relative who moved away. You wait by the window for them to come back. You’re not sure when they will. And then you see them walking up the sidewalk,” he says. “That’s how I feel when a bird comes back.”

7. Until Next Season

The racing season is over. Snow has fallen. It’s late November, and the pigeons in the old loft on Cambridge Street have begun their moult. They’ve worked hard, and now they build new armour. Some will breed new youngsters in February. Until next season, they rest.

Bill Voulgaris reaches into a barrel of feed and sprinkles it onto a trough. The birds dig in. They surround him, but he’s unfazed by their movement, standing amid a flock of grey, white and red. The pigeons peck at bits of corn and seeds like fingers on a typewriter as deadline approaches.

Ken Van Walleghem leans against the wall, grinning. He looks at those birds and he sees beauty. In their coos, he hears music. He must know something most people don’t. “Nothing better than this,” he says to nobody in particular.

In this loft, he is home.

ben.waldman@winnipegfreepress.mb.ca

Ben Waldman covers a little bit of everything for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.