The journey from farm to table Free Press writers and photographers travel hundreds of kilometres down highways and gravel roads in pursuit of 10 Manitoba ingredients to be showcased in a specially prepared fall supper

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 01/10/2021 (1620 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The seeds of this project were planted in February. Back when the ground was still frozen and Manitoba farmers were still blissfully unaware of the challenges and possibilities that lay ahead during this year’s growing season.

This project started with an out-of-the-blue message to Winnipeg chef Matty Neufeld asking if he would be interested in coming up with a fall-inspired dish made entirely of Manitoba ingredients — the journey of which a team of Free Press reporters would follow from seed to harvest. A farm-to-table story in the truest sense.

“I thought you had the wrong email,” Neufeld says with a laugh. “I was pretty excited and really honoured to be part of this.”

The owner of Prairie Kitchen Catering started his cooking career in high school, slinging pizzas for pocket money. One restaurant job led to another and Neufeld soon discovered a passion for working with food.

Join us for a Free Press Fall Supper

The Winnipeg Free Press is hosting an elevated fall supper event based on the reporting for our months-long farm-to-table project. Join us as we bring our journalism to life from the page to your plate.

The Winnipeg Free Press is hosting an elevated fall supper event based on the reporting for our months-long farm-to-table project. Join us as we bring our journalism to life from the page to your plate.

Chef Matty Neufeld of Prairie Kitchen Catering has created a multi-course menu that will include the made-in-Manitoba ingredients included in this story.

Guests will enjoy his featured dish, dubbed the “Prairie Chicken Duo in a Field of Fall Flavours,” made up of sunflower-oil-poached chicken breast with confit chicken leg and chanterelle tortellini, Golden Prairie cheese fondue, butternut squash, beets, sage, toasted hemp seeds and sunflower shoots.

Local beer and spirit sampling is included in the ticket price and proceeds from the event will be donated to Harvest Manitoba.

All attendees must provide proof of full vaccination upon arrival, as per current public health restrictions.

Date: Sun., Oct. 17; 4:30 p.m.

Location: Whitetail Meadow, Lot 610-612 St. Mary’s Rd., 5 km west of Niverville (Google Map)

Individual tickets $150 each or $125 per person for groups of eight; visit wfp.to/fallsupper to purchase

Armed with Red Seal accreditation, he left Winnipeg to gain experience in kitchens across southeast Asia and Australia before enrolling at the University of Gastronomic Sciences in northern Italy.

The school was founded on the principles of the Slow Food movement — a global non-profit dedicated to promoting local food consumption and traditional culinary techniques — and the curriculum opened Neufeld’s eyes to the world of farm-to-table cooking. His days were spent toiling on small farms and turning the fruits of his labour into cheeses and flours that were later used in the kitchen.

“I was working with food from the ground up,” he says. “After travelling to different countries and visiting their agriculture systems, I came back to Manitoba and was really shocked with the bounty that we have.”

Neufeld started exploring his own backyard and incorporating what he found into the menu at Pineridge Hollow, where he was executive chef at the time. Those concepts live on in his catering company and he’s watched homegrown food gain wider purchase locally.

“The silver lining of (the pandemic) is that we really had to scale back where we’re grabbing ingredients from, so it’s opening people’s eyes to… what’s around us,” he says.

“Local food is super important to me, not only because the food tastes better, but you get to meet the people behind the products; the farmers, the artisans and producers.”

Suffice it to say, coming up with a made-in-Manitoba dish that would serve as the basis for the Winnipeg Free Press farm-to-table project was well within Neufeld’s wheelhouse.

“I really wanted to pick what the best ingredients of the (season) were and highlight those in a creative manner,” he says. “Which made me kind of push my limits.”

The result is a dish of sunflower-oil-poached chicken breast and confit chicken leg tortellini with cheese fondue, butternut squash, beets, toasted hemp seeds and sunflower shoots, made up of 10 ingredients grown, collected and created by Manitoba producers.

Over the last six months, reporters Randall King, Ben Sigurdson, Alan Small, Ben Waldman, Eva Wasney, Jill Wilson and Jen Zoratti, along with photographers Mikaela MacKenzie, Ruth Bonneville, Mike Deal and Alex Lupul, have ventured into farmer’s fields, forested parkland, cheesemaking facilities and chicken coops to document the life cycle of each ingredient.

These are their stories, from the field to the plate.

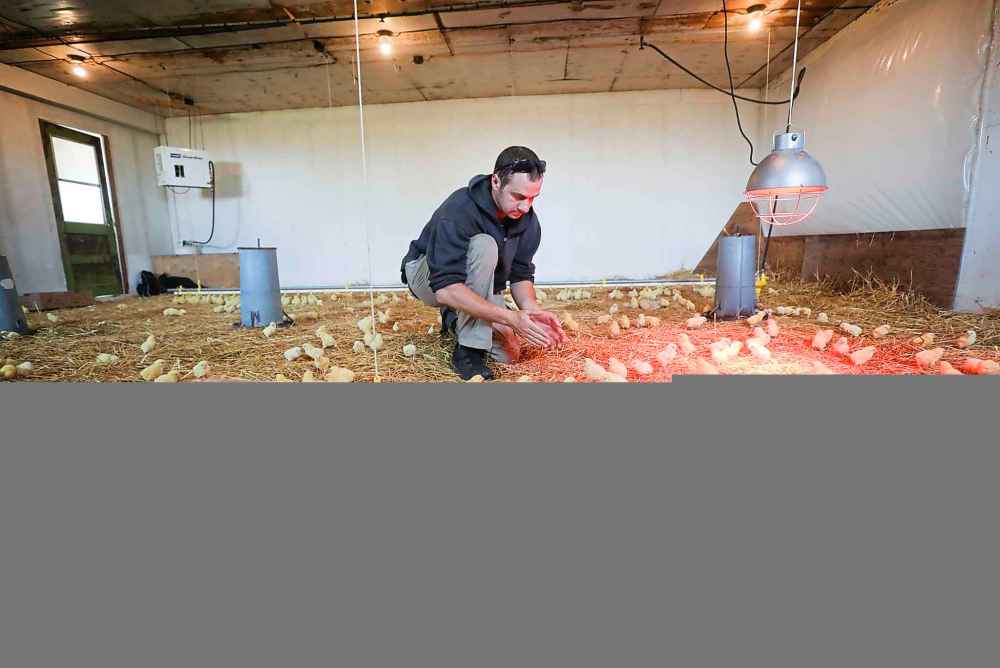

Andreas Zinn opens the door of his half-ton and out wafts a cacophony of cheeps. The 30-minute drive from Winnipeg to his farm near Springstein was loud and it was hot.

There are 800 day-old chicks purchased from a local hatchery in the cab of his truck; cardboard boxes with ventilation holes fill every available seat space. It’s a sunny day in late May, but Zinn has the heat cranked — the birds’ downy coats offer little warmth, so temperature regulation needs to happen externally.

“Typically, they would be sitting underneath the hen,” he says. “And underneath the hen is a certain humidity and 32 degrees.”

He carries the boxes of cockerels — young roosters — to a heated room in the barn. The floor is covered in a thick layer of straw and soon there are hundreds of fluffy, yellow chicks scurrying about. Treading carefully, Zinn scoops up handfuls of chicks and lines them under a hanging water feeder, testing the metal nipples as he goes to show the birds how to drink.

“There’s remnants of yolk in their stomach, so they can actually survive for three days without any water or food,” he says. “Of course, the faster they start eating and drinking, the better.”

Better is Zinn’s modus operandi. And he’s quick to point out all the ways his small-scale, free-range operation is better for the animals, better for the environment and better for the consumer than a traditional commercial farm.

“I think if people knew how animals were raised in commercial factory farms there would be a lot more vegetarians,” he says.

Zinn, 32, has seen both sides. The long white barn he’s standing in used to house 13,000 chickens in cages and large, crowded rooms. His grandparents purchased the 100-acre property in the 1970s when they emigrated from Germany and his mother, Monika, raised large flocks of breeder birds and young laying hens for more than 25 years. At the same time, she kept free-range backyard chickens to sell to neighbours and feed the family of eight.

“You walked into (the barn) and you knew it wasn’t natural,” Zinn says. “I could see the behaviour difference from chickens living outside versus a chicken in the barn.”

In 2006, the mother-son duo transitioned Zinn Farms away from the industrial model and started selling pasture-raised pork, chicken, eggs and rabbit directly to customers and restaurants.

The farm has a flock of about 300 laying hens. Like all the livestock, the birds have a free-range existence.

They spend summers out on the pasture pecking for bugs while simultaneously boosting the fertility of the soil with their droppings. In the winter, the chickens roam in the barn with nary a cage in sight.

The eggs at Zinn Farms are ungraded, meaning they haven’t been inspected at a federally registered facility. In Manitoba, ungraded eggs can be sold directly to customers — with proper labelling — but not to restaurants or at farmer’s markets.

Egg production drops off in the colder months and picks back up when the mercury rises. While the hens stick around on the farm for as long as they continue laying eggs, the meat birds are harvested when they reach a certain size.

The new chicks are meat birds. They’ll spend the next three weeks in the warm room, until their feathers come in and they’re big enough to range outdoors. At 12-weeks-old they’ll be sent to slaughter.

“We try to make it as pleasant of a life as possible,” Zinn says. “Then they only have one bad day.”

While Zinn Farms wasn’t immune to the plagues of the summer, they seem to have fared better than many Manitoba livestock producers. The heat was insufferable and the pastures were stunted by drought, but the chickens feasted on a glut of grasshoppers and feed milled on site.

The flock’s “bad day” comes in mid-August. The process starts at night, when the chickens are more docile and less likely to cause a stressful (for the birds) commotion.

Zinn and two farmhands close the barn doors, block out every bit of light and get to work loading birds into plastic crates. The room is dark and quiet, save for intermittent squawking whenever a chicken is handled.

The crates are stacked and loaded onto a flatbed trailer destined for Waldner Meats. The small slaughterhouse outside Niverville is one of three provincially licensed poultry processing plants in Manitoba. Owners Sandra and Angela Waldner have been working in the family business since they were kids.

“I was nine and grinding meat,” Sandra says. “This is what we’ve always done.”

The sisters took over from their parents, Harry and Sarah, two years ago and have seen steady growth in new customers and people raising chickens for their own consumption — especially during the pandemic.

While a large federal plant kills tens of thousands of chickens each day, the capacity at Waldner is less than 2,000. The government-inspected abattoir fills an important niche for small-scale farmers looking to sell their meat to restaurants and grocery stores.

“They’d have nowhere else to go,” Sandra says. “And if we let the big boys take over… forget about it, (the small farmers) are out of business.”

Killing starts at 7 a.m. sharp Monday through Friday during the summer chicken season. They also process pigs, cattle and wild game year-round.

Bleary-eyed employees start trickling into the building at quarter-to, donning hair nets and white or camo-printed smocks before taking their place on the kill floor. There are 12 people on the line, each with a specific job.

Today, Angela Waldner is removing vents, “which is assholes,” she says; a post-mortem incision necessary for organ removal.

The live birds are hung upside down by their feet before their throats are slit with an electrified knife, which stuns the animal and is mandated for humane killing.

The chickens are bled, spun through a mechanized plucking machine and moved down the production line — within minutes they look like the poultry found on a supermarket shelf.

Most of the process is done by hand and it’s monotonous work, the same task repeated 800 times over. The line stops and everyone files outside for a coffee break. Packaging and freezing starts in the afternoon and the order will be ready for pickup by morning.

Death is part of the business at Zinn Farms. It has to be. Andreas Zinn has gotten attached to animals before — the goats he raised as a teenager, the long-term breeding stock — but he’s matter-of-fact about the reality of animal agriculture.

“For any of the market animals, the reason why we have them is to be slaughtered,” he says. “To raise animals sustainably you have to have an end user for them.”

And while Zinn doesn’t shy away from the “bad day,” he’s more concerned with all the other days.

“It’s not a bad thing to eat meat because it was a living animal,” he says. “As long as the animal was raised the proper way.”

eva.wasney@freepress.mb.ca Twitter: @evawasney

SOMEWHERE IN MANITOBA – David and Caitlin Beer are driving down a dirt road, engulfed in a cloud of dust too dense to know exactly what type of car they’re driving.

Whatever it is, their vehicle barrels down the road, the gravel leaping off the ground and shooting into the air like bullets, before the 80-kilometer-per-hour dust ball settles, and out walk the couple, unsure of whether they’ll find today what they’re looking for: morels.

Where are they? You can’t know. It’s their secret, a little spot somewhere between Saskatchewan and Kenora, where, if the time is right, the foragers will be greeted by a bounty of morels, a sac fungus of the family Morchellaceae, genus Morchella, a grouping with more than 70 known species identified worldwide. Those 70 species can be divided into four clades: black, yellow, grey, and white.

You can’t know their exact co-ordinates — for fear of over-picking and improper management, they’re wary — but what you can know is that they are on Crown land, a right David has as a member of the Metis nation. Together, the Beers combine a heritage of farming and land management (from David), an advanced understanding of horticulture (from Caitlin’s college education), and a love of natural ingredients.

Once the dust settles, the Beers pull out two large orange buckets and set out for a grassy, well-treed area, on the hunt for yellows and blacks, the two types of morels most commonly found in Manitoba.

“These guys are really good at hiding,” Caitlin says as she pushes aside branches with the outside of her hand. “If mosquitoes are biting, it’s a good sign you’re in the right place.”

But the mosquitoes aren’t biting today: it’s a Saturday afternoon in June and it’s been a dry year. So dry, that the Beers are uncertain whether, even at this late stage in the normal morel season, they’ll put anything inside their buckets. Once in B.C., they found more than 200 pounds in a single day. With weather like Manitoba has had, they’ll be lucky to find a handful today.

(And true to form, the dry spring took a significant bite out of the harvest. When reached in early fall, the Beers, who run Wildland Foods, said they didn’t even get a quarter of the morels they harvest on average and would likely be sold out by Christmas.)

This is the work: go out on the land to find what grows, taking care to not harm the mycological networks beneath their feet, and dealing with the very real possibility of coming home empty handed.

With proper conditions, patience and expertise, morels can be found in good numbers. For eager first-time foragers, locating the conical, honeycomb ridges fungi can be an exercise in both frustration and futility.

“Is this a mushroom?” I asked David, with Caitlin off in the brush, her head scanning the ground like she was looking for a missing set of keys. “That,” David replied with no judgment, “is a dry cow turd.”

Not discouraged, I continued to stare at the ground, walking around like a hen pecking at seed. David and Caitlin each found actual morels, not cattle dung, and held up their prizes before tossing them into the bucket. Once cooked, the morels shrink down by a 10:1 ratio, so this is a start.

The field is clearly not a winner today. So, the dust ball rolls again to a second, also a dud, before reaching a third, with the impatient reporter looking for a shroom rather than a turd.

David and Caitlin amble into the area, and David points out poplar trees: yellow morels like growing under these, he says, so there’s hope. He finds one. Then another. “I guess this is the spot,” he says.

I break off from the group, and there I see it, a yellow cone sprouting underneath a fallen tree branch, hidden in plain sight as the sunlight illuminated its hollow body. I called David and Caitlin over to confirm this was the real deal.

“It is,” Caitlin said. “Feel it: Cool to the touch.” David takes out a small knife and cuts it at the stipe.

In the end, over five hours, seven usable morels are found. Next week, chanterelle season starts. The Beers will drive somewhere else to find where they’re hiding.

ben.waldman@freepress.mb.ca

WARREN — Clad in a white lab coat, his heavily tattooed forearm bearing the names of his daughters, Dustin Peltier is clearly no monk, but he has the patience of one.

Elbow-deep in a huge stainless-steel vat of milk, the 43-year-old chef is searching for large curds that might have escaped his reach. It’s part of a painstaking procedure that will eventually yield rich, pungent wheels of Golden Prairie, a washed-rind cheese based on a recipe handed down by Brother Albéric, a Trappist monk from the now-defunct Notre Dame des Prairies monastery.

Peltier, who also runs private catering company Loaf and Honey and got his start in busy local kitchens, says making cheese is “an act of patience with a different kind of reward. I won’t know if I did a good job for two months.”

While traditional Trappist cheese is aged in caves, Peltier works out of a retrofitted 1950s Manitoba Hydro job-site trailer parked on his parents’ land on Highway 6.

The cheese moulds and press were passed on to him by Brother Albéric when he retired in 2018, but some modifications to the recipe had to be made. After a protracted battle with the province over health and safety regulations, Peltier and his wife Rachel Isaak, also a chef, gave up their dream of making the cheese with raw (unpasteurized) milk the way the Trappist order has been making it for centuries.

Instead, they use non-homogenized whole milk from the Blumenfeld Creamery, a small dairy in southern Manitoba that uses a low-temperature pasteurization method where milk from local cows is heated to 63 C and then cooled back down.

And it all starts with the milk: 240 litres of it. There’s a 10 per cent yield, meaning 20 litres of milk results in two kilograms of cheese; each batch results in 12 wheels.

After the milk in the vat is slowly raised to 26 C, Peltier inoculates it with a bacterial culture, also donated by Brother Albéric, which converts milk sugars into lactic acid; if the culture is working, the liquid’s pH will drop. Next he adds rennet, a substance found in the fourth stomach of calves. It helps them process their mothers’ milk into solids and has a similar effect on the milk, curdling it.

As it gradually solidifies, Peltier tests the surface. “You want it to break with clean edges,” he explains.

He then cuts into it with a grid-like tool that resembles a giant potato masher (“I just call it my curd cutter,” he says when asked if it has a name), turning it into cubes that are like soft pillows of milk, tofu crossed with egg white.

He then moves on to using a large custom-made, stainless-steel stick with small twig-like appendages that emulates the tree branch monks would have used.

He doesn’t stir, but gently plunges the stick up and down to further break down the curds: “It’s not a witch’s brew,” he says with a laugh.

Eventually he reaches in to break up some stragglers by hand. It’s a delicate business; you want the liquid whey to seep out of the curd, but if too much is released, the cheese will be too firm.

When they’ve reached the right size — like a chunkier cottage cheese — Peltier scoops the curds out with a funnel-shaped sieve, leaving behind the whey, and places them into circular moulds, where they will sit for five hours to firm up. Then four-litre plastic milk jugs filled with water are attached to the moulds’ handles to exert 40 pounds of pressure on each one.

“Add (the weight) too fast and the curds haven’t firmed up, so they’ll just mush, or we’ll get a really, really hard cheese,” Peltier says.

After 14 hours, the fledgling cheeses are ready to be released from the moulds, doused in a thick layer of coarse salt and placed reverently in the aging “cave,” a cool concrete room set at 13 C and 90 per cent humidity. The aroma is funky and not a little footlike; Peltier explains that the bacteria that develops on the rind of washed cheeses is the same as what can develop on sweaty tootsies.

Even the wooden boards of the shelving have a part to play. Many of them were used in the monastery; the ghostly circular shapes of cheeses past are an indication of the rich bacterial culture that has infiltrated the wood and will contribute to the development of the rind. The planks also serve as a balancing agent, drawing out water if the cheese is too moist and helping to retain it if the wheel is too dry.

Now the wheels begin their 60-day aging process, but these diva cheeses will be given lavish attention throughout. The cheesemaker, with assistance from his mother, Silver Peltier, will hand-wash each one daily, anointing them with a brine containing a culture that helps the signature pale orange rind build up. (Lately he’s been experimenting, adding local ciders and beers and even scotch to the wash.)

After two months, the practically miraculous transformation of milk into Golden Prairie is complete. Brother Albéric would be proud.

jill.wilson@freepress.mb.ca Twitter: @dedaumier

An average day at Wild Earth Farms starts at 7 a.m. — earlier if it’s hot, much as it was in early summer.

Jeff Veenstra and his team convene for a morning meeting, go over the harvest list and get going in the fields as soon as possible.

Then there’s tractor work, hand weeding, cleaning and tidying before the farming ends mid-afternoon. From there Veenstra turns his attention to packing and delivering.

Located just north of Oakbank, Wild Earth is run by Veenstra and his wife Janna, with a peak crew of 10 helping throughout the summer. Jeff grew up on a carrot farm in Alberta before moving to Manitoba, while Janna was raised on a dairy farm near Wild Earth’s current location.

The 44-acre property features 10 acres of woods and the rest is fields, farmed sustainably and without pesticides or herbicides; they also rent 10 adjacent acres from Veenstra’s brother-in-law and another 10 from his father.

Now into their 10th growing season, Wild Earth sells produce and herbs to local restaurants and grocers, as well as at farmers markets. They also fill weekly and biweekly community supported agriculture (CSA) boxes sold directly to consumers. In total, the Veenstras and their team farm around 150 varieties of vegetables, herbs and fruits, including 10 different varieties of peppers.

The intense heat of the early growing season left Veenstra concerned about some crops, but not too stressed about others.

“Heat isn’t friendly to a lot of crops, but beets can withstand it,” he says. “Sustained heat’s not great; they’ll eventually put up a flower stalk, and the root is ruined… thankfully we had the roots established deep enough that they’re still sucking up moisture.”

On the herb front, Veenstra was pleased with how things were going early on. “Thyme, rosemary and sage are very Italian herbs,” he says. “If you think of Italy, on the hillsides, it’s warm and fairly dry. Those three can handle this heat, and they’re actually doing really well.”

The rain Veenstra had hoped would come shortly after the first Free Press visit failed to materialize in any significant way, but a wetter August was a welcome reprieve, albeit not ideally timed.

“For a lot of the crops the rain came about two or three weeks too late,” he said on a mid-September visit. “Our potatoes are much smaller than they should be. Some of our squashes are smaller than they need to be. The onions weren’t great except for the ones that were irrigated.”

Another early challenge was a series of visits from all manner of fauna. “The deer in particular were a nightmare up until it started to rain,” he says. Other visitors included a bear as well as coyotes, the latter of which only seemed to take interest in yellow watermelons. “And the bear just moved on,” Veenstra says with a laugh.

The Wild Earth team harvests different varieties of beets — reds, cylinders, goldens and chioggas — starting in mid-July through to the end of September.

“It’s a constant crop. We weren’t able to get our irrigation out to the far parts of our field where our beets were, but we got the rain right at the end and since they were still green and growing, it definitely helped them size up quite a bit more,” he says.

One of their most successful crops this year was butternut squash.

“Disease only thrives when there’s moisture sitting on the leaves, and since there was no early moisture, they stayed healthy the whole season,” Veenstra says in a final late September check-in. “They’re some of the biggest butternuts we’ve grown, and there are just so many of them. It was a great year for butternuts.”

After the hot start to the summer, the herbs — and the sage in particular — also enjoyed a great growing season. “The leaves are almost blemish free — big, beautiful plants — so it worked out really nicely,” Veenstra says.

Despite early concerns about extreme heat, Wild Earth’s diversity means the good and bad usually balance out.

“Even in a worst-case scenario, we’ll never have a terrible year because there’s always something that grows well,” he says.

“The fact that it’s dry and warm this fall means we should be able to get everything off the field, which is a huge accomplishment and means we’ll have a good harvest.”

ben.sigurdson@freepress.mb.ca Twitter: @bensigurdson

One of the newest trends in Canadian agriculture is older than the country itself.

Red Fife wheat was first grown in 1842 by Peterborough, Ont., farmer Dave Fife, according to the Canadian Encyclopedia, which recounts a legend that the kernels grown in Ukraine were scooped up from a ship in Glasgow, Scotland, and made their way to Canada and into the ground.

Folk tale or not, for the next 60 years the variety became the industry standard, grown, harvested and milled for flour by Canadian farmers to make bread, cake, pies and other foods families subsisted on during the 19th century.

Almost 180 years later, Red Fife wheat, supplanted at the turn of the 20th century by earlier-maturing varieties that get greater yields, grows again. Farmers across Canada are growing the historic seed using organic agricultural methods to cater to greater demand for chemical-free food and those seeking greater flavour from a loaf of bread offered at supermarkets.

Among those is the Unrau family, which owns Benco Farms and produces grain, lentils, vegetables and clover organically near MacGregor, about 125 kilometres west of Winnipeg.

Benco Foods makes flour from the Red Fife wheat, which they sell directly to consumers, including a stone-milled, whole-wheat variety that helps address a 21st-century problem.

“It has a lower gluten content so I have been getting a few customers who are gluten-sensitive that can use some of this wheat flour,” says Benjamin Unrau, who grew Red Fife wheat on about 40 acres in 2020. “It’s not gluten-free but they can use some.

“It definitely has a different flavour than (from) conventional wheat.”

At the turn of the 20th century, plant breeders crossed Red Fife with other varieties and eventually came up with Marquis wheat, which played a big role in turning the Prairies into the world’s breadbasket.

Red Fife’s genetic traits that make for high-quality breads remained in Marquis wheat and modern varieties grown today. While the old seed has faded away from widespread use it remained in heritage seed collections and caught the eyes of organic farmers in Canada.

There’s a tradeoff that farmers like Unrau makes when they decide to go the organic route. No herbicides or pesticides are sprayed on the grain to kill weeds and prevent fungal diseases, and the method has become a selling point for consumers who wish to reduce or eliminate chemical additives from their diets.

Organic grain farmers abstain from using chemical fertilizers too. Instead, time-worn methods, such as tilling manure into the soil and growing crops such as peas, lentils, alfalfa and clover that pull nitrogen out of the air, add life to the land.

No chemicals and fertilizers mean Unrau can save on expenses, but his Red Fife wheat and other crops are on their own to compete with weeds, which absorb the same nutrients and compete for the same sunlight and rain.

Sometimes fields are left fallow to revitalize them for the following year. The clover feeds cattle but doesn’t put cash in the bank though.

“It’s debatable how much input costs we actually save, especially if we skip a year for a cash crop. We often do that in our farms, plant clover and let it grow for a year,” Unrau says.

“Then you miss a crop, so you have an input cost there. Then you’re spreading manure and sometimes we have to pay (a price) per tonne for the manure we get and spreading it is not cheap.”

Unrau has only grown organic wheat, so he can’t compare it to how conventional farmers raise their crops. But there are certain rules that have remained for centuries.

“We seed it in and pretty much let God do the rest,” Unrau says. “(Red Fife) is obviously bred not so much for high yields, but it has better flavour and better nutrition. But I was very impressed with how mine was, just about 30 bushels to the acre. With the variety plus the organic (methods), that’s a pretty good crop.”

To mill the wheat into flour, Unrau trucks totes of wheat — about 40 bushels are in a tote — to a mill at a nearby Hutterite colony. Three different brands are created, with varying levels of bran, and enough is milled for his family’s use and to sell privately.

A portion of the seed is also preserved to sow in the future, and some is used to feed his chickens. (All-purpose Red Fife flour will be used to make tortellini for chef Matty Neufeld’s fall supper.)

While wheat flour is as popular as ever — bread-making became one of the COVID-19 pandemic’s favourite pastimes — the same crop can’t be grown on the same plot of land every year. For Unrau, that meant where Red Fife grew in 2020, it was time for something else that ended up enduring this summer’s drought.

Some of it was baled for winter feed for his father’s cattle and also to keep weed seeds off the land.

“I had oats and it didn’t do too terribly,” he says.

alan.small@freepress.mb.ca Twitter:@AlanDSmall

If growing organic hemp hearts in the Assiniboine Valley is a wholesome family business, the “hemp” part initially raised suspicion for River Valley Specialty Farms.

Apparently, for some, the sight of green fields lush with serrated hemp leaves, instantly recognizable from a billion T-shirts, evoked visions of illegal pot farms.

Kristen Gray, 43, and her brother James Kuhl, 41, own River Valley, which is located just off the Trans-Canada Highway near Bagot, 24 kilometres west of Portage la Prairie. She acknowledges a “stigma” was present when the company was formed in 2015.

“When we started, there were a lot of people that didn’t know about it and thought we were marijuana farmers,” Gray says.

“We did have people that would stop their vehicles, run through the ditch, grab some leaves and then run back into their cars and take off,” Kuhl says.

Be assured — it’s a business as straight as a hemp stalk. Gray and Kuhl presciently saw its potential when they purchased their parents’ farm six years ago.

Their parents had established the Northern Potato Co. in 1978 and it was primarily a conventional grains and potato operation, but also included asparagus.

“The asparagus was what really got us interested in and excited about specialty crops, growing healthy foods, super foods — that kind of thing,” Gray says. “So when my brother and I purchased the farm in 2015, we decided we want to focus more on specialty crops. So that included the asparagus and we chose hemp, a super food.”

Hemp, high in protein, iron, omega-3s and omega-6s, has a rich nutritional profile. “If you compare it side-by-side with flax and chia, it is superior,” Gray says.

At the same time, they switched the farm to an organic operation.

“Hemp is the perfect crop to transition to organic because it grows so tall, it out-competes the weeds,” Gray says.

Seeding started in April and the growing season got off to a promising start since a heavy mid-month snowstorm brought moisture to the region after a skimpy amount of precipitation over the winter. (The season’s largest dump of snow came as the federal government’s Canadian Drought Monitor for March 31 had warned of potential for “severe” to “extreme” drought in an area stretching from Regina to Winnipeg.)

“The snowfall helped,” Gray said in April when planting had begun. “But we could use some more moisture. The plant needs moisture to establish.”

By June, the young plants were smaller than usual, because the vast Prairie skies stayed miserly when it came to precipitation. Fortunately, hemp plants are built for such challenges.

“As it matures, it has a really, really long root. It can tunnel deep to find water,” says Gray. “So it is quite drought-resistant.”

That helped, as did the farm’s irrigation system, especially since the company faced other challenges. River Valley is divided into three businesses. They grow hemp. They process hemp seeds for export. But they also maintain the asparagus operation that was held over from their parents’ farm. Harvesting asparagus required 70 seasonal workers be brought in from Mexico, no easy procedure in COVID times.

“That crew was reduced due to the difficulties in bringing them across,” Gray says. “Getting the job done with fewer employees, plus the policies to put in place because of COVID was difficult. We bring them all here. We provide food. With quarantining 70 people, it can be stressful.”

The hemp harvest, which Gray expects to continue well into October, is comparatively less demanding of manpower. Only three people are required.

The harvest is done by combine, which gathers the seeds — containing the hemp hearts — from the heads at the top of the plant. Gray says they won’t know about the plants’ total yield until harvest is over. But they do know they will have a customer base that extends all over the globe.

“We don’t sell the hearts into the retail space, but we do sell bulk, so we have ingredient buyers, distributors, co-packers who buy the hearts in bulk,” says Gray. “And we’re selling throughout Canada and worldwide.”

randall.king@freepress.mb.ca Twitter: @FreepKing

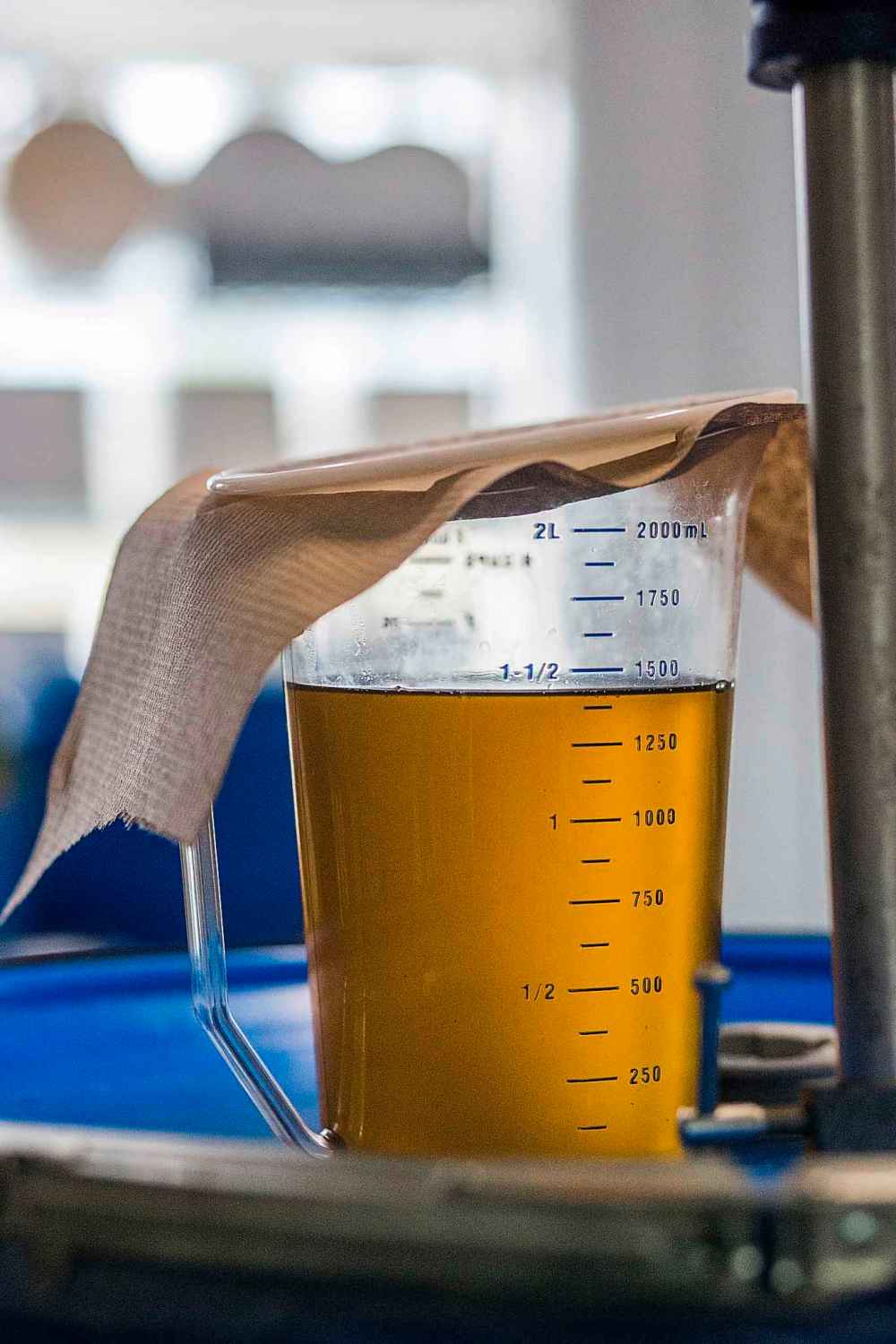

David Braun will tell you he produces sunflower oil. But to look at his gleaming, golden product, you’d think his job was to put sunshine in a bottle.

Braun is a member of Ploughshares Community Farm, a multi-family, mixed operation located southeast of Beausejour on the bank of the Brokenhead River. It’s an idyllic place with its own rhythm; true to its name, Ploughshares is both a farm and a community, with an eye toward living sustainably.

It’s a warm day in mid-August, and Braun has just received 21,000 pounds of Manitoba-grown sunflower seeds that he will soon process into certified organic cold-pressed sunflower oil.

If you’ve eaten anything from Tall Grass Prairie Bread Co. or its sister business, Grass Roots Prairie Kitchen, then it’s very likely you’ve tasted Ploughshares’ earthy sunflower oil in their baking, dips and spreads. In fact, a sunflower oil press was set up at The Forks Market until Braun brought the operation to the farm in 2018.

So, why sunflower oil? “It’s really four or fivefold,” Braun says with a laugh. “First is the taste. The taste, the smell, the feel — it feels really nice. It’s got a good a really smooth feeling; it’s incredibly good for your hands, for your skin, for your hair. And I really believe in the health virtues of it. It’s high in vitamin E and omega fatty acids. It’s great in cooking and baking.”

Sunflower oil smells delicious; Braun’s entire operation smells like a bakery. The oil press is tucked away behind a false wall in the commercial kitchen at the farm’s straw bale house, which makes for an impressive reveal.

The seeds are delivered by truck to the outdoor bin, and are fed into the hopper via hose through the window. From the hopper, the seeds are funnelled down into the press, where they are squeezed by a giant screw.

The oil from the seeds flows into a huge blue barrel, while the seed cake, composed of crushed seeds, is extruded into another barrel. The pieces of waxy seed cake, which look like broken black crayons, are used as animal feed.

“We actually sell this to a dairy farmer who claims it’s remarkable for getting his cows to come in heat,” Braun says with a chuckle.

Braun will press for about 12 days at a time, producing about 700 litres a session, or four of those blue barrels. Once the oil is collected, it will be given a couple weeks to settle. This is a key part of the process; sunflower oil straight from the press doesn’t look all that appetizing, he says.

But once those fine seed-cake particles drift to the bottom of the barrel, what’s left behind is translucent liquid gold. “It gets so gorgeous,” Braun agrees. “There’s no doubt about that.”

Braun then uses a stainless steel food-grade pump to transfer the settled oil into pails, which is how they are sold to Tall Grass and other customers. Braun also bottles the oil and sells it that way, too, with a pretty, rustic sunflower label designed by his son.

Transferring oil to pails and bottles can, occasionally, be a messy job. That’s why Braun always has a box of old copies of the Free Press available. Nothing cleans up sunflower oil like newsprint, apparently.

• • •

Before you can have oil, you need seeds. And before you can have seeds, you need flowers.

Nestled in the rolling hills near Treherne, you’ll find Dan and Fran DeRuyck’s organic sunflower field. Owing to this summer’s drought, this year’s crop is noticeably short. It’s not the kind of field that would attract selfie seekers jockeying for position among tall, Instagram-worthy yellow blooms.

Get closer, though, and you’ll see resilient flowers that are still turning their faces toward the sun and finding a way, anyway. The field is not irrigated, so it relies on rain. “We’re at the mercy of Mother Nature,” says Dan, surveying the mix of mature flowers, heads heavy with seeds, and the cheerful late bloomers that are still attracting fat, thumb-sized bumblebees. Organic farming means no chemical interventions can be used.

The DeRuycks’ Top of the Hill Farm specializes in certified organic grains, flours and flakes. And, as of about 15 years ago, organic sunflower seeds.

The DeRuycks used to provide the seeds for the sunflower oil press at The Forks Market, and have continued working with Braun over at Ploughshares. “David’s our main buyer for sunflowers,” Dan says. “We grow about 40 acres every year for him.”

Sunflowers, he says, have been a welcome addition to their crop rotation because they can be harvested later — usually late October into early November.

“We generally need a killing frost to kill the plant, and then they’ll do what’s called a dry down,” Dan explains. The sunflowers, stems and all, will turn brown. “Once the moisture gets to a certain level it’ll store, we’ll start harvesting it.”

The seeds will then be cleaned at the DeRuycks’ cleaning and sorting plant, and will be ready for Braun to press by February. Once harvested, that’s it for sunflowers on this particular field; they’ll be rotated to a different field next June.

“We like to do sunflowers every four years on the same property, just disease wise and production wise,” Dan explains.

And hopefully, next year will be better.

“That’s what farmers always say,” Dan says with a laugh. “‘Next year will be better.'”

jen.zoratti@freepress.mb.ca

Savour our fall supper

Elevated multi-course local dinner, with proceeds donated to Harvest Manitoba

This farm-to-table project has come full circle in a way we couldn’t have imagined at the outset, when a third wave of coronavirus cases were surging in Manitoba and the province was in a state of lockdown.

This month, we are hosting our first-ever Free Press Fall Supper — an elevated multi-course dinner celebrating the bounty of the season and the local chicken, mushrooms, flour, eggs, sunflowers, hemp seeds, cheese, herbs and vegetables featured in this project.

Road-trip recipe

The farm-to-table reporting and photography team travelled hundreds of kilometres across the province this summer to produce this feature.

Below is a piece-by-piece breakdown of the dish and where in Manitoba each ingredient is grown, processed or found.

Protein: Chicken from Zinn Farms, Springstein

Pasta: Red Fife flour from Benco Farms, MacGregor; eggs from Zinn Farms

Mushrooms: Wildland Foods, Shortdale

Vegetables and herbs: Wild Earth Farms, Oakbank

Cheese: Loaf and Honey, Warren

Sunflower oil: Ploughshares Community Farm, Beausejour; Deruyck’s Top of the Hill Farm, Treherne

Hemp seeds: River Valley Specialty Farms, Bagot

If you enjoyed reading the stories behind these ingredients, we hope you’ll join us on Sunday, Oct. 17, for a real-life feast.

Chef Matty Neufeld’s featured dish, “Prairie Chicken Duo in a Field of Fall Flavours,” will be the star of the menu, surrounded by seasonal starters and dessert inspired by Manitoba flavours. Beer and spirit sampling will be provided by Fort Garry Brewing Co. and Capital K Distillery.

The meal will take place at Whitetail Meadow, a family-owned wedding and event venue just outside Niverville and 20 minutes south of Winnipeg.

The venue’s main hall is in a retrofitted barn that was built in the 1940s and slated for demolition before it was moved to its current location and meticulously renovated. The grounds include an onsite cottage, vintage windmill and picturesque pond.

Proceeds from the Free Press Fall Supper will be donated to Harvest Manitoba, which distributes much-needed meals to more than 80,000 children, families and adults every month through its network of food banks across the province.

Visit wfp.to/fallsupper for more information and to purchase tickets for this special event.

History

Updated on Friday, October 1, 2021 2:08 PM CDT: fixes style issues