Prairie icon Etienne Gaboury's Précieux-Sang church fuses together modernist design and religious renewal

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 25/10/2021 (1506 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

On my way to visit l’ Eglise du Précieux-Sang in St. Boniface, I got lost. There was road construction, and I somehow missed my turn. I managed to find my way, though, when I glimpsed that distinctive spiralling roofline in the distance.

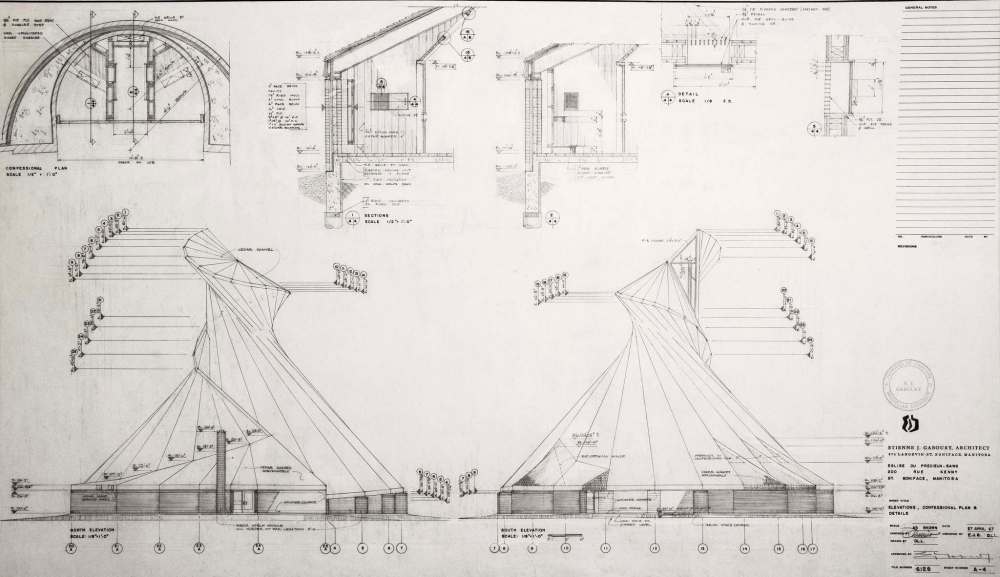

Etienne Gaboury is one of Manitoba’s most prominent architects, and Précieux-Sang is perhaps his most identifiable and iconic design. Firmly grounded in the earth by a low horizontal band of masonry but reaching to heaven with that wild, whirling wooden roof, the church is both expansive and intimate, bold and humble.

Phillipe Lessard, a member of the church’s administrative council who leads me on a building tour, remembers when the church was being constructed, from 1967 to 1968. “I was in Grade 9, across the street there, and I remember we kids were always looking out the window,” he recalls.

He admits his grades suffered that year as he was distracted by the building process. Lessard later studied architectural drafting, so clearly something stayed with him.

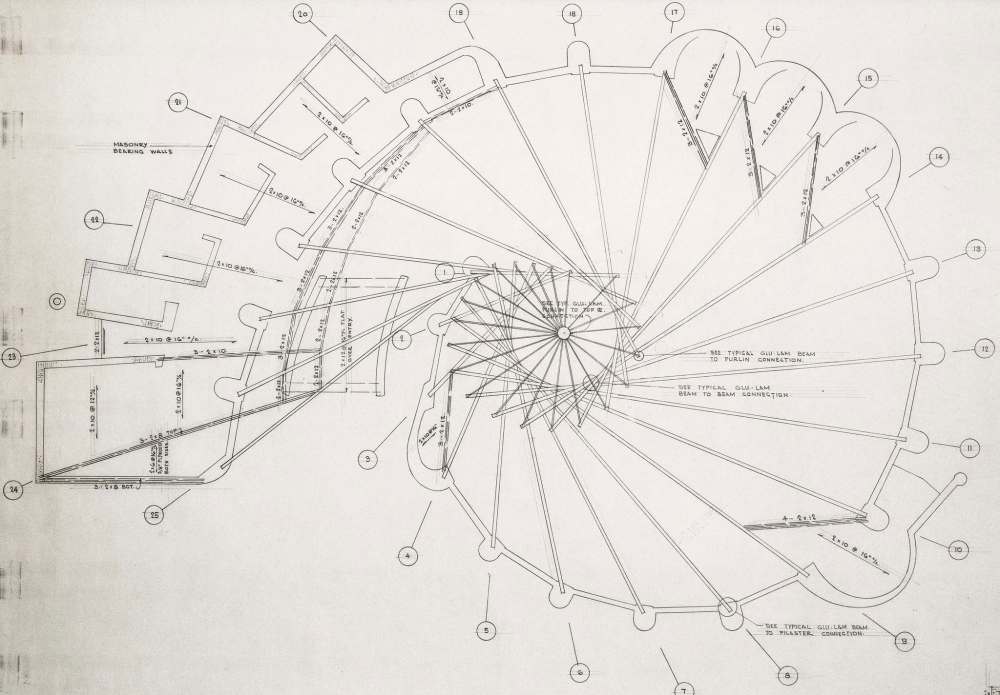

“Can you imagine building this structure?” he asks, pointing to the dramatic wooden lines of the central ceiling. “You needed two cranes, one to hold that beam, another crane to hold the other beam, while you interlace all the other ones on top of each other.”

In the 19th and early 20th century in North America, architects often relied on imposing scale, ornate fittings, precious materials and historical references to create a sense of awe and majesty within places of worship.

Précieux-Sang is part of a postwar wave of religious structures that came about as architects created sacred spaces using the more minimalist language of modernism. These buildings attempt to embody and express spiritual feeling through the subtle interactions of mass, void and light.

Within the Catholic church, these developments accelerated after the Second Vatican Council, which was conducted from 1962 to 1965. Vatican II made Catholic religious life more participatory, with the priest facing the congregation and conducting mass in the language of the parishioners rather than in Latin. This movement was accompanied by new provisions that officially allowed for more freedom in church architecture.

The main space of Précieux-Sang is circular and open, but the design quietly encourages a way of moving through the sanctuary, suggesting a form of spiritual journey as people draw closer to the altar that is set beneath the centre of the spiralling 29-metre ceiling. “The whole process of the church is that the congregation, as they are coming in, are on a journey to the promised land. They’re going toward heaven,” explains Lessard.

The design also emphasizes the communal aspects of worship, with simple, sturdy oak pews placed in a semi-circle around the altar. “The object is to have everyone around the altar, so it doesn’t matter where you sit, you’re always part of the ceremony,” according to Lessard. The floor slopes very subtly toward the altar, and the floor’s bricks are laid out to lead there as well.

By upbringing, experience, education and interests, Gaboury seems particularly suited to fuse together modernist design and religious renewal. Born in 1930, he grew up in a Franco-Manitoban Catholic family who farmed near Bruxelles. He later studied architecture at the University of Manitoba and then spent a year in France. As Faye Hellner points out in her essay on his work in Winnipeg Modern, an overview of our city’s modernist architecture, Gaboury was profoundly affected by Le Corbusier’s revolutionary Notre Dame du Haut chapel in eastern France, which put aside the traditional rules of church design to express the sacred through what Gaboury called “immeasurable form.”

In Précieux-Sang, light comes in from windows near the spiral’s peak. Even as you experience this light, you cannot directly see the source from below, so that the mysterious quality of illumination within the church becomes a moving metaphor for spiritual yearning. The spiral is also slanted and off-balance, so that it seems to be in constant, surging, upward motion, reminding congregants that faith is not a static quality but a dynamic process.

Many recent interpretations of Précieux-Sang see the church’s ceiling and its 25 supporting beams as a reference to — though not a literal copy of — the structure of a Plains tipi. Gaboury is distantly related to Louis Riel on his father’s side and has an Ojibwe great-grandmother on his mother’s side. He has suggested, in a 2015 interview with Indigenous architect David Fortin, that these connections weren’t much talked about when he was growing up. Gaboury sees layers of religious, cultural, social and personal factors, including his Métis heritage, that have affected his work, in particular his committed regionalism and his deep connection to the natural world.

Précieux-Sang may draw on aspects of international modernism, but it’s a prairie church. There are few windows, making the structure feel sheltered, perhaps as a response to the cold Winnipeg winters. The materials, including glazed bricks and cedar shakes, are modest and locally sourced, with a warm, organic feel and an earthy colour range. The level of unifying detail goes right down to the custom-built wooden door handles on the confessionals.

From these small things to that remarkable ceiling, the church uses simple elements to suggest something much more, what Gaboury has called “a mystical space, going up forever and ever.”

alison.gillmor@freepress.mb.ca

Landmarks

Landmarks is a monthly feature in which columnist Alison Gillmor explores unique and iconic Winnipeg buildings and locations.

Studying at the University of Winnipeg and later Toronto’s York University, Alison Gillmor planned to become an art historian. She ended up catching the journalism bug when she started as visual arts reviewer at the Winnipeg Free Press in 1992.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.