Scraps, shards and stories River gives up its gifts to mudlarks, who comb the banks for pieces of history

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 07/06/2021 (1650 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Mudlark, meaning a person who scavenges in river mud for items of value, is a Victorian-era term that emerged out of the muck of the River Thames and into the language.

My mudlarking career has its roots in the place where the word originated. In 2009, I visited the United Kingdom, and my daughter, then 8, and I visited the Thames foreshore, picking bits of pottery and porcelain off the pebbly bank.

Nowadays, the term refers to hobbyists interested in gleaning bits of history and beauty from the banks of any waterway.

In the fall of 2020, I became a pandemic mudlark on the shores of the Assiniboine. Unable to travel and in self-isolation, mudlarking became a treasured solo activity. The river waters were low and much of the bank was exposed; the ground was flat and dry, and the walking easy. I recalled fondly my day on the Thames with my daughter, and set my gaze to the ground to glean once more for treasure.

● ● ●

In mid-May, I got a message from Ariel Gordon, a writer and fellow mudlark.

Hey, Sally, you want to go mudlarking on the Red? There’s lots of stuff on the west shore of the river across from the Winnipeg Rowing Club.

She knew about this place from past casual larks, but more of the bank was exposed than she remembered. I was overwhelmed by how much was there. Old broken glass bottles from the breweries that lined that part of the shore were strewn about, many with the embossed wording:

THIS BOTTLE IS OUR PROPERTY AND ANY CHARGE MADE THEREFOR SIMPLY COVERS ITS USE WHILE CONTAINING GOODS BOTTLED BY US AND MUST BE RETURNED WHEN EMPTY.

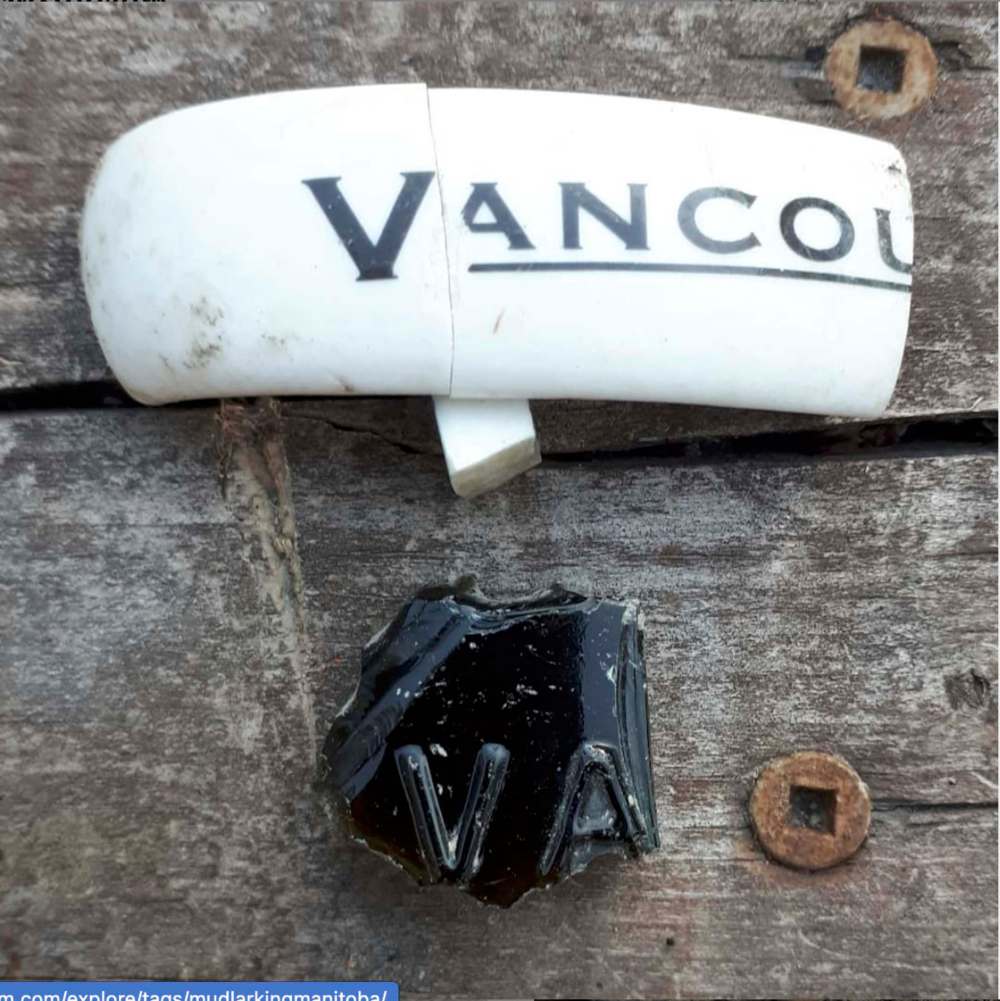

These bottles, marked with WINNIPEG, displayed the brewery’s name, usually Blackwoods or Drewry. These historical breweries had their operations along the rivers. The strip of land Ariel and I were exploring was just behind the original Blackwoods brewery built in 1904 on Mulvey Avenue East.

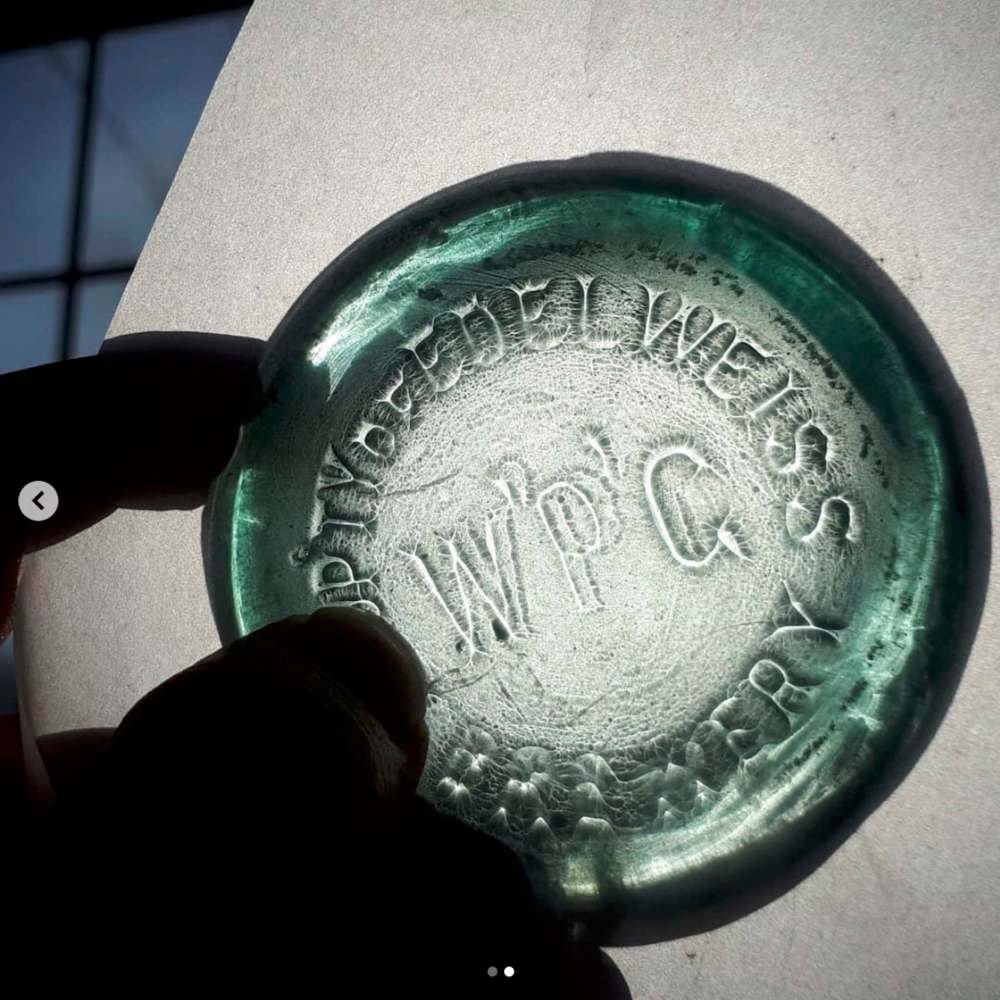

Any glass with embossed wording can easily be researched. Take, for example, the bottle end I found with PROPERTY of EDELWEISS BREWERY — W’P’G on it. I discovered a brief but interesting reference to this brewery on the Manitoba Historical Society website. Formerly the Benson Brewery, it was bought out by Arnold Riedle at the turn of the century and renamed the Edelweiss Brewery. It operated under that name until it was “ransacked by returning World War I vets in 1919.”

Ariel discovered another unique embossed item — milk glass jar bottoms with the words: MACLAREN’S IMPERIAL CHEESE. Two steer heads with horns appeared as small raised bumps in the middle of the trademark embossing. I found one, too; posting the find on Instagram, I was surprised to discover not only the jar’s historical association with Conservative politician and businessman Alexander Maclaren (1854-1917) of Perth County, Ont., but also that this innovative spreadable cheese product is still sold today by Kraft. Early advertisements for the cheese bore these words of Maclaren’s philosophy: “The road to prosperity lies through the desires of your customers.”

While the history of the bottles was fascinating, I also found their thick, bubble-filled glass appealing; the colors, too — aqua or purple — were beautiful. I took a few of the broken bottles into Prairie Studio Glass, where I asked artisan Matthew McMillan if he could cut them down into tumbler size. He remarked on their beauty, and also on how the crudity of their manufacture spoke of another era of material production where a bottle — expensive to make — was to be returned and reused in perpetuity.

Alongside all the broken glass were also shards of ceramics — porcelain, stoneware, earthenware — much more than I’d seen anywhere else. A couple of mudlarkers in Wales I follow on YouTube play a game called Plain or Patterned? where they flip a shard of ceramic to see what lies on the other side. If there’s a pattern, one delights in seeing the colours or recognizing the scene depicted. The fun of mudlarking these bits is imagining what the rest of the pattern or scene looks like. Where did this vine or tendril go on the border of that plate? How many roses were on that bush on that cup? Where are those birds flying to?

As a history and word hunter, I also collect ceramic shards that have the pottery marks on them. In this way, I have travelled to the great ceramics manufacturing centres of the world, such as Staffordshire, England, and Limoges, France; and to Czechoslovakia and Japan. I have dined off “hotelware” pieces made for railways and park hotels. My flour and sugar has been stored in Redwing stoneware crockery from Minnesota with its wonderfully stylized number markings and redwing logo.

Pottery marks are easily researched, and even a few words on a shard can lead to discoveries of interesting places, histories of industrial production, and notable personalities of invention and design.

Some of my best finds since I started my pandemic mudlarking were found on that stretch of riverbank, including not one, but two horseshoes. As Ariel and I headed back to our cars laden with treasure, a young woman with a bob cut and a backpack slung over her shoulder saw me with my two horseshoes in hand. In a friendly voice, she introduced herself — “Hi, I’m Tee-Jay! What you got there?” When I showed her my horseshoes, she asked if she could have one. I happily gave it to her. Maybe it would give her the luck bestowed on me when I found my first horseshoe on the Assiniboine a week earlier: a COVID-19 vaccine appointment the very next day.

● ● ●

The stretch of bank Ariel and I explored over the week, in separate trips and with each other, was unusual. The river was at a historical low. At the same time, the number of COVID-19 cases was rising along with hospitalizations. More lockdown restrictions were announced. There were to be no more indoor or outdoor gatherings in private residences. This meant that my family, who had been meeting on weekends, could no longer visit at home with each other. I suggested we lark together, and on Friday, we went out to the bank Ariel and I had explored.

Within minutes, my husband found a whole vintage Heinz bottle; my daughter, meanwhile, picked up an almost complete Drewry bottle with all the embossed messaging on it intact. Only the neck was broken. My son was busy taking photos — his pandemic project is to take more analogue photos and make prints at the photo shop where he works. There was plenty to photograph here: the glittery glass-strewn shore, the rippling waters of the river, the geese and ducks, and even a bald eagle flying overhead, the sun setting behind the spires of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights.

I thought wistfully of my earlier mudlarking ventures on the Assiniboine, where there wasn’t as much to be found. Had the Red River now spoiled me with its treasure? How could I go back to picking up golf balls and plastic toys?

But then the waters shifted. The lock at St. Andrews was turned on to bring the Red River to more navigable levels for watercraft. The following week when Ariel and I returned to our spot, it was completely submerged. “Remember that tire I sat on while picking through my finds?” she said, scanning the river. “It’s out there now.” I asked if she thought the water level might go down. She shook her head. Not this summer, she said. And maybe not ever.

So, were we just lucky, or was the river giving us an unexpected gift, a moment of respite and relaxation in a year of anxiety and fear?

In the U.K. where mudlarking is well-known, the YouTube channels, books and photographs have grown in popularity this past year. On the Thames foreshore, mudlarking as an activity makes sense — the Thames is a tidal river that runs through a city that goes back to Roman times. Water rushes in and out over the banks, exposing and revealing new things daily.

But in Winnipeg, a mid-continental city of rivers, there is no daily tide to wash things in and out of the banks. There is only the slow movement of the seasons that determines the rise and fall of river levels. If the rivers are to reveal anything, they will do so at their own pace, climate change notwithstanding.

There is a time for everything, and a season for every activity under heaven, says Ecclesiastes. In a pandemic year, I’m grateful the rivers of Winnipeg have made this a great season for mudlarking.

— Sally Ito is a Winnipeg writer

.jpg?h=215)