An enduring warmth Welcoming heart of Winnipeg's first Black church beats as strongly now as it has through its 97-year history

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 19/02/2021 (1753 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

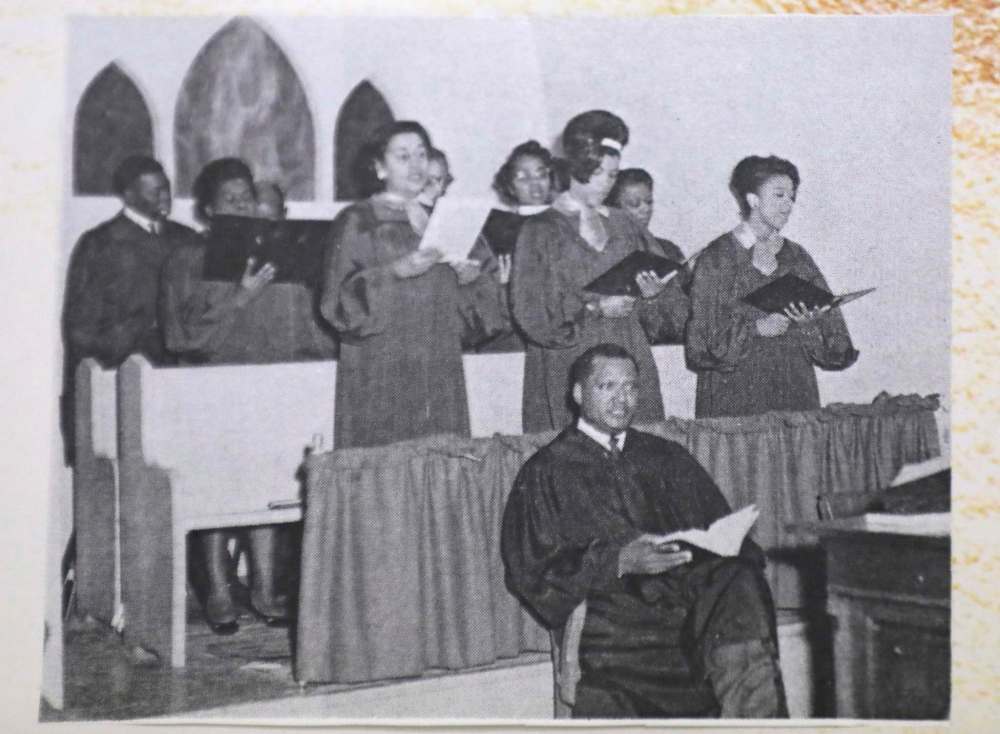

It’s not hard to imagine the sanctuary at Pilgrim Baptist Church in its heyday — pews packed with generations of family members crowded together, a 40-person choir rising up in their red and gold robes, sunlight pouring in from the row of south-facing windows, their voices joining together for Sunday morning’s opening hymn.

Today, things are much quieter. COVID-19 concerns have left the pews empty, but even before the pandemic the choir’s number had dwindled to just 12, the congregation from 150-strong to between 35 and 50 on a good day.

Still, the oldest Black church in Manitoba keeps its history alive — in the pews, within its walls and through time-aged memories.

For Valerie Williams and her husband Bill Thomson, Pilgrim Baptist Church and its Maple Street edifice has been home for decades.

“It was my family’s church,” Williams says on the phone.

She had been a member off and on throughout the years, but settled in for the last 15 or so, she says.

Back in the day, her father Lee Williams was a deacon. His picture — from the 2002 day when he received an honorary doctorate from Toronto’s York University for his human-rights union work on behalf of Black railway porters — is propped up in the church basement. Her mother, Alice, was keenly involved, too.

Thanks to their involvement in the early years, Williams has long carried memories of the church’s storied history. She has recently begun organizing a project to enshrine it for the next generation.

“I’m a member with a real keen interest in Black history and celebrating Black history month,” she says.

Williams organizes the church’s Black History Month events every February, and through the Canadian Heritage Fund has secured federal grants for the last two years.

The church has previously marked the month in small ways — the children would give presentations on well-known Black celebrities, sports stars and activists, Williams says. This year, however, the events are taking place online, and feature panels, speakers, DJs and reflection on the significance of the church in Winnipeg’s early Black history.

Official records of the early church are scarce — a smattering of old newspaper clippings document the congregation’s search for a permanent home and dealing with disasters involving fire and floods. There are also notices listing services times and announcing visiting preachers.

Other pieces of the past line the walls in the basement: along with newspaper articles, there are posters promoting long-ago boxing matches featuring church members, photos of the choir, the congregation, previous iterations of the building, picnics and dinners.

Williams’ husband, Bill Thomson, leads an informal tour, adding anecdotes to the faces and names on the wall. He’s been around the church for about 30 years, he says, brought in by Valerie’s mother. He’s had various roles there over the years — finances, maintenance — whatever he could do to lend a hand.

He loves the place, he says. He loves God, he loves Jesus, but he really loves the Church.

“They got it,” he says of Pilgrim Baptist’s community, of its welcoming values. “They’ve got it.”

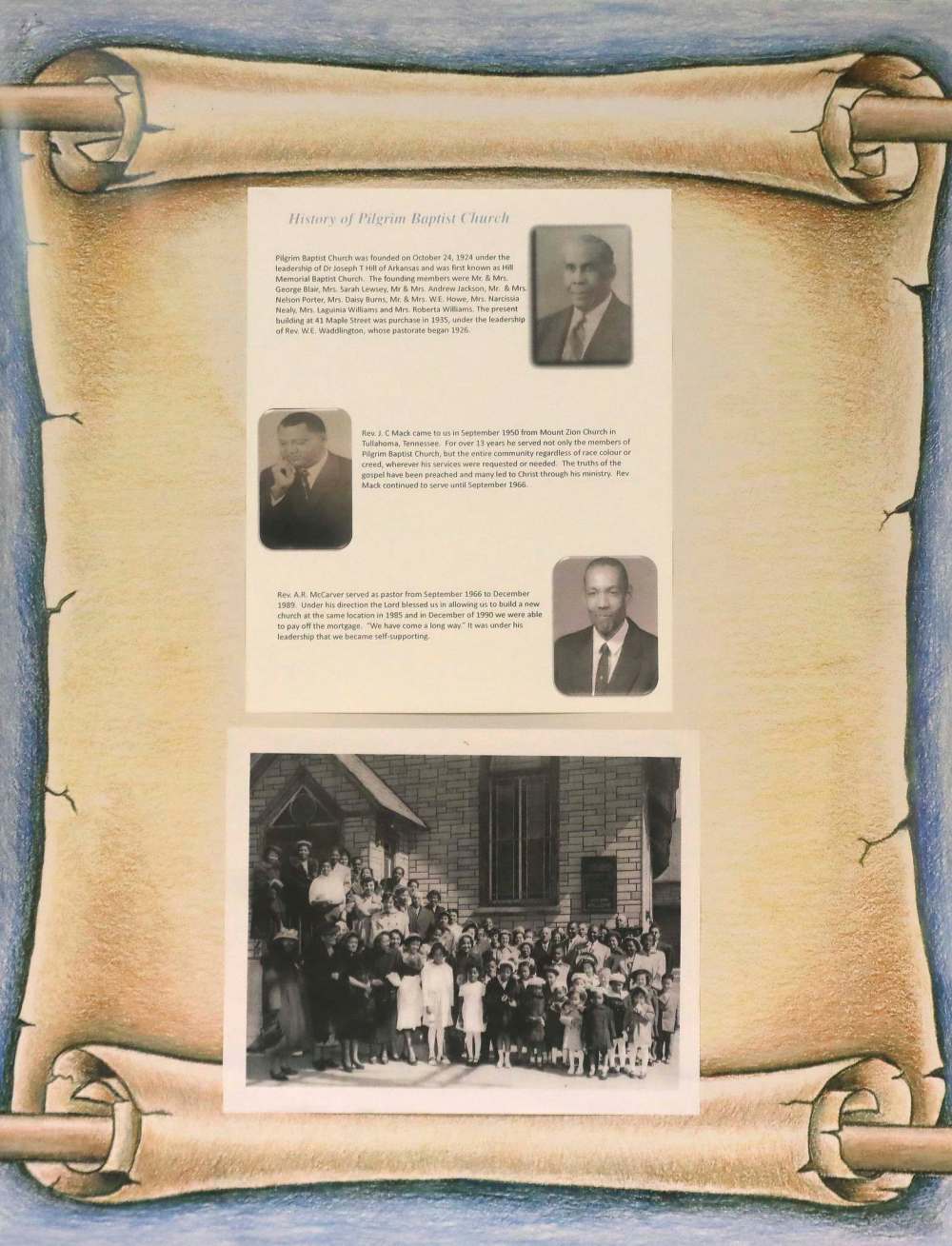

There’s a seven-page document comprised of interviews from early church members (including Lee and Alice Williams), research, newspaper records and commemorative booklets. It is, the document says, “the most comprehensive record of the history of Pilgrim Baptist Church.”

As the story goes, Pilgrim Baptist started as Hill’s Memorial Baptist Church, rising out of a service the visiting Rev. Dr. Joseph T. Hill had been regularly giving at Zion United Church on Pacific Avenue.

Hill, native to Arkansas, founded then-Hill’s Memorial on Oct. 24, 1924 with a congregation of just 13 members. They met in the home of Mr. and Mrs. George Blair, Suite 21 – 123 Sutherland Ave.

University of Winnipeg history professor Paul Lawrie, who specializes in early African American history, says the early Black community in the city would have been largely made up of members such as Hill: travellers from the American South making their way northward in the post-Reconstruction era.

A first wave of migrants would have landed in the industrial North and Midwest, cities such as Chicago, for example. A second wave, he says, was instrumental in North America’s westward expansion.

“You find that smattering of Black settlers that would have found their way into Saskatchewan or Manitoba, whether that be through the railway lines, whether that be through the cattle trail,” he says.

“You find that smattering of Black settlers that would have found their way into Saskatchewan or Manitoba, whether that be through the railway lines, whether that be through the cattle trail,” – U of W history professor Paul Lawrie

Black cowboys, labourers and railway porters would have passed through these industrial towns, stopping for work and creating what Lawrie describes as a “transitory community.”

“We’re not talking about substantial numbers of people,” he adds.

Indeed — in the early 20th century Winnipeg’s Black community was small, just 300 or so people between 1908 and 1915, Williams says.

“A lot of these people were CNR and CPR porters, and the church was built very close to the railway station. That was part of our population of the church… the porters,” she notes.

“When I was young, I can remember pretty much knowing every Black person in Winnipeg. The church was a real hub for the community, and it brought people together. In some respects, for a lot of people, it was a community centre.”

The church moved around in its early years, the record says, from Austin Street to the corner of Alexander Avenue and Stanley Street, then Jarvis Avenue and, finally, 41 Maple St. “an old Point Douglas address that is in the shadow of the CPR station.”

By 1928 the church had taken on the Pilgrim Baptist name, following a congregational vote, and settled into a dusty building in desperate need of repair. The current iteration stands in the same place.

“It was really small, it was pretty old,” says Williams of the early building. “When we got our brand-new building it was just amazing.”

That new building wouldn’t come for decades. Fires and floods would first ravage the old structure, pushing the growing congregation to scrape together building fund after building fund to keep its meeting place upright.

On Jan. 6, 1950, the Winnipeg Tribune reported a fire had decimated the interior of the church, which happened to be across the street from the No. 3 fire hall. The blaze caused $8,000 in damages to a building valued at $15,000.

The fire had been discovered by the church caretaker, Tribune staff wrote, and was believed to have been started by an overheated furnace pipe running near a wooden partition in the basement. It swept to the first floor in just 10 minutes.

With support from the Baptist Union of Western Manitoba, the Red River Valley Association and other churches across the West, the congregation rebuilt.

Much like the Book of Revelations, fire was only the first disaster to strike the church in 1950.

Just months later the Red River spilled over its banks, and much of Winnipeg, including Pilgrim Baptist Church, was swallowed up by the muddy waters.

Once again, the record states, the congregation rose to the challenge, pitching in to “pick up the broken pieces, literally, and to clear away the rubbish.”

Despite the calamities, the church had grown substantially by the 1950s and had begun to take on its role as Winnipeg’s foremost Black church.

According to Lawrie, a post-war need for domestic, medical and manual labour in the 1950s, coupled with a drop in the cost of airfare, encouraged immigrants from the West Indies to move into the Canadian West.

As Winnipeg’s Black community grew, so did the church’s legacy.

“It’s establishing community pretty much out of nothing,” Lawrie says of spaces such as the church.

“It shows the adaptability, the resilience and the malleability of Blackness. It works across borders, it works across space, it’s not just defined or contained in a particular locale.”

There is no documentation of the beginning of the church’s many traditions including the chicken dinner and the spring tea, but they likely began in the late ’40s and early ’50s, Martha Helgerson writes in Pilgrim’s consolidated history on the basement walls.

Williams remembers those traditions fondly: spring teas with fancy sandwiches and silverware, fried chicken dinners bringing the whole neighbourhood to church.

Members recall the congregation being bigger in the summer when American men would travel north for work on the railway lines through the ’50s.

From the 1950s though the 1970s, Williams says, Pilgrim Baptist was “the” Black church in Winnipeg.

“People could identify that this was a place to go. This was a place you were going to find fellowship; even if it wasn’t a religious reason why you went, you went for community, for people that could understand you, relate to you,” she recalls.

Judy Atwell Williams’ family has been rooted in Winnipeg since 1905. Her mother’s family moved to the North End from Minnesota after hearing there were jobs on the railway. Her father immigrated decades later, as a university student from Trinidad in the 1950s.

Her grandfather was a sleeping-car porter and involved in the union. Her grandmother started the very first Black Girl Guides group in the city.

The pair ran boarding houses on Charles and Henry streets.

They were members of the church for a time, later converting back to Roman Catholicism, but continued to support the church for years after they left.

Atwell Williams will talk about the church’s community legacy next week when she speaks at a Pilgrim Baptist Black History Month event.

The church was one of a handful of community spaces where the Black community could gather. There was Hayne’s Chicken Shack, owned by Percy Haynes. There were picnics at Grand Beach — Winnipeg Beach was less friendly to the Black crowd — and later there was Folklorama, as more immigrant groups settled on the Prairies.

But there was always Pilgrim Baptist Church.

“It definitely was known as the hub not just for Black families who lived in the North End or in Winnipeg, but for people who might be travelling through town and needed a place to worship that was safe,” Atwell Williams says.

“I think there are a lot of places that Black people couldn’t go in Winnipeg. To know that you could go somewhere safely with your family or if you were feeling isolated was essential to that feeling of belonging. Everyone needs to feel that feeling of belonging.”

For decades Pilgrim Baptist stood as a beacon, a safe haven for the Black community, transient or established.

In the 1980s the building expanded, and a renovation project spearheaded by Williams’ father saw the church become what it is today. In 1985, the 95-by-50-foot split concrete-block edifice, featuring a tall and sloped roof with east-facing windows pouring light behind the pulpit, was erected.

“I can remember the times the church was full,” she says wistfully.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, the church was bustling, hosting picnics, teas and a full Sunday school, she says. Both the membership and leadership was strong. There were regular events and activities, such as Easter breakfasts and Christmas dinner parties. There was a full-fledged women’s ministry. A school bus would travel around the North End, sometimes East Kildonan, to pick up kids for Sunday school.

“We used to be packed every Sunday,” Thomson says, gesturing at the rows and rows of pews. “Chicken dinners, the tea, pancake breakfast on Father’s Day, the choir, the concerts.”

“Just good times, good fun. It was always good fun,” Williams adds.

“It was really small, it was pretty old. When we got our brand-new building it was just amazing.” – Valerie Williams

Like many churches, over time the membership dwindled. Thomson figures it declined about eight years ago now, maybe more.

“Things have changed for the churches over the years,” Williams says, suggesting it’s the result of a de-emphasis of spirituality in the culture.

Not to mention the church has since fragmented into a half-dozen other Black churches — sister churches, she calls them — such as Truth and Life Worship Centre and New Anointing Church.

There are good relationships between the churches, she says, indeed the history on the basement walls acknowledges the “outstanding” relationship between Pilgrim and the sister congregations.

Williams says Pilgrim Baptist’s welcoming nature hasn’t changed over the years. Like all churches, it has faced challenges, leadership struggles, “certain differences,” and moments of fragmentation are part of its story.

But just as it was a home for Winnipeg’s Black community in its earliest days, it remains so today. “It’s very similar today: we have a place where we belong, we feel welcome, we feel included,” she says.

To celebrate that history this year, Williams has organized a series of Black History Month virtual events under the theme We Can’t Stop Now.

“We have been jailed, murdered, marched and prayed for our equal rights, and today Black people still experience more police shooting deaths, higher jail population, hate crimes, higher unemployment, employment barriers, poor housing, lower wages,” she says passionately.

“So we just can’t stop.”

This year’s celebrations, she says, are happening “in a big way.”

Saturday, from 2 to 4 p.m., the church will host a panel discussion with former Winnipeg Police Services chief Devon Clunis, now Ontario’s Inspector General of Policing, Manitoba Justice lawyer Tanya Brothers, St. Vital NDP MLA Jamie Moses and student and community activist Alexa Joy.

Next Saturday, Judy Atwell Williams will speak alongside Warren Williams and Tynesa Wells in a talk on the early Black history of the West titled “There can be no present or future without recognizing our past.”

Later that evening the church will host a concert over Zoom, featuring Grammy-nominated artist Fresh IE and Nappy.

Despite limited records, the church’s legacy — its history, triumphs, and tragedies — will be sustained, members say. Many of the families that continue as members have been attending for generations; in some cases there are four generations of a family at the church on any given Sunday, Thomson says.

History will be passed down to the next generation in Sunday school classes, its welcoming nature will carry on.

“It’s going to continue,” Thomson says as he locks up the church.

At the end of Helgerson’s history in the church basement is a quote credited to a Mr. and Mrs. E. Criss. It served as a fitting summary then, and remains just as fitting now:

“Pilgrim has had a long and storied history, of laughter and tears, of joy and sorrow, of darkness and light. Yet through all the adversities, the Church still stands, and we are thankful, very thankful.”

julia-simone.rutgers@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @jsrutgers

The Free Press is committed to covering faith in Manitoba. If you appreciate that coverage, help us do more! Your contribution of $10, $25 or more will allow us to deepen our reporting about faith in the province. Thanks! BECOME A FAITH JOURNALISM SUPPORTER

Julia-Simone Rutgers is a climate reporter with a focus on environmental issues in Manitoba. Her position is part of a three-year partnership between the Winnipeg Free Press and The Narwhal, funded by the Winnipeg Foundation.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Saturday, February 20, 2021 12:43 PM CST: Changes through to throughout

The Free Press acknowledges the financial support it receives from members of the city’s faith community, which makes our coverage of religion possible.