Miigwetch for the music Winnipegger Dave McLeod's Instagram project aims to open listeners' ears to a vast world of Indigenous artists

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 30/06/2021 (1626 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

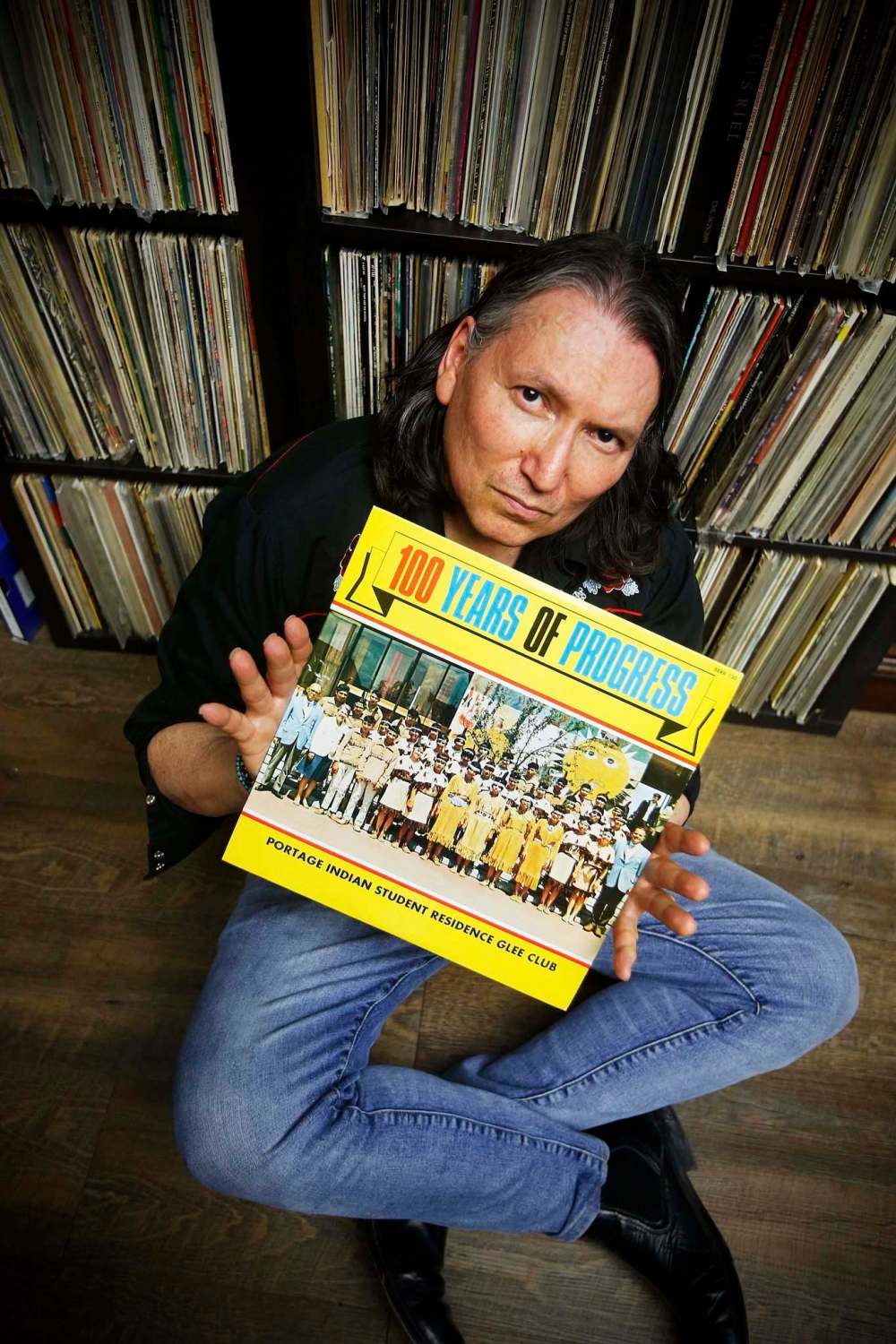

‘Hoka hey!” is a Lakota expression that translates roughly as “let’s roll” or “let’s do this.” It is also the phrase Dave McLeod, CEO of public radio network Native Communications Inc. (NCI-FM), went with for his newly minted Instagram account, HOKA Indigenous Music, which focuses on Indigenous artists, past, present and future, from regions throughout Turtle Island/North America.

“‘Hoka hey’ is widely announced by MCs at powwows in an energetic manner and that’s the spirit I’m trying to capture with my (Instagram) project,” McLeod says, seated on a screened-in porch attached to the front of his Elmwood-area home, a block east of the Red River. “Lots of times, I would go online and see record collectors holding up Beatles or Stones albums and getting thousands of likes, so I began to think, why not do something similar with my stuff?”

Ah, his “stuff.”

McLeod, who is Métis and Anishinaabe from Pine Creek First Nation, possesses arguably the largest collection of Indigenous music in the land, close to 10,000 vinyl albums, 45-rpm singles, CDs and cassette tapes. Since March, McLeod, also the curator of the Calgary-based National Music Centre’s Speak Up! exhibition, which, to quote the NMC website, “recognizes powerful Indigenous voice in music,” has been posting photos and audio clips drawn from his lot on a near-weekly basis.

Not only does he highlight world-renowned singer-songwriters such as Buffy Sainte-Marie and Robbie Robertson, he also draws attention to less-heralded talents such as the Klaudt Indian Family, a gospel group from the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota that formed in the 1930s, and Billy Lee Riley, a rockabilly singer of Cherokee descent who was signed by the legendary Sun Records label around the same time as Elvis Presley and Carl Perkins. (In case you’re wondering, yes, the 1973 chart-topper Half-Breed by Cher, reportedly 1/16 Native American on her mother’s side, counts; no, American pop group the Raiders’ No. 1 smash Indian Reservation (The Lament of the Cherokee Reservation Indian) doesn’t.)

“I love collecting albums and love finding treasures I never knew existed,” McLeod continues, reaching over to turn down a stereo tuned to NCI-FM’s Indigenous Music Countdown, a weekly Top 40 program he’s heavily involved with. “Because I’m part of the community, I felt it was my duty or responsibility, or whatever you want to call it, to share all this fantastic music with the world, even if it’s only one or two songs at a time.”

• • •

McLeod, in his mid-50s, remembers the moment like it was yesterday.

In 1980 he was living in Thompson with his parents and two siblings. Fifteen years old and already a self-described “music nut,” he was babysitting for a family friend when he spied a stack of vinyl albums in a corner of the living room. The kids he was looking after were in bed, perhaps there was something he could throw on to help pass the time.

Flipping through the albums — almost all were by radio-friendly acts such as Boston, the Steve Miller Band and the Eagles — he paused at one titled Original Recordings by Ernest Monias. He was primarily into punk rock at the time — the Ramones, the Cramps, Dead Kennedys, that sort of thing — so he was surprised to see “a brown man like me” on the cover of a record album, referring to Monias, born and raised in Cross Lake Cree Nation and dubbed “Elvis of the North” by his fans.

“The second I heard Ernest’s voice coming out of the speakers I instantly fell in love with his music,” McLeod says, holding up a copy of the album in question. “It kind of lifted the curtain up in a way, letting me know that native music existed and that it was every bit as good, if not better, than what I was listening to already.”

McLeod’s collection grew slowly; four or five times a year he’d accompany his parents to Winnipeg, at which point he’d spend a few hours poring through Portage Avenue vinyl meccas such as Records on Wheels, Sound Explosion and Mother’s Music. That is, when he wasn’t combing the bins of the Country Music Record Centre on Selkirk Avenue, run by a fellow he came to know as Charlie.

Owner Charlie Ward may not have been Indigenous himself, but the walls of his iconic store were lined with 8×10 photos of Indigenous artists who recorded for Winnipeg-based Sunshine Records. Through Ward, McLeod discovered the likes of Reg Bouvette, Len Fairchuk and Gloria Desjarlais, whose recordings he would study the second he returned to Thompson.

McLeod’s vinyl pursuit was placed on the back burner in the late 1980s and early ‘90s, when he moved first to Calgary to study broadcasting at the Southern Alberta Institute of Technologies, then to Toronto, where he took television production at Ryerson University. He was still in Toronto when he met Brian Wright-McLeod (no relation), who taught Indigenous Studies at York University. That would have been 1995, he figures, right around when Wright-McLeod was commencing to write The Encyclopedia of Native Music, an exhaustive guide with close to 1,800 entries that was published in 2005.

“He allowed me to go through his vinyl and cassettes and that was very inspiring for me,” he says. “I used to dub songs on a mini-disc recorder, just to have a copy for myself before I could find the real thing. He had all these alternate recordings I’d never heard of, like Blackfire, a Native American punk rock group, and Laura Visin, who incorporated a disco look with an Indigenous vibe in the way she dressed. I was like, ‘Man, who knew?’”

• • •

McLeod, winner of a Canadian Aboriginal Music Award for his work promoting Indigenous music through radio, looks like a kid in a candy store when invited to do a little show-and-tell.

Leafing through wooden crates into which records are filed according to genre — folk, country, rock, pow wow, even spoken word — he first pulls out a 78 rpm recording by jazz singer Mildred Bailey, a member of the Coeur d’Alene Tribe who recorded with Benny Goodman and Bing Crosby in the 1930s and ‘40s.

“She learned to sing by participating in tribal ceremonies and from what I’ve read, was the first female big band singer in America, “ he says of Bailey, who came to be known as the “Queen of Swing,” and was inducted into the Big Band and Jazz Hall of Fame in 1989, 38 years after her death at age 44.

Prefacing another fave with, “These guys are fricking amazing,” he hands over an LP titled simply, The Fenders, recorded in 1961. “In the early 1960s, a number of Navajo-Diné country and western bands became very popular in and around Navajo territory — northeastern Arizona, southeastern Utah — and the Fenders were probably the best of the bunch.”

Then there’s Redbone, which became the first Native American band to score a Top 5 hit on Billboard with their 1974 single Come and Get Your Love, featured prominently on the Guardians of the Galaxy soundtrack. “For bands like Redbone to break into the mainstream, it was almost as if they had to be so good that they couldn’t be ignored,” he says, reading through the liner notes from the group’s 1973 release Wovoka, which contains the single We Were All Wounded at Wounded Knee, deemed too controversial for North American radio audiences, but a No. 1 hit in Belgium and the Netherlands, nonetheless.

“Also, this,” he says, holding up a copy of Instincts by American new wave band Romeo Void, which contains the post-punk classic A Girl in Trouble (Is a Temporary Thing). “I was a big fan of Romeo Void when they first came out in the ‘80s, but it wasn’t until I met Brian (Wright-McLeod) that I learned Debora Iyall, the lead singer, was Indigenous.”

Besides serving as a music library, McLeod’s cache also holds a tremendous amount of historical value. Through the years he’s unearthed a handful of albums recorded by residential school choirs; he shakes his head staring at the cover of one called 100 Years of Progress, credited to the Portage Indian Student Residential School Glee Club. He also owns the lone album recorded by filmmaker and activist Alanis Obomsawin, born in 1932 in New Hampshire on Abenaki Territory.

“Alanis moved to Canada when she was a kid and was singing about murdered and missing Indigenous women in the early ‘80s already,” he says, passing over a copy of her 1984 album, Bush Lady. “It’s a stark reminder of just how long some of the issues we face today have been going on.”

McLeod also keeps a separate box filled with albums featuring cover art that is Indigenous in nature, despite the fact the applicable artists aren’t native in any way. Think David Lee Roth’s solo effort Eat ‘Em and Smile, which depicts the former Van Halen frontman in full warpaint; or K-Tel Records’ Kooky Kountry, with a front illustration of bare-chested musicians wearing headdresses, a “nod,” he guesses, to Side 2’s Running Bear, a tone-deaf, albeit No. 1, hit for Johnny Preston in 1960.

“I used to make an effort to search these kinds of things out, more to say, ‘Will you get a load of how stupid this is?’ than anything else. But at a certain point I realized there were so many that I was like, what’s the point, why even go to the trouble of looking?”

While the majority of people who collect records do so as a hobby, McLeod has been able to marry his pastime with his professional career, by adding records he picks up at flea markets and second-hand shops to NCI’s vast playlist. Even better, he’s been afforded the opportunity to interview many of the artists whose music he enjoys, a list that includes Grammy Award winner Rita Coolidge (Cherokee), Canadian duo Kashtin (Innu) and Stevie Salas (Apache), the latter a rock guitarist who has played with everyone from Mick Jagger to George Clinton, and has served as musical director for TV reality show American Idol.

“That, to me, has been the end-all,” McLeod says. “I mean, to sit in a room with Shingoose (Ojibwe singer-songwriter who died in Winnipeg in January) and listen to him talking about the time he was recording in New York and in walks John Lennon. Here’s this First Nations man from Manitoba and one of his fans is a Beatle? How good a story is that?”

The former punk rocker, his shoulder-length hair now speckled with grey, laughs when asked if he ever kicks back now and again and plays songs from his youth, tunes such as I Wanna Be Sedated by the Ramones or My War by Black Flag.

“I do still enjoy other genres (of music) but unfortunately I don’t have enough time to get to it. I’m not exaggerating when I say my time is 95 per cent focused on Indigenous music.

“Not that I’m complaining. It’s as good as it gets.”

To see what McLeod is posting about next, go to his account on instagram.com.

david.sanderson@freepress.mb.ca

Dave Sanderson was born in Regina but please, don’t hold that against him.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.