Painting the pandemic Dedication of health-care workers inspires artist

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 11/05/2021 (1387 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

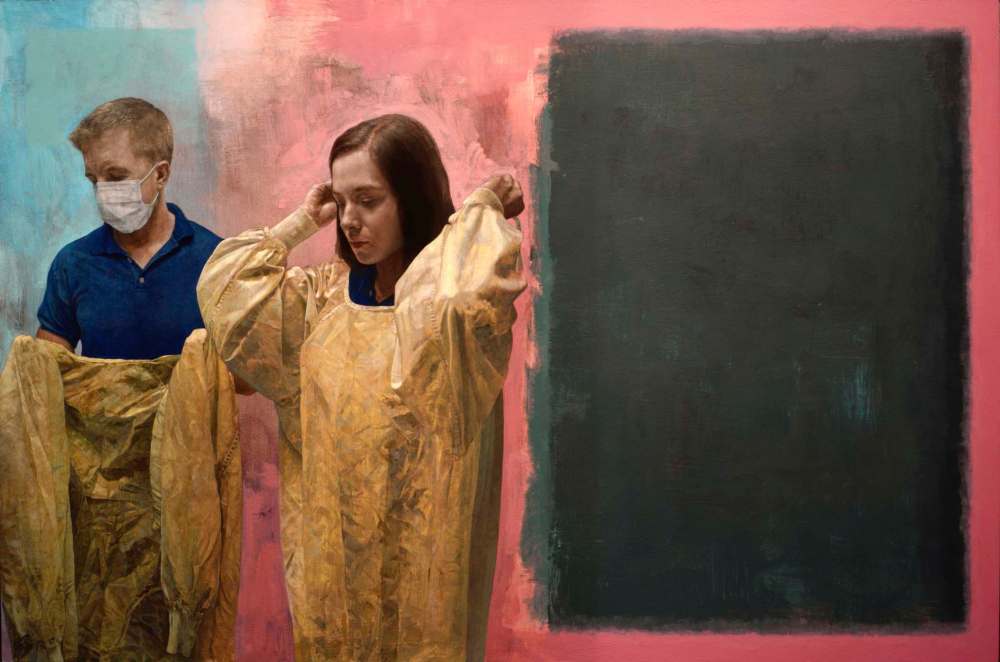

Katrina’s eyes are downcast and her hands are raised behind her head. She looks calm, if not a little tired, while lacing up the strings of her yellow hospital gown — a garment designed to prevent skin-to-skin contact with viral patients and one that has become a common uniform for health-care workers during the pandemic. Her colleague, Justin, stands nearby wearing a surgical mask and preparing to don his own gown. An ominous black rectangle looms large behind them.

The scene is the work of Winnipeg painter Clinton Roberts, who, in addition to being a self-taught fine artist, has been employed in the patient transport department of the Health Sciences Centre for the last 12 years. As the coronavirus spread locally, Roberts, 49, realized he was in a privileged position to document the plight of hospital workers amid the pandemic.

“My whole interest in art has always been about painting people,” he says. “An artist can express so many things about health care with what’s currently happening… I specifically want to bring attention to the people who do health care.”

The painting of Katrina and Justin, who work with Roberts in patient transport, is one piece in his ongoing Pandemic Worker series, which blends high-realism portraits with abstract backgrounds.

Roberts was known as the “art guy” in high school. He took a job at the former Midtown Gallery on Graham Avenue post-graduation and found a valuable mentor in the gallery’s owner, “I was really able to hone my understanding of art and my technique through someone who provided a lot of positive criticism.”

In his early 20s, Roberts was determined to make a career out of his art. He garnered local interest after mounting his first solo show in Winnipeg and moved to England looking for bigger opportunities. He lived and worked in a small cottage in the Sussex countryside that could’ve been plucked from a Van Gogh painting and eventually landed a spot in a contemporary art exhibition at the Belgrave Gallery in London. But he missed the wide open prairies and moved home several years later to escape the bustle and the claustrophobic English weather.

Even though art was his passion, money was a necessity. He traded in his brushes for a graphic design diploma and made the transition to health care after his daughter was born.

“She became my No. 1 priority,” Roberts says. “Doing hospital shift work gave me the best means to care for my daughter and be really involved in her life.”

“An artist can express so many things about health care with what’s currently happening… I specifically want to bring attention to the people who do health care.” – Clinton Roberts

Painting took a backseat for a long time. With his wife’s encouragement, he carved out a small studio in the sunroom of their home — a space that is slightly bigger than a closet and sectioned off by curtains to allow their pet bird to sleep during nighttime painting sessions.

Roberts piqued the interest of colleagues when he started sketching during his breaks at work.

“My co-workers were quite surprised,” he says. “At that point it was very easy to get people to volunteer to become models for an artwork.”

As the pandemic surged and lockdowns went into effect, his co-workers became the only people he could paint.

As a patient transporter, Roberts sees himself as the “eyes and ears” of the hospital. He walks more than 20,000 steps a shift and has contact with every department while moving the sick and injured from one area to another.

“We see a lot of stuff,” he says. “We even transport the deceased to the morgue, so we see the end of health care as well.

“(It) puts me in a very interesting position to capture a reflection of our health-care workers.”

His is one of many health-care jobs invisible to the general public, but essential for keeping a very complex machine running smoothly. While burnt-out intensive care doctors and nurses have garnered most of the media attention, the pandemic has been a challenge for everyone who works in the field.

“Health-care workers are human, they get scared when they know they’re going to be challenged with something that could really harm them,” Roberts says. “And yet, we still have to do our jobs, because that’s what is expected of us.”

Roberts speaks passionately about hospital work and cautiously about the larger political and economic factors affecting his day-to-day job. Newer equipment and more resources would improve working conditions, but those issues are well beyond his pay grade.

“Health-care workers are human, they get scared when they know they’re going to be challenged with something that could really harm them.” – Clinton Roberts

“The responsibility lies closer to the top,” he says. “For everyone at the bottom, we have to try to do our best despite the circumstances and those circumstances aren’t always ideal.”

Instead, he celebrates the people at the bottom with acrylic paint and careful brushstrokes.

So far, Roberts has completed two paintings for his Pandemic Worker series and hopes to feature subjects from a wide range of departments in the future; including housekeepers, lab technicians, nurses and doctors — patients are out of the question thanks to the Personal Health Information Act.

As an artist, he has always combined realism with abstraction and the world of health care lends itself well to the style. In his painting of Katrina and Justin, the large black mass that dominates the frame is a stand-in for COVID-19 and everything it represents.

“It’s a presence, it’s something that you can’t see, but it’s very real,” he says. “With the abstract elements, I can put complex issues regarding health care into a visual that allows someone to have a sense of the feelings of such an environment.”

Roberts works night shifts and paints most afternoons. While many people have picked up hobbies new and old to relieve stress during the pandemic, he sees art as a serious endeavour.

“If I were to just make nice pictures I could, I have the technical skills to paint as good as anyone,” he says. “But if I don’t have much to say with it, I never feel like the art is worth the time.”

Using free time to revisit his workplace has been more than worth it.

“This stuff is important,” Roberts says. “I hope my art can bring attention to the fact that health-care workers are people and… how much value you place on the people that do the job is important.”

Visit clintonrobertsart.com to view more of his Pandemic Worker series.

“I hope my art can bring attention to the fact that health-care workers are people and… how much value you place on the people that do the job is important.” – Clinton Roberts

eva.wasney@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @evawasney

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.