The pure heart and full life of Nihad Ademi

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 21/10/2021 (1509 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

He was a man who carried with him the quiet burden of survival. In the Omarska concentration camp, he had watched as hundreds of Bosniaks, Bosnian Croats and Muslims were starved, beaten or killed. Neighbours, friends, family members.

Nihad Ademi saw it all.

“I am a human being,” Ademi said in a short film about his life, shot a decade ago in his adopted hometown of Winnipeg. “And I learned that the hard way.”

Ademi, who died Sunday at 52, spent much of his life grappling with the question of what being human meant, and he did so in every medium he could access: in his photography; in G. Love, the magazine he self-published; in conversations about art and life over the counter at his daily Corydon Village haunt, Bar Italia; and perhaps most directly in his work as an actor and filmmaker, which saw him collaborate with the likes of Guy Maddin and composer Alexander Mickelthwate.

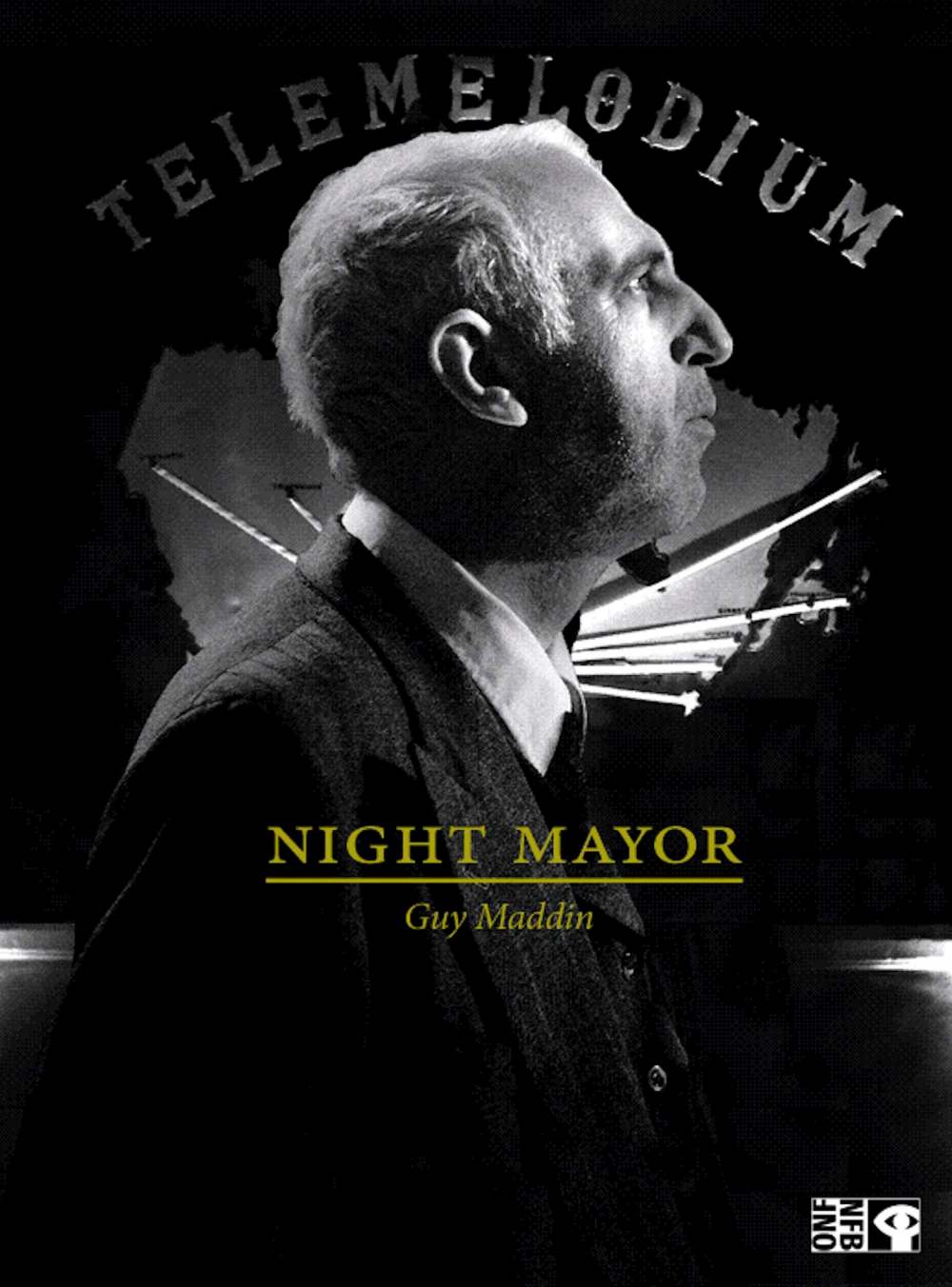

“Before I ever met him, I would see him at Bar I, and I saw him getting hugged by everyone. So many people showering affection on him. I wasn’t sure if he was a gangster demanding some sort of tributes from people, but when I finally met him, I was startled with how instantly I liked him,” says Maddin, who cast his new friend in the lead role of Night Mayor, a short film in which Ademi played a character who could translate music made by the Aurora Borealis into moving pictures.

“He approached the world like an artist, whatever that means. He was interested in observing things and retranslating them into a medium so other people could feel how he felt,” says Maddin. “He had friends who were in trouble and friends who weren’t, and he just had a way of sitting there, in the calm eye of a hurricane.”

Ademi was a central character, first in life and later in celluloid, both where he was from and where he wound up.

In his homeland, as a teenager, he was a masterful chess player, according to friends, and had an artistic spirit from an early age, along with an obvious, yet subtle intellect. But his life, along with those of millions of people in his region, was interrupted by the Bosnian War, which began in 1992 and was defined by tension, systemic massacres, ethnic cleansing, and political instability.

In his 20s, Ademi was held captive for 202 days in Omarska, which was later classified by global human rights organizations as a concentration camp, where crimes against humanity were perpetrated. In a span of three months in 1992, thousands of non-Serbs were corralled into the camp, with hundreds being killed and most survivors being deported or leaving the region as refugees.

Ademi and a younger brother wound up in Winnipeg, and struggled at first to adjust to the new land. An absence of threats on his life didn’t leave Ademi any less skeptical of the new people who surrounded him. Ademi once told the Free Press about an interfaith organization taking the brothers on weekly excursions.

“Every time they would come and take us in an Econo van I thought, ‘These guys are lying to us’,” he told former columnist Gordon Sinclair Jr. “I couldn’t trust nobody.” He would go to sit at the St. Vital shopping centre, watching people, trying to both remember what he had lost and what, suddenly, in a new country, he could seize again.

As time passed, though, he remained enigmatic, he started to open himself up to the possibilities of Winnipeg: he shot photos for the Winnipeg International Jazz Festival, volunteered with arts organizations and was quickly embraced by some of the city’s leading artistic lights, approaching every conversation as a chance to understand what it was to be human, and what it meant to create.

Many of those first conversations happened at Bar Italia, a Corydon area staple where many people from different places, not just Italy, gathered. “I guess he was looking for a good European espresso,” says manager Rhea Collison, who considered Ademi a close friend. Ademi seemed to attract affection, Collison says, and it was always clear how much he loved living, how little time he had for negative thought.

“If you were hungry, he’d give you half of his sandwich, without a moment’s thought,” she says. “That’s the kind of person he was.”

He was generous in conversation, which is how he soon found himself a fixture at the cafe. Maddin found him magnetic, and so did Mickelthwate, who related to Ademi’s perspective on art. “He became, really, my best friend,” says Mickelthwate, now the music director of the Oklahoma City Philharmonic.

Mickelthwate, like Maddin, wanted to give his friend as much generosity as he received from him: he scored his films, emceed their openings, and with Maddin and an endless community of “Nihad supporters” helped usher their friend’s debut film, White Balloon, to reality.

In the film, released in 2016, Ademi returns to Omarska to assess that chapter of his life and his people’s history. Ademi interviews concentration camp survivors, each of whom releases a white balloon marked with the name of someone who, unlike them, did not make it out alive.

In the film, as in most of Ademi’s art, he is brutally frank and unwilling to either polish out his rough spots or glorify his own experience: his brooding narration, powered by his deep voice and deliberate pronunciation, matches the pain on the screen. In a trailer for the film — a shockingly effective one that helped him raise the remaining funds needed to produce it — Ademi calls Omarska “the place where my life ends, begins and keeps going in circles.”

“Fear and sorrow are all that I’ve known,” he warbles. “They are my shelter and my home.”

Maddin knew his friend had an undeniable screen presence — his profile, his voice, his reflective eyes — but was taken aback by the way that translated into his work as a filmmaker. He’d neglected to speak much about his past, carrying it around like “a chunk of history” inside him. On screen, the depth of that history revealed itself, illustrating the scars of his people and his own survival.

“Once he decided he wanted to make films, I think he found that he himself was his best subject,” Maddin says. “When he made White Balloon, as a piece of therapy it was a raging success, but as a movie it provided an honest point of view of a staggering tragedy.”

Ademi’s film debuted at the Hotel Fort Garry, with 300 supporters and friends in the room to watch. The reception was emphatically positive, and Ademi was greeted with hugs and kisses. Later, the film screened at an international film festival in Milan, where it was nominated for best documentary short and where Ademi won a special award for education.

He later made movies about Mickelthwate and one about the Seven Sacred Teachings held by many Indigenous communities in Canada, using his empathetic eye to draw attention to the realities of colonization in his new home.

“For me, the loss of Nihad Ademi means the loss of Winnipeg’s most urgent, poetic and emotionally raw documentary filmmaker — a filmmaker who came to the practice late in life, and was really only getting started,” said Jonah Corne, a film professor at the University of Manitoba who called White Balloon a masterpiece. He described Ademi as the “most popular man who ever stepped foot on Corydon Avenue.”

“My favourite part of the movie is the non-stop stream of Nihad’s voice-over narration: his instantly recognizable, gravelly voice, speaking so humanely, with so much pain but with an impossible optimism,” Corne said.

Last year, during the pandemic, he returned home to Europe to help his mother, and at Bar Italia, he was given not one, but many goodbye gatherings. “In many ways, people got to say goodbye then, and that’s a wonderful thing to be able to do,” says Collison.

But earlier this year, he returned to Winnipeg, and walked back into his old haunt and his old life. While in Europe, he added to his extensive portfolio of still photography, a collection that Collison said could fill a museum. Dozens of those photos are displayed on the bar’s walls, illustrating Ademi’s approach to art: non-judgmental, observational, realistic in every sense of the word.

His death came suddenly, says Mickelthwate, who spoke with his friend two days earlier. He was at Bar Italia Sunday morning. “It was out of nowhere,” says Mickelthwate. “I am still numb.”

At the time of his passing, Ademi had just put the finishing touches on a book of poetry in the Bosnian language, which Mickelthwate describes as looking inward for personal reflections on a life well-lived, in spite and because of the universe.

“He would never think that he was as great at what he did as he was,” says Collison, who knew him for over 30 years. “He was the most humble person I’ve ever met.

“He lived and let live,” she adds. “He saw no value in negativity. I don’t think he could have been the artist or the person he was if he didn’t have that mantra.”

He was a human being. He was himself.

ben.waldman@freepress.mb.ca

Ben Waldman covers a little bit of everything for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.