Conflict in context Exhibition wades into thorny issues of Mennonites at war abroad, ensuing personal battles at home

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 30/07/2021 (1593 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

When it comes to talking about war and peace, Mennonites might just have a bit of conflict.

Exhibition preview

Mennonites at War

Mennonite Heritage Village, 231 PTH Hwy 12, Steinbach

• Online exhibit at mennoniteheritagevillage.com

• Runs until Nov. 14

• Open 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday to Saturday, 11:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. Sunday

• Admission: $12 adults, $10 seniors/students, $6 children 6-12, ages 5 and under free

Some hold tightly to their historical pacifism, others argue it is their duty to serve their country and many just live in a grey zone.

The new exhibit titled Mennonites at War, on display until Nov. 14 at Mennonite Heritage Village in Steinbach, wades into that discussion fully armed with photographs, personal artifacts and historical context.

“It’s Mennonites going to war and it’s the idea of Mennonites at war with each other over the topic of peace,” says senior curator Andrea Klassen of the temporary exhibit.

“What is relevant to us today is how we relate to people we disagree with. And how do we maintain relationships between individuals and families when we don’t agree with each other?”

Occupying 1,200 square feet in the museum’s gallery building, the exhibit is thought to be the first at a Canadian museum to specifically address the involvement of Mennonite men and women as soldiers, medics and nurses in recent wars, Klassen says.

“I think it is a controversial topic,” she says of the exhibition, which features a military rifle, uniforms and mannequins dressed as war-time medics carrying a wounded soldier on a stretcher.

“I think the amount of artifacts we have relating to soldiers might jar people.”

About three-quarters of the items on display were already part of the museum’s collection, with the gaps filled by loans from the Fort Garry Horse Museum and Archives, Steinbach Royal Canadian Legion 190 and personal items from families.

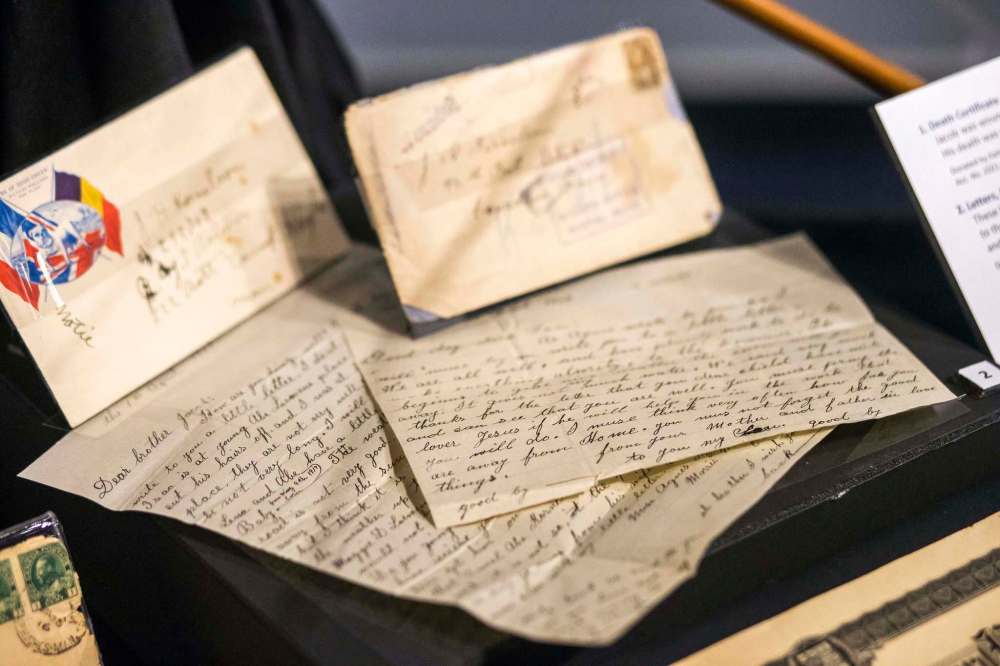

One collection of letters and documents from the family of Jacob Harms Cornelson (also spelled Kornelsen) of Rosenort, who enlisted in the Canadian army in 1916, was offered to the museum weeks after the exhibit was completed, said Klassen. Since the museum was closed until mid-July under public health orders, there was time to add the young soldier’s death certificate and letters Cornelsen’s sisters wrote to him, returned to the family after his death at Vimy Ridge on May 4, 1917.

“So few Mennonites served in the First (World) War because they were exempt and that exemption was upheld by the government,” says Klassen, referring to the rarity of Mennonite war artifacts from that era.

Thousands of Low German-speaking Mennonite emigrated from Russia to Canada in the 1870s to avoid compulsory military service, with the Canadian government promising them exemption from participation in the military.

Mennonite leaders negotiated alternative service arrangements during the Second World War, enabling about 7,000 Mennonite men to serve time as conscientious objectors, constructing roads, fighting fires, logging trees or building national parks.

Based on the teaching of Jesus Christ to love their enemies, Mennonites have a long history of promoting non-violence and avoiding participation in the military, although it is clear from archival records many Canadian Mennonites still enlisted, especially during the Second World War.

An estimated 4,500 Mennonites served in various branches of the Canadian military, including 55 women.

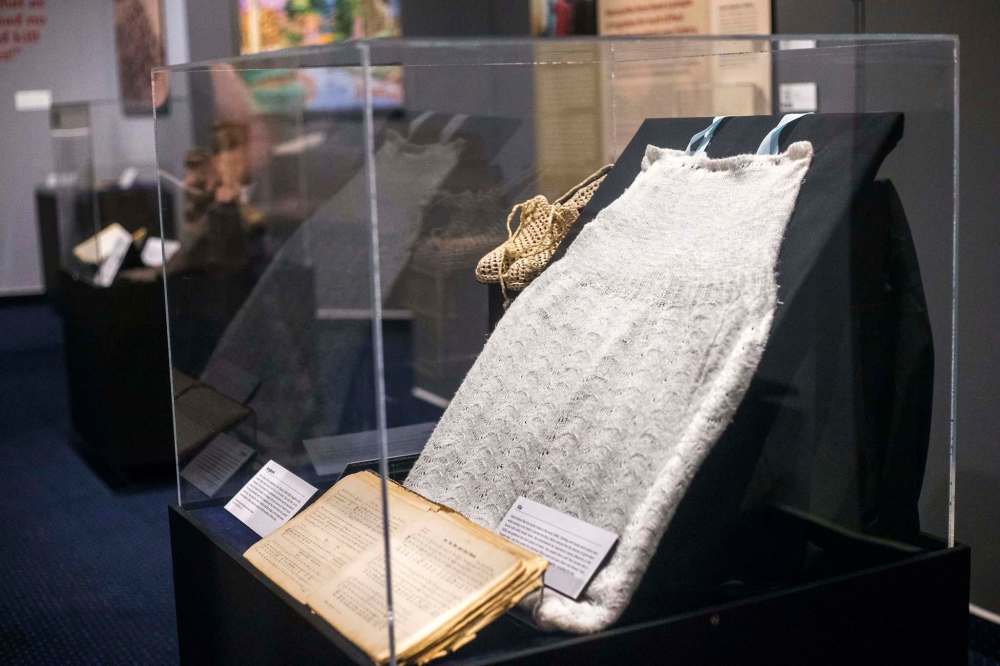

That number does not include women such as Susan Janzen Ciske, who served in the United States army nurse corps after working in hospitals in Altona and Detroit. In addition to her identification tags, passport and photo, a wooden music box with the name “Jan” inlaid on top is on display, built by a Czech prisoner of war Janzen befriended. Jan was Ciske’s nickname, based on the first syllable of her family name.

“The story the family tells is he was trusted and he was allowed outside the camp to scrounge for scraps of wood to make this,” said Klassen of the still functional musical jewelry box.

The exhibit also highlights the wartime courtship of German soldier Jacob Rempel and Kaethe Gäde, separated in Germany in 1941 and reunited in Winnipeg on Dec. 25, 1948. During his years as a medic and then a prisoner of war in France, Rempel wrote to Gäde twice a week, with both parties saving the letters, which now form a family archive held by their son Peter.

Initially part of the Soviet army, Jacob Rempel felt he had no choice but to join the military or be shot, says his son. He later joined the German medical corps after he was captured by the Germans.

“He was always very grateful he never had to fire a bullet at an enemy soldier and never took a life,” says Peter Rempel.

Once settled in Winnipeg, the newlyweds joined Sargent Avenue Mennonite Church, which was populated by recent refugees and immigrants who had similar stories of involvement in the war.

“He had many peers who had all served in the military on the German or Soviet side so there was a lot of understanding and not condemnation among his peers,” the Wolseley resident says of his late father.

That wasn’t always the case for returning Mennonite soldiers, especially Canadians who chose to enlist rather than claiming conscientious objector status, says historian Hans Werner, featured in videos accessed through QR codes in the exhibit.

“It was thought they (Europeans) had no choice and the Canadian soldier had a choice,” says the retired University of Winnipeg history professor.

Some Canadian Mennonite men had their objector status denied, while others only objected when they were forced to enlist and then realized their faith convictions did not allow them to don the uniform and participate in basic training, says Klassen. Others enlisted to serve as medics, with the understanding they did not have to carry weapons.

Several Mennonites deserted rather than comply with the military and faced court martial as a result, including five men whose photographs and stories are featured in the exhibit.

Whether they objected, joined the military or were charged with desertion, most Mennonites cited their Christian beliefs as the reason for their decision, Klassen says.

“When we talk to Mennonites about pacifism or objection to war, they often talk about faith,” she says.

“It’s taking this issue of faith and people come to different conclusions.”

That difference needs to be acknowledged and understood as part of the Mennonite story in Canada and abroad, says Werner, who wrote a book about his father’s life, including his time as a Red Army soldier, a German captive and then a draftee into Hitler’s war efforts.

His father shared his wartime experiences with his family and friends, but many others kept silent.

“It’s part of coming to terms with a Mennonite past and it tells us the martyr story isn’t the only one,” he says, referring to how conscientious objectors were often portrayed.

“We haven’t lived through simple times and sometimes been compromised and made compromised decisions.”

That thinking may be instructive today, when Canadians don’t agree on other issues, such as the need for or efficacy of vaccines against COVID-19, Klassen says.

“History has a way of telling us how we handled or mishandled things in the past,” she say.

“These are deeply felt issues. Whatever side you’re on, these are deeply felt issues on both sides.”

brenda.suderman@freepress.mb.ca

The Free Press is committed to covering faith in Manitoba. If you appreciate that coverage, help us do more! Your contribution of $10, $25 or more will allow us to deepen our reporting about faith in the province. Thanks! BECOME A FAITH JOURNALISM SUPPORTER

Brenda Suderman has been a columnist in the Saturday paper since 2000, first writing about family entertainment, and about faith and religion since 2006.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

The Free Press acknowledges the financial support it receives from members of the city’s faith community, which makes our coverage of religion possible.