Space: the ultra-exclusionary frontier Capt. Kirk takes one very expensive step for a man, in a giant cautionary tale for mankind

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/10/2021 (1516 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The first astronauts were test pilots. It seemed, at the time, to make the most sense. They were creatures of military habit, healthy and focused and a little shorter than average. They followed orders. They subjected themselves to an unending barrage of physical and psychological tests. They were, for the most part, serious men.

As they pursued the tasks set before them, it was easy to celebrate them as superhuman. They were, of course, no different than the rest of us, gifted but imperfect. Still, of all their gifts, the best they possessed was a combination of training and temperament that gave them a remarkable ability to stay calm while facing their own deaths.

By the late 1970s, as the space shuttle program began to ramp up in the U.S., the background of astronauts began to shift with it. The pilots were still there, but now there were also scientists, men and women who had devoted their lives to the pursuit of knowledge, and now offered to serve as science’s hands and minds above the sky.

They are heroes, all of them. They went all that way for us, and for us some of them gave their lives. The work they did, and still do, has enriched our understanding of everything from our place in the cosmos to how to treat cancers; the technology developed in pursuit of spaceflight’s goals has had innumerable terrestrial applications.

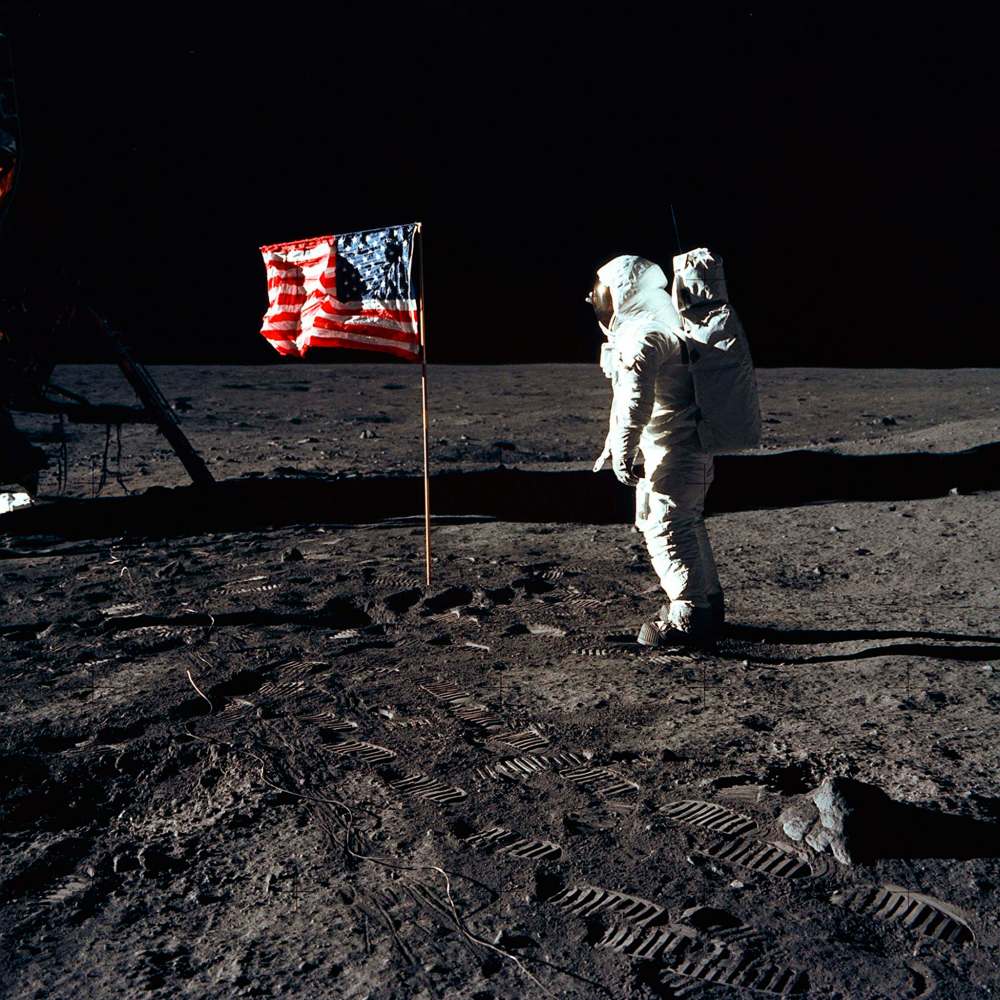

Yet space exploration no longer commands the sense of awe that it did when Neil Armstrong made his one small step, and the whole world tuned in. Back then, the effort was a sudden expansion in our entire concept of what is possible; what comes next, such as putting people on Mars, now feels more a march toward the inevitable.

Lately, though, people have been tuning back in. Because the type of astronaut we now watch leap off the Earth is changing again. The first generation were test pilots, the next were scientists. The new ones are just really rich.

In case you missed it, William Shatner went to space Wednesday, the Star Trek actor boldly going, at age 90, to a place where exactly 555 other people have gone before. It was a short flight, only 11 minutes, enough to kiss the Kármán line, 100 kilometres above sea level, that serves as the boundary between “down here” and “up there.”

At the moment he rose up, on Amazon billionaire Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin rocket, Shatner’s Twitter account issued a quote from Sir Isaac Newton: “I do not know what I may appear to the world, but to myself I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the seashore… whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.”

In being blasted up to the great ocean of undiscovered truth, Shatner joined a list of other notables who have gone to space on private flights in recent months, including Bezos, Virgin Group billionaire Richard Branson and the 18-year-old son of a wealthy Dutch financier.

Here, it should be noted that space tourism is not new. It has been tossed around since the 1980s, going through spates of ambitious plans and resistance; in the 2000s, a handful of trips to orbit were sold for about US$25 million apiece. But it is poised now to accelerate amidst a new era of commercialized spaceflight.

The debate around space tourism, and the commercialization of space more broadly, is longer than we have room for here. But it is now, more than ever, a topic commanding attention: on social media, supporters of Elon Musk’s or Bezos’s spacefaring ambitions have tangled with critics on the value, or lack thereof, of those efforts.

(After the Bezos flight, a local man on Twitter declared only “communists” oppose funding for spaceflight, forgetting, apparently, that not only did communists get to space first, but the Soviets achieved dozens of other firsts, including the first spacewalk and the first space station. Our road to the cosmos was paved by public investment.)

Yet it occurs to me that many of these debates dance around something that’s more difficult to quantify, something that’s hard even to name. It comes down to this: there is still a wonder in space, a sense of the sacred that can be profaned, when it is opened up as a tourist destination for the famous and the ultra-wealthy.

We live in a time where everything can be bought, for a price. If you want to be famous you can buy that, provided you have enough money to pay for a good publicist and little enough shame to care what you get famous for. You can buy beauty, or a chance to kill an endangered animal or admission to the most prestigious schools.

And you can even buy a trip to the summit of Mount Everest, if you want. Your own legs have to carry you there, but you can buy the guides and Sherpas to fix the ropes and set up your tent and ferry your gear up the mountain; or, in other words, you can pay for someone else to take the biggest risks of the expedition for you.

In that light, space was one of the last dreams that could not be bought. It had to be earned, and in that way, those who earned it, whether test pilots or scientists, also served as stand-ins for all the billions of us remaining on Earth. They were the best of us, living representations of our potential, of what ability can be unlocked in the human brain.

So what do we lose, when we offer it up as an experience that can be bought? In 2012, the philosopher Michael J. Sandel authored a book, What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets. In a related article for The Atlantic, Sandel homed in on the central questions about what we risk when more and more things can be sold.

“Putting a price on the good things in life can corrupt them.” – Michael J. Sandel, philosopher

“It is not about inequality and fairness but about the corrosive tendency of markets,” he wrote. “Putting a price on the good things in life can corrupt them. That’s because markets don’t only allocate goods; they express and promote certain attitudes toward the goods being exchanged…. Sometimes, market values crowd out nonmarket values worth caring about.”

Sandel made no mention of space in the piece; for examples, he cites how the moral refusal to treat certain things as commodities, such as votes or internal organs, reflects an insistence on valuing them in the right way. “Some of the good things in life are degraded if turned into commodities,” as he wrote; they are demeaned by the selling.

I would argue that access to space could be included in this, at least at the current stage of our development. It is possible that generations far in the future will move through space as regularly as we move across continents; but for now we ought deeply consider how offering it up to the rich will change what spacefaring means.

Over the years, many astronauts have spoken about finding something sacred in the journey, as viewed through the lens of their faith. On Apollo 8, the first crewed mission to reach the Moon’s orbit, astronaut Jim Lovell looked out the window and covered the shining blue gem of Earth with his thumb; it brokered a deepening of his Presbyterian faith.

“In reality, if you think about it, you go to heaven when you’re born,” he later said, of that experience.

But oh, what harm we have done to that heaven, as we have bought and sold nearly every inch, exploiting many of its wonders to benefit the whims of the rich. Maybe it’s inevitable that space will become the same way; but for now, as large as it lives in our dreams, there still ought to be a sanctity in who gets to venture out in our place.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.